Charm Tong’s Burmese days : Orwellian nightmare alive and well in Myanmar

Jun 20th, 2006 | By Randall White | Category: Countries of the World George Orwell (1903-1950) was such an interesting political writer partly because he lived through so many troubling issues of both his and our day in his own life. Reading about the human rights activist Charm Tong’s June 2006 visit to Canada, at least, is likely to make anyone who has read the book remember Orwell’s first published novel, Burmese Days (1934).

George Orwell (1903-1950) was such an interesting political writer partly because he lived through so many troubling issues of both his and our day in his own life. Reading about the human rights activist Charm Tong’s June 2006 visit to Canada, at least, is likely to make anyone who has read the book remember Orwell’s first published novel, Burmese Days (1934).

Ms. Tong was in Toronto “for the annual conference … of the Montreal-based organization Rights & Democracy,” June 14-15. She spoke at the University of Victoria on June 18, and she is appearing at Simon Fraser University on June 22, and at the University of British Columbia’s World Peace Forum on June 23.

Wherever she goes she talks about the grim life among her native Shan minority in present-day Burma. If it was important for democracy to dismantle Saddam Hussein’s oppressive regime in Iraq, it ought to be important to shut down the smoothly ruthless military thugs who have tried to re-name Burma “Myanmar” – a place that already has its own internal democracy movement, which desperately needs help from the outside global village.

The ghost of George Orwell has to be interested in what Charm Tong has to say. And not just because his first novel was called Burmese Days. When he died, in 1950, he was thinking about a project called A Smoking Room Story’ – “planned as a novella of thirty to forty thousand words which told how a fresh-faced young British man was irrevocably changed after living in the humid tropical jungles of colonial Burma.” Orwell himself had spent five years in Burma, aged 19 to 24, and he knew what he was talking about.

Orwell’s Burmese Days in the 1920s …

“George Orwell” is the pen name of an authentic if rebellious child of the now-fallen British empire on which the sun once never dared to set.

“George Orwell” is the pen name of an authentic if rebellious child of the now-fallen British empire on which the sun once never dared to set.

His given name was Eric Blair. And he was born in 1903 in India, where his father, Richard Blair, was a middling employee in the Opium Department of the old British Raj. (Among other things, believe it or not, the legendary Men Who Ruled India were international drug dealers.)

As was the custom in many such families, Orwell returned to England with his mother when he was very young, to be educated in the metropolitan homeland. Through some very hard studying as a very young man (and some pulling by his mother on a few threadbare family strings), he managed to get into the cream of English private schools at Eton on a scholarship.

Once he had made it into Eton, however, the teenage Eric Blair decided to enjoy himself instead of studying. The result was that when he graduated several years later he did not have good enough marks to get into the universities at Oxford and Cambridge on a scholarship. And his “lower-upper-middle class” parents could certainly not afford the fees. So the future George Orwell took a leaf from his father’s book, and joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma.

Once he had made it into Eton, however, the teenage Eric Blair decided to enjoy himself instead of studying. The result was that when he graduated several years later he did not have good enough marks to get into the universities at Oxford and Cambridge on a scholarship. And his “lower-upper-middle class” parents could certainly not afford the fees. So the future George Orwell took a leaf from his father’s book, and joined the Indian Imperial Police in Burma.

(Orwell was making a bow here to his mother, Ida Limouzin, as well. Though born in England, she had grown up in Moulmein, Burma, where her French father was involved in the local teak-lumbering business. And the young Eric Blair still had maternal relatives to visit in Burma, when he went there with the Imperial Police.)

By all accounts, the future George Orwell fulfilled his colonial policeman’s duties in Burma with the expected crisp competence, bred by his family ties and ruling-elite education in England. Yet – perhaps partly drawing on the same rebellious streak that had earlier stimulated his protest of scholarly inertia at Eton – he acquired a profound dislike of what he was doing in Burma.

