Afghanistan debate in Canadian House of Commons : through a glass darkly?

Apr 9th, 2006 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: Countries of the World UPDATE. MONDAY, APRIL 10, 11:30 PM EST. Debates on foreign policy in the parliamentary democratic tradition, the British historian A.J.P. Taylor said long ago, conventionally pit “the stupid party” on the right against “the silly party” on the left. And there were more than a few moments when this evening’s debate on Afghanistan in the Canadian House of Commons tried too hard to live up to the tradition.

UPDATE. MONDAY, APRIL 10, 11:30 PM EST. Debates on foreign policy in the parliamentary democratic tradition, the British historian A.J.P. Taylor said long ago, conventionally pit “the stupid party” on the right against “the silly party” on the left. And there were more than a few moments when this evening’s debate on Afghanistan in the Canadian House of Commons tried too hard to live up to the tradition.

The role of the stupid party was most aggressively taken on by the minority-governing Conservatives. Almost all they could say was that anyone who didn’t just support what the troops in the field were doing regardless was being unpatriotic, and threatening troop morale. The Liberals alas, who started Canada’s current Afghanistan commitment in the first place, largely followed the Conservatives in this case, while trying not to be quite so stupid.

The New Democrats equally took up the part of the silly party with a bit too much enthusiasm. They had one good point. If the new NATO-led mission of the international community in Afghanistan just carries on with the policies of the old US-led coalition that are increasingly obviously not working, then no one’s best interests will be served. But then the NDP almost entirely spoiled this point, with the silly argument that Canadian troops could somehow do the job that even the new NATO-led mission must do, if they just gave up on “war-making.”

The Bloc Quebecois largely weighed in on the NDP side, without trying all that hard not to be quite so silly. The light that may still flicker at the end of the tunnel appears to be that Canada’s federal MPs will continue to study the issue in the months ahead, one way or another. And, perhaps, an opportunity for an actual parliamentary vote on improving things (while still staying quite involved) may arise in connection with renewing the current international commitment that expires in February 2007. Meanwhile, anyone elsewhere in the global village who may be concerned can rest assured that the majority of Canadian MPs stand resolutely behind Canada’s current role in Afghanistan, whatever that may exactly be.

COUNTERWEIGHTS EDITORS’ BACKGROUND REPORT FROM SUNDAY, APRIL 9:

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has decided to go along with a debate on Canada’s current policy in Afghanistan in the just recently returned Canadian House of Commons at Ottawa. It will be held on the evening of Monday, April 10 – scheduled to start at 6:30 PM (EST) and to last no longer than five hours.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has decided to go along with a debate on Canada’s current policy in Afghanistan in the just recently returned Canadian House of Commons at Ottawa. It will be held on the evening of Monday, April 10 – scheduled to start at 6:30 PM (EST) and to last no longer than five hours.

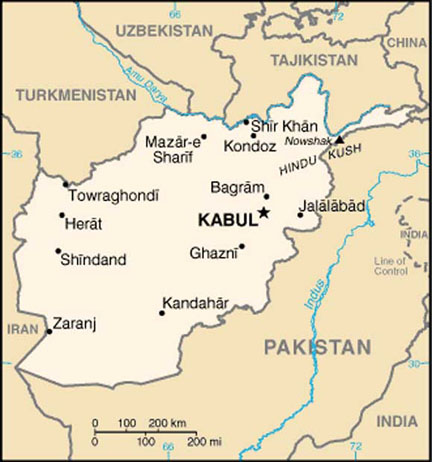

Over the past several days events inside and outside Canada have conspired to set a bit of an interesting stage for this debate. Last Sunday, April 2, e.g., Toronto Sun columnist Eric Margolis – who unusually combines right-wing views with some first-hand knowledge of and sympathy for the opinions of people who actually live in the Middle East – published a provocative piece called “Don’t expect to change the Afghanis.”

This has been followed up, to touch on just three anglophone central Canadian examples, by: Lawrence Martin’s “Are we being taken for a ride?” in the April 6 Globe and Mail; Haroon Siddiqui’s “How, exactly, are troops defending our `national interests’ in Afghanistan and how long will they be there?”in the April 6 Toronto Star; and Curtis Brown’s “Canada’s role in Afghanistan clear at Ground Zero” in the April 8 Brandon Sun.

This has been followed up, to touch on just three anglophone central Canadian examples, by: Lawrence Martin’s “Are we being taken for a ride?” in the April 6 Globe and Mail; Haroon Siddiqui’s “How, exactly, are troops defending our `national interests’ in Afghanistan and how long will they be there?”in the April 6 Toronto Star; and Curtis Brown’s “Canada’s role in Afghanistan clear at Ground Zero” in the April 8 Brandon Sun.

