David Thompson’s Canadian West & east & the Métis middle ground today

Dec 24th, 2007 | By C. M. W. Marcel | Category: Heritage Now Among many other things, 2007 has been remarkable as the starting year for the “North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative.” But if you missed all this, don’t worry. It will ultimately stretch to 2011, to commemorate “significant events” in the life of a still too little-known new-world geographer “between 1807 and 1811.”

Among many other things, 2007 has been remarkable as the starting year for the “North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative.” But if you missed all this, don’t worry. It will ultimately stretch to 2011, to commemorate “significant events” in the life of a still too little-known new-world geographer “between 1807 and 1811.”

The particular history marked by these dates happened out west, especially in Alberta, BC, Washington (State), and Oregon. But David Thompson also spent the last half of his 87 years back east, in what are now Ontario and Quebec. This past summer’s commerorations included a re-enactment of his “1837 exploration from the east shore of Georgian Bay … through the Muskoka Lakes water system to the Ottawa river.”

In the early 21st century Thompson’s most striking adventure may even be his 58-year marriage to Charlotte Small – a Cree and Scottish girl from the Hudson Bay hinterland, with whom “Koo Koo Sint, the man who gazes at stars’,” cultivated a personal mixed-race cultural Middle Ground that ought to have some provocative relevance for Canada today.

1. David Thompson and Daniel Boone

It is at least somewhat revealing to briefly compare David Thompson with the US frontier icon Daniel Boone – whose 18th and 19th century North American career has just received special attention in no less weighty a place than the New York Review of Books.

It is at least somewhat revealing to briefly compare David Thompson with the US frontier icon Daniel Boone – whose 18th and 19th century North American career has just received special attention in no less weighty a place than the New York Review of Books.

Boone comes from an earlier era than Thompson, but both men lived unusually long lives for their times and places. Boone was born in 1734 and died in 1820, at 85. Thompson was born in 1770 and died in1857, at 87. Similarly, if Daniel Boone epitomizes a key current in the early American experience (with special reference to Pennsylvania, North Carolina, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri), David Thompson reflects a related but rather different scene up north, in the rugged and more inhospitable Canadian geography (east and west).

Daniel Boone’s grandfather had come from England to America in 1717. But Daniel was born near Reading, Pennsylvania. David Thompson was born in England (of Welsh parents), and then recruited from the Grey Coat School in London – a charitable institution for poor boys – for service with the fur-trading Hudson’s Bay Company in northern North America. He arrived at the bleak outpost of Churchill Factory on the forbidding shores of Hudson Bay in September 1784, a year after the end of the American War of Independence, when he was just 14 years old.

Daniel Boone’s grandfather had come from England to America in 1717. But Daniel was born near Reading, Pennsylvania. David Thompson was born in England (of Welsh parents), and then recruited from the Grey Coat School in London – a charitable institution for poor boys – for service with the fur-trading Hudson’s Bay Company in northern North America. He arrived at the bleak outpost of Churchill Factory on the forbidding shores of Hudson Bay in September 1784, a year after the end of the American War of Independence, when he was just 14 years old.

Both Daniel Boone and David Thompson spent time as North American fur traders and frontier surveyors. But Thompson had a more formal education. Boone, as Madison Smartt Bell explains in the December 20, 2007 New York Review of Books, “had no interest in paperwork or other technical requirements.” The Grey Coat School graduate Thompson – a “Mathematical Boy,” as the Washington State author Jack Nisbett has put it – was fascinated by such things, as his copious surviving journals attest (to say nothing of his great map of the Canadian Northwest).

2. Thompson’s career in North America

While recovering from a broken leg in his late teens, David Thompson studied surveying and mapmaking (and astronomy) with Philip Turnor, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s official surveyor.

While recovering from a broken leg in his late teens, David Thompson studied surveying and mapmaking (and astronomy) with Philip Turnor, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s official surveyor.

Thompson had some opportunity to employ his resulting new skills as he continued to work with the HBC. And he became especially interested in mapping the vast new northern and western North American geography that the Company’s fur trading from Hudson Bay, with the Cree and other local aboriginal peoples, had begun to draw into the early world economy.

The main business of the Hudson’s Bay Company, however, was fur trading for immediate profit, not map making for an unknown new longer term future. In 1797 Thompson moved to the rival North West Company, headquartered in Montreal on the St. Lawrence River.