After his first five-year stint was up Eric Blair resigned from the Imperial Police, in his mid 20s. He returned to England (and, for a time, to his maternal grandfather’s family in France), to start trying to earn a living as a writer. Twenty years later he had become famous enough as George Orwell, the author of the best-selling Animal Farm (1945) – a fable on the sad growth of a totalitarian autocracy, not too unlike the USSR in Soviet Russia.

After his first five-year stint was up Eric Blair resigned from the Imperial Police, in his mid 20s. He returned to England (and, for a time, to his maternal grandfather’s family in France), to start trying to earn a living as a writer. Twenty years later he had become famous enough as George Orwell, the author of the best-selling Animal Farm (1945) – a fable on the sad growth of a totalitarian autocracy, not too unlike the USSR in Soviet Russia.

At the same time, the mature George Orwell who was so opposed to the political theory and practice of Soviet communism was a self-confessed “democratic Socialist.” And he also ardently opposed carrying on with the anti-democratic project of the British empire.

Orwell’s case against the empire was first set out, fictionally as it were, in his first published novel of 1934, Burmese Days. But it was summarized in a much shorter space in one of his subsequent celebrated essays, called Shooting an Elephant.’ Here he returned to his unsettling experience in Burma (19221927), during his early 20s:

Orwell’s case against the empire was first set out, fictionally as it were, in his first published novel of 1934, Burmese Days. But it was summarized in a much shorter space in one of his subsequent celebrated essays, called Shooting an Elephant.’ Here he returned to his unsettling experience in Burma (19221927), during his early 20s:

“I had already made up my mind that imperialism was an evil thing and the sooner I chucked up my job and got out of it the better. Theoretically – and secretly of course – I was all for the Burmese and all against their oppressors, the British. As for the job I was doing, I hated it more bitterly than I can perhaps make clear. In a job like that you see the dirty work of Empire at close quarters. The wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of the lock-ups, the gray, cowed faces of the long-term convicts, the scarred buttocks of the men who had been bogged with bamboos – all these oppressed me with an intolerable sense of guilt.”

Charm Tong’s new Burmese Days 2006 …

One of the almost happy great political ironies of the 20th century is the story of how the long regime of the British Raj, in the midst of its guilt-ridden “dirty work of Empire,” at least helped inspire a functioning new democracy in the independent Republic of India – which officially proclaimed itself in 1950, the year George Orwell died. Yet just as the parallel case of Pakistan would move in much less democratic directions, the end of the shorter-lived British imperial regime in neighboring Burma did not work out so well.

One of the almost happy great political ironies of the 20th century is the story of how the long regime of the British Raj, in the midst of its guilt-ridden “dirty work of Empire,” at least helped inspire a functioning new democracy in the independent Republic of India – which officially proclaimed itself in 1950, the year George Orwell died. Yet just as the parallel case of Pakistan would move in much less democratic directions, the end of the shorter-lived British imperial regime in neighboring Burma did not work out so well.

(You might deduce a deeper proposition from the sadder experiences of Burma, Pakistan, and perhaps Sri Lanka too. India’s own remarkably diverse and very ancient traditions have probably been more decisive in the success of its present-day world’s largest democracy than the half-progressive side of the old British empire. Or, as Amartya Sen has lately pointed out: “democracy is intimately connected with public discussion and interactive reasoning. Traditions of public discussion exist across the world, not just in the West.” And India today does apparently have still strong ancient traditions of just this sort.)

As George Orwell learned first hand, the people of Burma were especially unimpressed by the British Raj. After Orwell’s friends in the homeland UK Labour Party were voted into office at the end of the Second World War, Burma joined Ireland in the vanguard of the democratic post-colonial dismantling of the old greatest empire since Rome.

As George Orwell learned first hand, the people of Burma were especially unimpressed by the British Raj. After Orwell’s friends in the homeland UK Labour Party were voted into office at the end of the Second World War, Burma joined Ireland in the vanguard of the democratic post-colonial dismantling of the old greatest empire since Rome.