Meanwhile, a new UK House of Commons Defence Committee report has raised what the April 6 TimesOnline described as new “fear for British forces in battle with opium gangs” in Afghanistan. The Times of India for April 8 has reported that Afghanistan President Hamid Karzai will be meeting with Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on Monday, April 10, to “discuss a host of bilateral and regional issues, including the recent spurt in violence in his country, which has killed many American soldiers and Afghans.” And there have been further reports on this “spurt of violence” from, e.g., China, Europe, Turkey, and the United States.

Eric Margolis and his critics and friends …

According to a Globe and Mail report on the Monday, April 10 debate in Ottawa: “Sources say the Tories … believe holding a debate now will inoculate them against future Liberal attacks in the event that the Afghan mission ever becomes an election issue. The debate … will be a take-note’ session only, meaning there will be no vote.”

According to a Globe and Mail report on the Monday, April 10 debate in Ottawa: “Sources say the Tories … believe holding a debate now will inoculate them against future Liberal attacks in the event that the Afghan mission ever becomes an election issue. The debate … will be a take-note’ session only, meaning there will be no vote.”

Eric Margolis’s Toronto Sun column last Sunday, April 2 has already given the MPs’ debate some red meat to chew on. It urges that “it’s important to correct three major falsehoods being promoted by the ill-informed, flag-waving media … 1. Taliban are terrorists’ … 2. Canada is defending “democracy” in Afghanistan’… 3. Canada is defending women’s rights.'”

The most dramatic of this trio is the first. And Mr. Margolis, to say the least, presents a considerably more cheerful assessment of the Taliban than is common in the media of North America and Western Europe (to which should probably be added the mainstream media of Japan and India as well – to make clear that “our side” here is not just the so-called “West” in today’s global village, as convenient a piece of shorthand as that may sometimes seem).

The Taliban, Mr. Margolis says, were originally “not 9/11-style terrorists, but a religious, anti-Communist movement drawn from the Pushtun tribe.” When they first came to power in the wake of the old Soviet Union’s failed intervention in Afghanistan, they “set about fighting banditry, rape and drug dealing, imposing order based on traditional tribal and religious law.”

Margolis concedes that the Taliban’s “backwards leaders” soon “proved themselves to be harsh and incompetent,” but he does urge that they at least “shut down production of opium and heroin.” And “Washington gave millions in aid to the Taliban until four months before 9/11.”

Margolis concedes that the Taliban’s “backwards leaders” soon “proved themselves to be harsh and incompetent,” but he does urge that they at least “shut down production of opium and heroin.” And “Washington gave millions in aid to the Taliban until four months before 9/11.”

Similarly, Margolis stresses that the “Taliban’s leaders knew nothing of 9/11, a plot actually hatched in Germany.” But he does note that: “When the U.S. demanded bin Laden be handed over, the Taliban refused,” because he “was a guest and national hero.”

Following the overthrow of the Taliban by the US-led international coalition that included Canada and many other countries, Mr. Margolis goes on, Taliban activists were “ordered … to blend back into the Pushtun population and wage low-grade guerrilla war against the [new US-led] invaders. Other movements, like Hizbi-Islami, joined in battling foreign occupation.”

This is what Canadian and other “NATO-led” troops are facing fresh surges of now, as they both take over from the US, in some degree, and (rather half-heartedly in some cases) expand military operations in Afghanistan. And in Eric Margolis’s view, the bottom line is just that “Canada unwisely chose to pick a fight with fierce tribesmen whose only desire is to end foreign occupation and be left alone.”

Both Lawrence Martin in the April 6 Globe and Mail and Haroon Siddiqui in the April 6 Toronto Star offer comment and reportage that broadly parallels and supports at least the main thrust of Eric Margolis’s scepticism about Canada’s current involvement in Afghanistan. Curtis Brown in the April 8 Brandon Sun, on the other hand, has just paid a visit to the 9/11 “ground zero” in New York City. And he says that: “Anyone who needs to be reminded why Canadian soldiers are dying in Afghanistan need only stand in the heart of New York’s financial district and peer through the chain-link fence into the gaping hole below.” (And Mr. Brown goes on to add: “Some will say we should have no part in a U.S.-led war on terror’ or be part of America’s imperial war machine.’ That argument may hold up against fighting in Iraq, but does it hold true for 9/11 and our involvement in Afghanistan? Absolutely not.”)