The much newer and more footloose NWC was no less interested in immediate Indian-European fur trade profits. But its partners also had a special need “to locate and map their posts and the waterways connecting them“- with particular reference to the division of western territory between the new United States and the remaining colonial British North America, in the far north pioneered by both the HBC and the “French and Indians” in the 17th and earlier 18th centuries.

The much newer and more footloose NWC was no less interested in immediate Indian-European fur trade profits. But its partners also had a special need “to locate and map their posts and the waterways connecting them“- with particular reference to the division of western territory between the new United States and the remaining colonial British North America, in the far north pioneered by both the HBC and the “French and Indians” in the 17th and earlier 18th centuries.

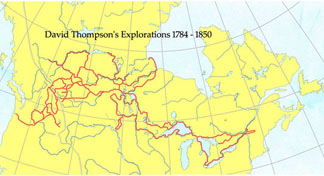

By the time of his marriage to Charlotte Small “according to the customs of the Cree,” in June 1799, Thompson had completed most of his original assignment for the North West Company. This included “the first accurate delineation of those parts of the West most affected by the expansion of American authority under the terms of Jay’s Treaty [between the US and UK, 1794] – the upper Red River valley, the Mandan villages on the Missouri River, the sources of the Mississippi River, and the Fond du Lac and Rainy River regions west of Lake Superior.”

Following his original assignment, the North West Company gave Thompson “additional duty as a trader and for the next seven years he pursued his surveys whenever his other responsibilities permitted,” as he rose from clerk to partner. During this period he completed mapping the northwestern North American fur-trading territories east of the Rocky Mountains.

In 1806 the NWC sent Thompson on a fresh enterprise to open a fur trade with the Indians west of the Rockies. His first outpost in what is now the Canadian province of British Columbia, Kootenay House near the headwaters of the Columbia River, was established in 1807. After many further adventures (at least some of which included his wife Charlotte and a growing family) by the middle of July 1811 he had reached the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Ocean – on the boundary between the present US states of Washington and Oregon.

In 1806 the NWC sent Thompson on a fresh enterprise to open a fur trade with the Indians west of the Rockies. His first outpost in what is now the Canadian province of British Columbia, Kootenay House near the headwaters of the Columbia River, was established in 1807. After many further adventures (at least some of which included his wife Charlotte and a growing family) by the middle of July 1811 he had reached the mouth of the Columbia River on the Pacific Ocean – on the boundary between the present US states of Washington and Oregon.

In 1812 Thompson turned 42 years old. (Charlotte, a mere 13 when he married her, was now in her mid 20s.) The life of even a map-making fur trader in what Thompson himself was already calling the “North-West Territory of the Province of Canada” was arduous even for a very young man. Thompson decided to retire with his wife and family to the Province of Canada proper back east – or at the time, the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada: the (respectively) predominantly English and predominantly French forerunners of modern Ontario and Quebec.

By the end of 1812 David Thompson and his family were re-established in the village of Terrebonne, 30 miles northeast of Montreal. His one remaining task for the Montreal fur trade would be the completion of a “Map of the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada From actual Survey during the years 1792 to1812 … made for the North West Company in 1813 and 1814 and delivered to The Honourable William McGillivray then Agent,” and embracing “the Region lying between 45 and 60 degrees North Latitude and 84 and 124 degrees west Longitude … by David Thompson Astronomer and Surveyor.”

The last half of David Thompson’s life was less obviously and certainly less strenuously adventurous than the first half. And in his lifetime he never became the icon of the frontier spirit in Canada that Daniel Boone had become even before his death in the United States.

The last half of David Thompson’s life was less obviously and certainly less strenuously adventurous than the first half. And in his lifetime he never became the icon of the frontier spirit in Canada that Daniel Boone had become even before his death in the United States.

Yet, although very successful at their careers in some respects, both Boone and Thompson would finally die penniless. And both men were dependent on the adult children of their large families for support in their later years. (Daniel Boone and his wife Rebecca had 10 children. David and Charlotte Thompson had 13.)