Burma officially became an independent republic in 1948. But even before this there were signs of trouble ahead, when “nationalist leader, General Aung San, whose resistance to British colonial rule culminated in Burma’s independence” was assassinated in 1947. (The same thing happened to Gandhi in India, but not to Nehru, who was politically more important in the end. And neither Gandhi nor Nehru were military leaders.)

For at least its first decade and a half, the new independent republic of Burma did operate more or less as a parliamentary democracy, on essentially the same old British “Westminster model” as India. It even gave the global village U Thant, who served as a successful enough Secretary General of the United Nations 19611971.

Unlike India, however, the new independent Burma did not effectively embrace a federal system of democratic government, to accommodate its fractious regionally based ethnic and religious minorities, alongside the Burman Buddhist majority. Burma from 1948 to 1962 finally wound up like Central Europe when Germany tried democracy … 1918 to 1933. Shortly after U Thant became UN Secretary General late in 1961, back in his home country General Ne Win staged a military coup in 1962, and launched “his idiosyncratic Burmese Way to Socialism’.”

Burmese democracy did not vanish after 1962. It continued to boil and bubble beneath the surface of Ne Win’s authoritarian military regime. It even tried valiantly to stage a comeback in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Ne Win resigned in July 1988, and this “triggered a remarkable series of events, including … pro-democracy protests, the re-assumption of power by Ne Win loyalists in the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), ethnic mutinies … and, finally, the victory of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in the 1990 general election, along with 19 ethnic minority parties that also won seats.”

Burmese democracy did not vanish after 1962. It continued to boil and bubble beneath the surface of Ne Win’s authoritarian military regime. It even tried valiantly to stage a comeback in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Ne Win resigned in July 1988, and this “triggered a remarkable series of events, including … pro-democracy protests, the re-assumption of power by Ne Win loyalists in the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), ethnic mutinies … and, finally, the victory of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in the 1990 general election, along with 19 ethnic minority parties that also won seats.”

The leader of the National League for Democracy, and ultimate winner of 82% of the parliamentary seats in the 1990 election, was Aung San Suu Kyi, “the daughter of the late Burmese nationalist leader, General Aung San, whose resistance to British colonial rule culminated in Burma’s independence in 1948.” But the SLORC military regime that still gripped the country (albeit in the face of recurrent minority ethnic mutinies and insurgencies) refused to recognize the results of the election. It confined Aung San Suu Kyi to a house arrest, in which she has, with intermittent exceptions of various lengths, remained to this day.

The SLORC military regime in Burma that succeeded Ne Win in 1988, and put Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest after her dramatic 1990 election victory, remains in power in 2006. But in a nice example of Orwellian “double speak,” it has cleverly changed its official name to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). Following similar linguistic practices prophesied in George Orwell’s last book on the prospects of a continuing global totalitarian nightmare, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1948), the current military rulers of Burma have also tried to change their country’s official name – in English at least.

The SLORC military regime in Burma that succeeded Ne Win in 1988, and put Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest after her dramatic 1990 election victory, remains in power in 2006. But in a nice example of Orwellian “double speak,” it has cleverly changed its official name to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). Following similar linguistic practices prophesied in George Orwell’s last book on the prospects of a continuing global totalitarian nightmare, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1948), the current military rulers of Burma have also tried to change their country’s official name – in English at least.

(As explained on the Wikipedia site: “In 1989, the military junta officially changed the English version of its name from Burma to Myanmar … The renaming proved to be politically controversial, seen by some as being less inclusive of minorities, and linguistically unscholarly. Some disagree that the military junta had authority to officially’ change the name in English in the first place. Acceptance of the name change in the English-speaking world has been slow, with many people still using the name Burma to refer to the country.”)

The continuing good news is that Aung San Suu Kyi’s Burmese democracy movement is also still struggling to keep its head above water. And that finally explains Charm Tong’s visit to Canada in June 2006. In Toronto she was accompanied by “Sein Win, prime minister for the Myanmar government-in-exile.” Win “is a cousin of the heroic Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel laureate who led the country’s democracy party to a landslide victory in 1990 … but who has languished under house arrest for more than 10 of the past 17 years.” He was “asking Canada and the international community” to help restore democracy in Burma today.