New UK House of Commons Defence Committee report …

It is not just some Canadians who are wondering about the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force’s new challenges in Afghanistan. As the TimesOnline site reported on April 6: “The Commons Defence Committee fears a British-led operation to combat the region’s powerful opium smugglers could lead to a deterioration in security in Helmand province, which British troops are hoping to stabilise … The MPs want ministers and military commanders to detail the precise role the British forces will play in countering the gangs who produce 90 per cent of the world’s opium.”

It is not just some Canadians who are wondering about the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force’s new challenges in Afghanistan. As the TimesOnline site reported on April 6: “The Commons Defence Committee fears a British-led operation to combat the region’s powerful opium smugglers could lead to a deterioration in security in Helmand province, which British troops are hoping to stabilise … The MPs want ministers and military commanders to detail the precise role the British forces will play in countering the gangs who produce 90 per cent of the world’s opium.”

As reported elsewhere on a US site: “A new report from the Commons defence select committee warns that UK forces could come under increased attack from those involved in Afghanistan’s narcotics trade … The defence committee said that the Taliban, now believed to number around 1,000 in the province, were becoming increasingly active in Afghanistan’s narcotics industry.” (An interesting point in connection with Eric Margolis’s stress on how an earlier version of the Taliban in government “shut down production of opium and heroin.”)

Picking up on another theme in the new UK House of Commons Defence Committee report, the UK opposition Conservative Party has also been urging that “Questions remain about Afghanistan deployment … Shadow Defence Secretary Dr Liam Fox has warned that a lack of adequate air cover will expose British troops to unnecessary danger during their forthcoming deployment to Afghanistan.”

The Herald website in the UK also ran an April 6 editorial called “Where’s the Afghanistan plan?” It began with: “What are we doing there? What is the cost? When can we get out? … In the coming weeks, UK forces will assume command of the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) as it extends its sphere of operations into Helmand province a veritable lion’s den.”

The Herald website in the UK also ran an April 6 editorial called “Where’s the Afghanistan plan?” It began with: “What are we doing there? What is the cost? When can we get out? … In the coming weeks, UK forces will assume command of the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) as it extends its sphere of operations into Helmand province a veritable lion’s den.”

It is interesting in this connection as well that, although Canadian troops are apparently headquartered in Kandahar province due east of Helmand, this past week: “Coalition troops, including a contingent of Canadians, marched into” Helmand, “the hub of much of Afghanistan’s illegal narcotics trade, to confront insurgents.”

As the Ottawa Sun further reported on April 8: “The violence in Afghanistan’s poppy-rich Helmand province, where Canadian troops are operating, heightened yesterday with a suicide attack and another friendly-fire incident … A few hours before yesterday’s car bombing, British troops and elements of the Afghan National Police mistakenly battled each other before dawn in southern Helmand province … Each side thought the other consisted of Taliban rebels, said Abdul Rahim Sader, the provincial police chief … The British returned fire and tried to withdraw,’ said Canadian Maj. Scott Lundy in a briefing to reporters at Kandahar airfield, the main coalition base in southern Afghanistan … As they withdrew, they came under more fire’ … Eight police were wounded and an investigation is under way.”

Hamid Karzai’s visit to India …

In his April 6 Globe and Mail column Lawrence Martin noted that Eric Margolis has, among other things, at least “written a book on Afghanistan.” And Martin summarized Margolis’s April 2 column in the Toronto Sun (not a paper that too many Globe readers also read) with: “He says the notion that Canada is defending democracy in Afghanistan is nonsense, that the government there is a U.S.-installed puppet regime, that the elections were rigged, that hundreds of millions have been spent to bribe Afghan warlords … and that there is basically no hope for the Karzai government with its opium-driven economy unless Western troops prop it up – forever.”

In his April 6 Globe and Mail column Lawrence Martin noted that Eric Margolis has, among other things, at least “written a book on Afghanistan.” And Martin summarized Margolis’s April 2 column in the Toronto Sun (not a paper that too many Globe readers also read) with: “He says the notion that Canada is defending democracy in Afghanistan is nonsense, that the government there is a U.S.-installed puppet regime, that the elections were rigged, that hundreds of millions have been spent to bribe Afghan warlords … and that there is basically no hope for the Karzai government with its opium-driven economy unless Western troops prop it up – forever.”