But both men also lived as long as they did, it would appear, because they managed to enjoy at least some parts of their old age. “In his mid-eighties,” we are told, Daniel Boone “hunted and walked the woods as much as his failing faculties permitted, and oversaw the carpentry of his own coffin.” The elder David Thompson “read the newspapers and his Bible .. Charlotte was his steady companion, and the two would often stay out most of the night observing the stars.”

3. David Thompson, 1807-1811, and Harold Innis’s Fur Trade in Canada

The “North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative” 2007-2011 has, it seems clear enough, been masterminded in the first instance by the Canadian federal government organization Parks Canada – “as a vehicle for revitalizing interest in Canadian history and appreciation for our country-wide system of National Historic Sites.” More broadly, however, it “has been organized by a not-for-profit partnership of a growing international group of interests who want to commemorate the character and accomplishments of David Thompson … in Canada, the United States and Great Britain.”

The “North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative” 2007-2011 has, it seems clear enough, been masterminded in the first instance by the Canadian federal government organization Parks Canada – “as a vehicle for revitalizing interest in Canadian history and appreciation for our country-wide system of National Historic Sites.” More broadly, however, it “has been organized by a not-for-profit partnership of a growing international group of interests who want to commemorate the character and accomplishments of David Thompson … in Canada, the United States and Great Britain.”

One problem with this admirable international ecumenism, on a strictly Canadian view, is that it somewhat obscures the significance of the events in David Thompson’s life between 1807 and 1811 that are ostensibly being celebrated. From this present-day international angle, what unifies Thompson’s life during this time period is his exploration and mapping of the Columbia River – which starts in southeastern British Columbia, and then finally runs into the Pacific Ocean on the border between the states of Washington and Oregon. And various people in all of Canada, the United States, and Great Britain today can find all this interesting enough.

Yet, again on a more strictly Canadian view, what finally lends David Thompson’s life between 1807 and 1811 its deepest significance is the role he played in the creation of the modern Canadian confederation, which stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans (and the Arctic Ocean too, of course, but Thompson played no direct part in that). And the best starting point for appreciating all this is almost certainly still Harold Innis’s northern North American classic of 1930, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History (which also probably remains the single most interesting and even best book about the history of Canada still extant – and still in print, after more than 75 years).

Yet, again on a more strictly Canadian view, what finally lends David Thompson’s life between 1807 and 1811 its deepest significance is the role he played in the creation of the modern Canadian confederation, which stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans (and the Arctic Ocean too, of course, but Thompson played no direct part in that). And the best starting point for appreciating all this is almost certainly still Harold Innis’s northern North American classic of 1930, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History (which also probably remains the single most interesting and even best book about the history of Canada still extant – and still in print, after more than 75 years).

To start with, e.g., it was the (Montreal-headquartered) North West Company that sent David Thompson to open up new fur-trading territory west of the Rocky Mountains in 1806 – and for whom Thompson established Kootenay House at the headwaters of the Columbia River in 1807, and so forth. And the NWC was a new organization of the 1770s and 1780s, through which British and Anglo-American merchants took over the old French and Indian northwestern fur trade out of Montreal that had traditionally rivaled the Hudson’s Bay Company, based on the shores of Hudson Bay and headquartered back in London, England.

From here Harold Innis stresses two particular features of the North West Company. The first is that it was “the first organization to operate on a continental scale in North America.” By the middle of the 18th century, that is to say, the old French and Indian trade out of the Atlantic Ocean seaport of Montreal (on the St. Lawrence River) had at least vaguely approached the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. By the early 19th century the NWC’s British and Anglo-American takeover of this trade (following the French and Indian and American Revolutionary wars) had reached all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

From here Harold Innis stresses two particular features of the North West Company. The first is that it was “the first organization to operate on a continental scale in North America.” By the middle of the 18th century, that is to say, the old French and Indian trade out of the Atlantic Ocean seaport of Montreal (on the St. Lawrence River) had at least vaguely approached the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. By the early 19th century the NWC’s British and Anglo-American takeover of this trade (following the French and Indian and American Revolutionary wars) had reached all the way to the Pacific Ocean.

And so Innis also stresses that: “By 1821 the Northwest Company had built up an organization which extended from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The foundations of the present Dominion of Canada had been securely laid. The boundaries of the trade were changed slightly in later periods but primarily the territory over which the Northwest Company had organized its trade was the territory which later became the Dominion … The Northwest Company was the forerunner of confederation and it was built on the work of the French voyageur, the contributions of the Indian, especially the canoe, Indian corn, and pemmican, and the organizing ability of Anglo-American merchants.”