The continuing good news is that Aung San Suu Kyi’s Burmese democracy movement is also still struggling to keep its head above water. And that finally explains Charm Tong’s visit to Canada in June 2006. In Toronto she was accompanied by “Sein Win, prime minister for the Myanmar government-in-exile.” Win “is a cousin of the heroic Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel laureate who led the country’s democracy party to a landslide victory in 1990 … but who has languished under house arrest for more than 10 of the past 17 years.” He was “asking Canada and the international community” to help restore democracy in Burma today.

Ms. Tong herself is from the Shan minority in Burma, and now about the same age as George Orwell when he resigned from the Imperial Police in 1927. Her message has its own sharp early 21st century edges. She focuses on the harsh sexual abuses that the military junta of the State Peace and Development Council systematically perpetrate against Shan and other minority women in Burma today. “The regime wants to use rape and sexual violence to control and demoralize the local community,” Ms. Tong says: “By targeting women, they make the community feel ashamed.”

Charm Tong notes as well that an estimated half-million people are hiding from the Myanmar army in the jungle at the moment, and a million or more are said to have fled to nearby countries. (Ms. Tong herself lives in Thailand.) The army has also lately renewed assaults on the Karen ethnic minority, some 50,000 of whom are reported to have fled across the border in recent months. Hundreds of Karen refugees are expected to arrive in Canada this year. “Canada and the international community,” Ms. Tong urges, “should not tolerate this regime any more.”

It is virtually impossible for foreign journalists and writers to get into Burma/Myanmar nowadays. But some visitors try to do work of this sort surreptitiously, while pretending to more general tourism interests. One case in point is the pseudonymous Emma Larkin, author of Finding George Orwell in Burma (2004).

According to Ms. Larkin: “In Burma there is a joke that Orwell wrote not just one novel about the country, but three: a trilogy comprised of Burmese Days, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.” The first book tells the story of Burma’s dysfunctional colonial past under the British empire. The second can be read with indirect reference to the military dictator Ne Win, who “sealed off the country from the outside world … launched The Burmese Way to Socialism,’ and turned Burma into one of the poorest countries in Asia.” And then: “Finally, in Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell’s description of a horrifying and soulless dystopia paints a chillingly accurate picture of Burma today, a country ruled by one of the world’s most brutal and tenacious dictatorships.”

According to Ms. Larkin: “In Burma there is a joke that Orwell wrote not just one novel about the country, but three: a trilogy comprised of Burmese Days, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.” The first book tells the story of Burma’s dysfunctional colonial past under the British empire. The second can be read with indirect reference to the military dictator Ne Win, who “sealed off the country from the outside world … launched The Burmese Way to Socialism,’ and turned Burma into one of the poorest countries in Asia.” And then: “Finally, in Nineteen Eighty-Four Orwell’s description of a horrifying and soulless dystopia paints a chillingly accurate picture of Burma today, a country ruled by one of the world’s most brutal and tenacious dictatorships.”

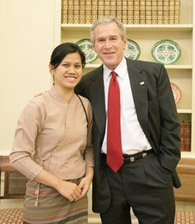

Whatever else, it is hard not to think, again, that if standing up for democracy everywhere means Saddam Hussein’s oppressive regime in Iraq had to be overthrown, at some point some great global democrat also ought to be overthrowing the State Peace and Development Council in Burma, or Myanmar, or whatever the right English name of the country is supposed to be. As it happens, Charm Tong actually paid a visit to George W. Bush last November 2005 – and to Tony Blair in George Orwell’s old imperial metropolis in April 2006. It would seem, however, that there is just not enough oil (or “Islamist terrorists”?) in that part of the world today.

Randall White is the author of a number of books, including Global Spin: Probing the Globalization Debate, and, with the artist Michael J. Seward, On the Road in the GTA: An eclectic guide to the exurban sprawl of Greater Toronto.