It is a bit interesting in this connection that Afghanistan’s new and always well-dressed President Hamid Karzai will be in the midst of a state visit to India while the Canadian House of Commons debates Canada’s current role in his country on the evening of Monday, April 10. The Times of India notes that the “host of bilateral and regional issues” President Karzai will de discussing with Prime Minister Manmohan Singh includes “Pakistan’s suspected role in providing refuge to the remnants of the Taliban and Al Qaeda … The security for nearly 2,000 Indian workers in Afghanistan – an issue that hogged media headlines when an Indian worker was brutally murdered by the Taliban militia last year – will also come up for discussions.”

India at least has the great virtue of being considerably closer geographically to Afghanistan than Canada (or the US or the UK). And President Karzai has already told the media in India: “Well, we are very happy in Afghanistan to have India helping us in a manner that was not expected. India went out of its way to provide us with great economic assistance. India is among the countries that have given us more than 500m dollars of help. India’s help is actually reaching 600m dollars and it has helped us in all walks of life. These relationships have grown very very well. They are reminding us of the close history and close links that the two countries have with each other and I am sure these relations will grow further and further.”

India at least has the great virtue of being considerably closer geographically to Afghanistan than Canada (or the US or the UK). And President Karzai has already told the media in India: “Well, we are very happy in Afghanistan to have India helping us in a manner that was not expected. India went out of its way to provide us with great economic assistance. India is among the countries that have given us more than 500m dollars of help. India’s help is actually reaching 600m dollars and it has helped us in all walks of life. These relationships have grown very very well. They are reminding us of the close history and close links that the two countries have with each other and I am sure these relations will grow further and further.”

Egypt is another country that is considerably closer geographically to Afghanistan than Canada and so forth. And it is hard not to at least think quickly at first that an Afghanistan international stabilization mission led by, say, India and the Arab League, might have considerably better luck in the enormous task of trying to stabilize a very ancient place with a long history as a turbulent “geographic location at the crossroads of Central, West, and South Asia” than the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Confirmed foreign policy realists will of course point out that this would be altogether practically impossible at the moment, and no doubt this is true. But you still do have to wonder, no doubt as well: Just how much more practically possible is what NATO is going to be trying to do, over the next however long it is?

What is the point of the debate in the Canadian House of Commons on April 10?

Sceptics are equally entitled to doubt just how much point there will finally be to the Afghanistan debate in the Canadian House of Commons on the evening of April 10.

Sceptics are equally entitled to doubt just how much point there will finally be to the Afghanistan debate in the Canadian House of Commons on the evening of April 10.

It is going to be “a take-note’ session only, meaning there will be no vote” – and thus no prospect of any change in current Canadian policy, designed, e.g., to make the job of the Canadian troops everyone is certainly supporting fervently somewhat safer and more achievable.

Moreover, as Haroon Siddiqui has stressed, among at least the two major parties in Parliament today, “there is no appetite for a debate in Ottawa … The Liberals have a vested interest in defending the mission, having quietly committed to a different role in Kandahar than in Kabul. The Conservatives, ideologically predisposed to military operations, have been gung-ho ever since the Prime Minister went to Afghanistan and suggested it was our patriotic duty to shut up.”

Still, whatever you may think about any of it exactly, there is obviously a great deal about this issue that begs to be further and further discussed and watched closely – in Canada and many other countries today, around the global village. The debate on April 10 in Ottawa will at least be a start locally. And that is better than nothing at all.

UPDATE: Meanwhile, according to a Sunday, April 9 CP report : “In a weekend interview with The Canadian Press, insurgent spokesman Qari Yuosaf Ahmedi said the Taliban are convinced the resolve of the Canadian people is weak …

“We think that when we kill enough Canadians they will quit war and return home,’ Mr. Ahmedi said in an interview, conducted through a translator, over a satellite telephone … Given the fact troops are already deployed, Mr. Ahmedi suggested Monday’s House of Commons debate as a sign of indecision among Canadians.”

According to the same report: “And on Sunday, a new poll suggested the public is evenly divided on the Afghan mission … The survey by Decima Research found 45 per cent of respondents considered the deployment a good idea while 46 per cent viewed it as a bad idea. That’s a statistical dead heat, given the poll’s margin of error.”

Mr. Ahmedi – whoever he is exactly – would seem to be right about “indecision by Canadians.” When Monday evening’s parliamentary debate is over and Canadian troops are still in Afghanistan he may have to think again, a little. But he may also feel that the scheduled cuts in US troop strength (as the NATO-led ISAF takes on more responsibility) are a sign that the resolve of the American people is weak as well. The point seems to be: how does the international community show him that his current calculations will not work for him? What has been tried over the past few years does not seem to be doing the trick. What will? If Monday evening’s debate can get Canadians a little closer to that answer, it will also be worthwhile.