Finally, it is helpful to quote Innis on David Thompson’s own particular role in all this, between 1807 and 1811: “There remained to be organized the territory of the Pacific coast drainage basin … In 1805 Simon Fraser was sent to establish Fort McLeod … In 1808 Fraser descended the river which bears his name … In 1806 David Thompson was sent to establish posts across the Rocky Mountains … and in 1807 [he] built “Kootenae House” … Under his direction a post was built at the falls on Kootenay River in 1808. In 1809 Kullyspell House was built and Saleesh House … on Clark’s Fork River. In 1810 because of difficulties with the Piegan Indians he [Thompson] was obliged to cross the mountains by going to the north on Athabasca River. Spokane House was built … In 1811 he went down the Columbia River” to the Pacific Ocean.

Finally, it is helpful to quote Innis on David Thompson’s own particular role in all this, between 1807 and 1811: “There remained to be organized the territory of the Pacific coast drainage basin … In 1805 Simon Fraser was sent to establish Fort McLeod … In 1808 Fraser descended the river which bears his name … In 1806 David Thompson was sent to establish posts across the Rocky Mountains … and in 1807 [he] built “Kootenae House” … Under his direction a post was built at the falls on Kootenay River in 1808. In 1809 Kullyspell House was built and Saleesh House … on Clark’s Fork River. In 1810 because of difficulties with the Piegan Indians he [Thompson] was obliged to cross the mountains by going to the north on Athabasca River. Spokane House was built … In 1811 he went down the Columbia River” to the Pacific Ocean.

In this same context one might also say that David Thompson’s pioneering work of 1807-1811 began the modern history of the most westerly parts of present-day Western Canada, in Alberta and especially in British Columbia. (And there may be something peculiarly appropriate about stressing all this a year or so after Stephen Harper’s new Conservative Party of Canada is said to have at last brought especially this far western part of the Canadian West into power in the federal capital city in Ottawa at last – setting aside the somewhat ambiguous cases of the earlier western prime ministers, John Diefenbaker and R.B. Bennett).

4. D’Arcy Jenish on the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada, 1807-1811

The present-day Canadian hockey historian D’Arcy Jenish’s excellent 2003 biography, Epic Wanderer: David Thompson and the Mapping of the Canadian West, pursues similar themes to those of Harold Innis, from a somewhat different angle again. Jenish stresses how Thompson’s “Map of the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada” was a great achievement, but also “more than mere representation. There was an idea embedded in the map … in the title: the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada.”

The present-day Canadian hockey historian D’Arcy Jenish’s excellent 2003 biography, Epic Wanderer: David Thompson and the Mapping of the Canadian West, pursues similar themes to those of Harold Innis, from a somewhat different angle again. Jenish stresses how Thompson’s “Map of the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada” was a great achievement, but also “more than mere representation. There was an idea embedded in the map … in the title: the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada.”

“Thompson,” Jenish goes on, “created his map between 1812 and 1814. At the time, the Province of Canada extended as far as Lake Superior … In reality the province was sparsely populated and settlement had hardly advanced beyond the shores of Lakes Ontario and Erie. There was no north-west territory. The lands that stretched from Superior to Hudson Bay and west to the Pacific were subject to a patchwork of claims: those of the aboriginal inhabitants, the Hudson’s Bay Co., the North West Co., America and Russia. Nobody, save for David Thompson, saw them as part of the Province of Canada.”

As nicely as this rhetoric may fit so much provincialist ideological rhetoric in Canada today, it can hardly have been altogether true when David Thompson was drafting his great map between 1812 and 1814. (Also the dates of the War of 1812-1814, by the way, in which the new United States tried to invade Canada, unsuccessfully in the end, and take it away from the British Empire, much as it eventually would take both Texas and California away from Mexico).

As nicely as this rhetoric may fit so much provincialist ideological rhetoric in Canada today, it can hardly have been altogether true when David Thompson was drafting his great map between 1812 and 1814. (Also the dates of the War of 1812-1814, by the way, in which the new United States tried to invade Canada, unsuccessfully in the end, and take it away from the British Empire, much as it eventually would take both Texas and California away from Mexico).

Otherwise, David Thompson would not have come up with the title that he did. (He was not quite that original or innovative a thinker.) And then too, already, in 1793, Thompson’s earlier North West Company colleague, Alexander Mackenzie, had written “From Canada By Land” on a rock at the edge of the Pacific Ocean.

There is nonetheless more than a little truth in Jenish’s ultimate conclusion that: “Thompson’s vision of a Canada stretching from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to the shores of the Pacific was half a century ahead of its time. It had no appeal to his colonial contemporaries, but a similar dream resided at the heart of Confederation” in 1867.

It is one of Harold Innis’s continuing virtues to have pointed out that this transcontinental image of the 1867 confederation did in fact have considerably deeper historical roots. (The French Canadians, e.g., had seen the Rocky Mountains by the middle of the 18th century, accompanied by their more easterly Indian allies, and “Canada” itself was an Iroquoian word. On his final Columbia River trip to the Pacific in 1811 David Thompson himself had been accompanied by nine men – five French Canadians, two Iroquois from back east, and two Salish-speaking Sanpoil interpreters from the Pacific Northwest.)

It is one of Harold Innis’s continuing virtues to have pointed out that this transcontinental image of the 1867 confederation did in fact have considerably deeper historical roots. (The French Canadians, e.g., had seen the Rocky Mountains by the middle of the 18th century, accompanied by their more easterly Indian allies, and “Canada” itself was an Iroquoian word. On his final Columbia River trip to the Pacific in 1811 David Thompson himself had been accompanied by nine men – five French Canadians, two Iroquois from back east, and two Salish-speaking Sanpoil interpreters from the Pacific Northwest.)

But it is no doubt equally true that it has taken many years for the depth of these roots to even begin to sink in among the modern Canadian public in all its old and new diversity, aboriginal, francophone, anglophone, and allophone alike.

And (again, on a more strictly Canadian view, at any rate) that is perhaps the very best argument for any kind of ongoing enthusiasm about the “North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative” 2007-2011 – in Western Canada or anywhere else.

5. Back East: the Muskoka region and the Canadian Rebellions, 1837

It probably says something about the subtle differences between the United States and Canada, even today, that Daniel Boone started out in the east of Pennsylvania, and then moved gradually but more or less progressively west, all the way to Missouri and the Mississippi River “Valley of Democracy” by the time of his death.

It probably says something about the subtle differences between the United States and Canada, even today, that Daniel Boone started out in the east of Pennsylvania, and then moved gradually but more or less progressively west, all the way to Missouri and the Mississippi River “Valley of Democracy” by the time of his death.

David Thompson’s North American career, on the other hand, started out in the most easterly part of present-day Western Canada, in what is now northern Manitoba. From here he moved more or less progressively west to the Pacific Ocean. Then he moved back east, to the St. Lawrence River and the most easterly Great Lakes. Thompson would finally spend more than half his life in present-day Ontario and Quebec. And that is where he died.

Thompson and his family only stayed in Terrebonne, northeast of Montreal, until 1815. Once he had completed his great “Map of the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada,” his obligations to the North West Company and the Montreal fur trade had ended. He managed to secure the position of astronomer and surveyor to the British commission under the Treaty of Ghent, that had ended the War of 1812-1814 between the US and the UK. And he moved his family to Williamstown, in the eastern part of Upper Canada (just northeast of the present-day city of Cornwall, Ontario).

At the time, the Williamstown, UC region was something of a North West Company retirement community. Along with other veterans of the transcontinental fur trade, Thompson’s fellow pioneer explorer of Canada’s Pacific coast region in what is now British Columbia, Simon Fraser, was living on a farm about nine miles west of Williamstown proper. (The Williamstown house in which David Thompson and his family lived is now owned by the Ontario Heritage Trust, and has been “designated a National Historic Site of Canada.”)

At the time, the Williamstown, UC region was something of a North West Company retirement community. Along with other veterans of the transcontinental fur trade, Thompson’s fellow pioneer explorer of Canada’s Pacific coast region in what is now British Columbia, Simon Fraser, was living on a farm about nine miles west of Williamstown proper. (The Williamstown house in which David Thompson and his family lived is now owned by the Ontario Heritage Trust, and has been “designated a National Historic Site of Canada.”)

Down to the early 1830s, Thompson qualified as what D’Arcy Jenish calls “a man of stature” in the Williamstown area – and he and his family seem to have been prosperous enough. But then, in an increasingly deteriorating more general economic climate, various business ventures on which he had embarked began to go sour. Whatever else, David Thompson was apparently not the kind of businessman who could prosper through thick and thin in the Upper Canada of the day – despite his quite vast achievements elsewhere.

(Here again there seems some kind of at least loose parallel with Daniel Boone. In his case too, Madison Smartt Bell tells us in the New York Review of Books, there was something of a “persistent pattern: expert as he was in exploring and hunting, Boone seldom managed to bring home his spoils.” As noted earlier, both Boone and Thompson would die penniless as well.)

In the spring of 1836 David Thompson’s Williamstown property was seized by the courts to settle business debts, and the family moved to Montreal. Thompson still had some savings to keep his brood afloat for a bit. To further restore his financial prospects somewhat he managed to obtain contract surveying work from the government of Upper Canada. This included the “1837 exploration from the east shore of Georgian Bay … through the Muskoka Lakes water system to the Ottawa river” – that was re-enacted by canoeing enthusiasts in the summer of 2007, to help kick off the “North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative.”

Thompson in this case, at 67 years of age, led one of three groups commissioned to explore alternate prospects for a canal from Georgian Bay to the Ottawa River. The only sensible prospect for any such transportation infrastructure lay along the traditional east-west fur-trade canoe route further north, following the French River, Lake Nipissing, and the Mattawa River. Thompson and his party wound up conducting an early survey of what has subsequently become the leading upscale rest and recreation paradise in the Muskoka district north of Toronto (Southern Ontario’s answer to Lake Tahoe in Northern California?).

Thompson in this case, at 67 years of age, led one of three groups commissioned to explore alternate prospects for a canal from Georgian Bay to the Ottawa River. The only sensible prospect for any such transportation infrastructure lay along the traditional east-west fur-trade canoe route further north, following the French River, Lake Nipissing, and the Mattawa River. Thompson and his party wound up conducting an early survey of what has subsequently become the leading upscale rest and recreation paradise in the Muskoka district north of Toronto (Southern Ontario’s answer to Lake Tahoe in Northern California?).

Thompson began his work at Georgian Bay in early August of 1837, in the rugged rocky Canadian Shield country that he described as “very rude and without Soil.” By this point, the wider political climate in at least some parts of the two Canadas had begun to bubble. As Jenish explains in his recent biography, during the winter of 1836-1837, as David and Charlotte and their family made their own new home in Montreal, “the community around them seethed with sectional strife and tension.”

Some of the background behind all this had to do with the still wider “financial panic” of 1837 – the “first great business panic” in North America, that almost certainly had something to do with David Thompson’s own financial difficulties (however small and inscrutable). Yet, as Jenish relates, political protest in the British North American provinces of the two Canadas – for whatever ultimate reasons – was not a cause that moved Thompson’s imagination. He “had no time for any of this. He had been stung by events in Upper Canada and had his own pressing challenges: earning a living, paying the rent and keeping his family fed and clothed.”

Some of the background behind all this had to do with the still wider “financial panic” of 1837 – the “first great business panic” in North America, that almost certainly had something to do with David Thompson’s own financial difficulties (however small and inscrutable). Yet, as Jenish relates, political protest in the British North American provinces of the two Canadas – for whatever ultimate reasons – was not a cause that moved Thompson’s imagination. He “had no time for any of this. He had been stung by events in Upper Canada and had his own pressing challenges: earning a living, paying the rent and keeping his family fed and clothed.”

By the time Thompson’s survey of the Muskoka Lakes water system to the Ottawa river was altogether winding down, at the end of 1837, he and his colleagues nonetheless learned that, while they were cutting through the still primeval lakes and forests of the more southerly Canadian Shield, “armed rebellions had occurred in both Lower and Upper Canada.” Thompson himself “saw startling evidence of the battles on the journey back to Montreal.”

On December 30, 1837 he wrote in his ever-present journal: “Came to the Grand Brul and stopped to feed the horse … Here is a sad view of the effects of ancestral Rebellion. The Church and many houses Burnt.”

6. David and Charlotte : Many Tender Métis Ties

David Thompson would live for 20 more years, after his late 60s adventures in Muskoka during the summer and fall of 1837. On some accounts these were two decades of almost (if not completely) unrelieved hard times. By the late 1840s he and Charlotte were entirely dependent on their daughter Elizabeth and her husband William Scott for their material support.

David Thompson would live for 20 more years, after his late 60s adventures in Muskoka during the summer and fall of 1837. On some accounts these were two decades of almost (if not completely) unrelieved hard times. By the late 1840s he and Charlotte were entirely dependent on their daughter Elizabeth and her husband William Scott for their material support.

When the Scotts moved from Montreal to Longueuil, Lower Canada in connection with William’s work, Charlotte and David ( and their daughter Eliza) moved with them. Then when the Scotts finally moved to Indiana, where William had accepted a engineering job, Charlotte and David moved in with Eliza and her new husband Dalhousie Landel in Longueuil. It was in the house of Dalhousie and Eliza Landel that David Thompson finally died on February 10, 1857, at the ripe old age of 87.

It was not uncommon for old people in 19th century North America to depend on their adult children for material support – as the cases of both David Thompson and Daniel Boone show. The aging David Thompson’s appeals for aid to various old colleagues were not always turned down. A Montreal doctor, Henry Howard, successfully treated Thompson for blindness caused by cataracts at the age of 78. If his map-making and exploring contributions to the development of the Canadian confederation, which would not officially even begin until a decade after his death, were not adequately recognized during his lifetime, that is hardly surprising, given the real circumstances of Canada then (and some would no doubt say, now as well).

It was not uncommon for old people in 19th century North America to depend on their adult children for material support – as the cases of both David Thompson and Daniel Boone show. The aging David Thompson’s appeals for aid to various old colleagues were not always turned down. A Montreal doctor, Henry Howard, successfully treated Thompson for blindness caused by cataracts at the age of 78. If his map-making and exploring contributions to the development of the Canadian confederation, which would not officially even begin until a decade after his death, were not adequately recognized during his lifetime, that is hardly surprising, given the real circumstances of Canada then (and some would no doubt say, now as well).

Moreover, it seems clear enough that two big things sustained and redeemed the last two decades of struggle in David Thompson’s long life.

The first was his composition of a narrative of his early western travels and adventures – especially during the time presently being celebrated as the North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative, 1807-1811. This he undertook in the 1840s, as a potential way of earning enough income to independently support his and Charlotte’s old age. As with everything else he tried to this end, the scheme never did succeed in this respect. But a version of the manuscript he wrote would finally be published in the early 20th century. And there are increasing numbers of Canadians in the early 21st century who believe it constitutes his best legacy to the modern Canadian confederation he helped define in the 19th century.

The first was his composition of a narrative of his early western travels and adventures – especially during the time presently being celebrated as the North American David Thompson Bicentennials Initiative, 1807-1811. This he undertook in the 1840s, as a potential way of earning enough income to independently support his and Charlotte’s old age. As with everything else he tried to this end, the scheme never did succeed in this respect. But a version of the manuscript he wrote would finally be published in the early 20th century. And there are increasing numbers of Canadians in the early 21st century who believe it constitutes his best legacy to the modern Canadian confederation he helped define in the 19th century.

The second big thing that sustained and redeemed the last 58 years of David Thompson’s long life – and that may finally constitute a still more impressive and interesting legacy for the Canadian future – was his long and (it would clearly if not altogether explicitly seem, from a multitude of sources) very successful marriage to Charlotte Small.

Charlotte herself came from what the Canadian Constitution Act 1982 now calls “the Métis peoples of Canada.” Her mother was Cree and her father Scottish. When her father left the fur-trading country in the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada, after a successful career there, he did not bring his “country wife” nor his children with him. All this was common enough in the northern North American universe of the 18th and 19th centuries – and raised no eyebrows, in the east or the west.

Charlotte herself came from what the Canadian Constitution Act 1982 now calls “the Métis peoples of Canada.” Her mother was Cree and her father Scottish. When her father left the fur-trading country in the North-West Territory of the Province of Canada, after a successful career there, he did not bring his “country wife” nor his children with him. All this was common enough in the northern North American universe of the 18th and 19th centuries – and raised no eyebrows, in the east or the west.

When David Thompson left the North-West territory in 1812, to retire back east, he might have done the same as Charlotte’s own father – and she could at least have not been altogether surprised. Instead he took his Indian country family back east with him. He had already married Charlotte according to the customs of the Cree. But one of the first things he did when his family settled in Terrebonne was confirm the point, “according to the requirements of the colonial administration” in Lower Canada.

As D’Arcy Jenish explains in his recent biography, David Thompson “became fluent in French, Cree and likely Blackfoot and acquired a working knowledge of several other native languages.” And he “took a country wife of aboriginal descent, a common practice among fur traders, but defied convention and settled with her and their children in a pioneer society where bigotry and prejudice were prevalent.”

As D’Arcy Jenish explains in his recent biography, David Thompson “became fluent in French, Cree and likely Blackfoot and acquired a working knowledge of several other native languages.” And he “took a country wife of aboriginal descent, a common practice among fur traders, but defied convention and settled with her and their children in a pioneer society where bigotry and prejudice were prevalent.”

As the film maker Tom Radford has somewhat more exotically put the matter: “In the course of his journeys, Thompson married a Mtis woman, Charlotte Small, “The Woman of the Paddle Song.” Travelling by birch bark canoe, teaching each other the peculiarities of a different culture, they were among the first explorers of what it means to be Canadian.”

In the Canada of the early 21st century, where some new mixed-race Middle Ground so clearly seems to be arising, especially on the streets of such diverse larger urban areas as Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg,Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax (and so forth), this may finally prove to be the side of both David and Charlotte Thompson, as what Jenish calls “foundational figures,” that actually does seem most impressive for the Canadian future. Canada, like other parts of North America too no doubt, is a place where almost all the peoples of the global village have finally come to mix and mingle. And somehow David Thompson seems to have at least vaguely grasped that something of this sort would eventually happen, as long ago as the early 19th century. That is what is most interesting about the ongoing transcontinental (and multidimensional) experiment, that the diverse associates of the old North West Company helped begin to clarify long ago. And once again in Canada today, you can get the feeling that something about the the rugged romance of the old northern resource economy does have fresh relevance of some sort for the current local scene, from the Atlantic to the Arctic to the Pacific seas …

In the Canada of the early 21st century, where some new mixed-race Middle Ground so clearly seems to be arising, especially on the streets of such diverse larger urban areas as Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg,Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax (and so forth), this may finally prove to be the side of both David and Charlotte Thompson, as what Jenish calls “foundational figures,” that actually does seem most impressive for the Canadian future. Canada, like other parts of North America too no doubt, is a place where almost all the peoples of the global village have finally come to mix and mingle. And somehow David Thompson seems to have at least vaguely grasped that something of this sort would eventually happen, as long ago as the early 19th century. That is what is most interesting about the ongoing transcontinental (and multidimensional) experiment, that the diverse associates of the old North West Company helped begin to clarify long ago. And once again in Canada today, you can get the feeling that something about the the rugged romance of the old northern resource economy does have fresh relevance of some sort for the current local scene, from the Atlantic to the Arctic to the Pacific seas …

Meanwhile, one thing we do know quite exactly about David Thompson in his oldest age is that, according to his grandson, William David Scott, the old man “cared nothing for society and showed a preference for the companionship of his wife rather than anybody else.” Charlotte would seem to have returned the favour. She died at the age of 71 on May 4, 1857, only three months after her husband’s death.

C.M.W. Marcel would like to thank his colleagues at the Linsmore Institute on Danforth Avenue in Toronto.

i am the great great grandson of a shanty irishman who settled in north hastings [madoc] in the 1840s . my mothers side desend from an english bond slave and an indian male who settled in madoc at about the same time. on my fathers side we number roughly 1400 desendents from this one irishman. im damn proud to be canadian… what shames me is why some people need to compare our history and acomplishments with the americans, like we need them to pat us on the head. our history can stand on its own.its richer and longer and not near the “god damn ” lies. p.s. throw that phoney daniel boone off the page, ive read his real accounts; he doesnt deserve to be there…/

Spent 5 days in Van. during 1971 and beautiful B.C. is something to be proud of . Sincerely yours , David nz..