The Sparrow’s guide to baseball Blue Jays 2009

Apr 8th, 2009 | By Rob Sparrow | Category: Sporting Life As we slowly edge into spring after a long winter of much economic turmoil it is once again time to focus in on more simple pursuits. The economic tsunami has engulfed the world, and its reach and effects extend to all corners of the global village. With that in mind, we begin our annual baseball journey with the recently completed World Baseball Classic (WBC), and look for wider answers in some perhaps unlikely places. Then we consider “baseball as microcosm,” to probe underlying fault lines that may have rumbled the US economy too. We go on to look at the increasing number of Latin American ballplayers – as a case of what’s called the outsourcing trend in other branches of American business. Then we explore the theory that baseball will be the first of the major sports to be hurt by the general economic downturn in North America. Finally we turn directly to our beloved Blue Jays. We start with a review of the mediocre life and times of general manager JP Ricciardi. Then we offer our Blue Jays outlook 2009. We have to happily note that they have already won their season opener against the Tigers at the Rogers Centre, on a snowy night in early April (and their second game as well). But our sense is still that the 2009 Jays are mostly trying to get their youngsters ready for 2010 and beyond. They are willing to sacrifice this season for a hopeful later harvest.

As we slowly edge into spring after a long winter of much economic turmoil it is once again time to focus in on more simple pursuits. The economic tsunami has engulfed the world, and its reach and effects extend to all corners of the global village. With that in mind, we begin our annual baseball journey with the recently completed World Baseball Classic (WBC), and look for wider answers in some perhaps unlikely places. Then we consider “baseball as microcosm,” to probe underlying fault lines that may have rumbled the US economy too. We go on to look at the increasing number of Latin American ballplayers – as a case of what’s called the outsourcing trend in other branches of American business. Then we explore the theory that baseball will be the first of the major sports to be hurt by the general economic downturn in North America. Finally we turn directly to our beloved Blue Jays. We start with a review of the mediocre life and times of general manager JP Ricciardi. Then we offer our Blue Jays outlook 2009. We have to happily note that they have already won their season opener against the Tigers at the Rogers Centre, on a snowy night in early April (and their second game as well). But our sense is still that the 2009 Jays are mostly trying to get their youngsters ready for 2010 and beyond. They are willing to sacrifice this season for a hopeful later harvest.

World Baseball Classic – a new world order here too

For the second consecutive time, in 2009 Japan was victorious in the WBC with its thrilling 5-3 extra inning victory over its perennial rival Korea. What made the outcome more surprising was not the result in itself. It was the general consensus of all who watched (or cared to watch) that the two Asian baseball powers were the class of the tournament. Imperceptibly, the pendulum has shifted. The best and most complete baseball is now being played in the Far East.

For the second consecutive time, in 2009 Japan was victorious in the WBC with its thrilling 5-3 extra inning victory over its perennial rival Korea. What made the outcome more surprising was not the result in itself. It was the general consensus of all who watched (or cared to watch) that the two Asian baseball powers were the class of the tournament. Imperceptibly, the pendulum has shifted. The best and most complete baseball is now being played in the Far East.

Americans have always prided themselves as being the home of baseball – the enduring democratic pastime that is as much a part of the culture as apple pie, the hamburger or the automobile. But for those who were watching the 2009 WBC, Japan taught the United States a lesson with its 9-4 semifinal victory that eliminated the US from the competition. And its recipe was distilled in a unique Asian baseball way: attention to detail, precise work habits, left-handed contact hitting and near-flawless defence. As American center fielder Shane Victorino noted, “They want to play the game of baseball as perfect as they can.” He also remarks how even during pitching changes in the middle of an inning, the Asian teams will take infield practice. “We stand around and talk to each other,” Victorino said.

Look further at the pre-game practices. The Japanese run the baseball equivalent of a precise three-ring circus, with players taking groundballs and flyballs all over the field at game speed. The Americans take a half-speed approach, and you’ll almost never catch them taking pre-game infield and outfield practice as a team.

Look further at the pre-game practices. The Japanese run the baseball equivalent of a precise three-ring circus, with players taking groundballs and flyballs all over the field at game speed. The Americans take a half-speed approach, and you’ll almost never catch them taking pre-game infield and outfield practice as a team.

Yes, baseball is the American pastime, but the United States once invented and popularized the automobile. Look at Detroit today and tell me it’s still doing the car business better than Asia. Reputation alone is not a winning business model.

The American game, for better or for worse, has moved to lavish new stadiums and supports lucrative player contracts. It is built on power and entertainment – a deadly combination, we’ve discovered, in an era of performance-enhancing drugs. Meanwhile, nations like Japan and Korea have learned the game, digested it and improved upon it by going back to the basics.

“‘The world has caught up with us,” Bob Watson, a Major League Baseball vice president said dejectedly after the US loss. Indeed it has.

Dropping the ball … and the African American ballplayer

It doesn’t take too much imagination to see this as indicative of wider issues in American sports and even US culture at large – the propensity for the immediate, the glorification of the individual, and the hubris about superior methods. Perhaps by looking within “baseball as microcosm” we can unearth some of the underlying fault lines that have also pushed the US economy to the brink.

It doesn’t take too much imagination to see this as indicative of wider issues in American sports and even US culture at large – the propensity for the immediate, the glorification of the individual, and the hubris about superior methods. Perhaps by looking within “baseball as microcosm” we can unearth some of the underlying fault lines that have also pushed the US economy to the brink.

Baseball is a game of repetition, of subtle and specific skill. It takes time and effort, practice and good coaching, to understand its many intricacies, complexities and subtleties, and to hone those instincts so that you can understand what you have to do, before you have to do it. It is no wonder that baseball more than any other sport follows a kind of apprenticeship methodology to teach its craft and tools of the trade.

This is reflected in its established minor league system with its many levels that work to refine a player’s skills and teach the nuances of the game. Traditionally a player will play anywhere from four to eight years in the minor leagues before ever earning a major league cheque. Baseball as a sport is the epitome of delayed gratification.

It is this because of this underlying time commitment that many American amateur athletes are now choosing to eschew baseball in search for more immediate fame and payoff. Consider that in other sports, college and even high school players often make the leap to the NHL, NBA or the NFL and become starters, and even standouts in their first year in the pros – enjoying the glamour and accompanying money. But that is not the case with baseball. Even outstanding players who have excelled at every level of the game from the time they were in T-ball spend several years in the minor leagues honing their skills before they are ready for prime time.

It is this because of this underlying time commitment that many American amateur athletes are now choosing to eschew baseball in search for more immediate fame and payoff. Consider that in other sports, college and even high school players often make the leap to the NHL, NBA or the NFL and become starters, and even standouts in their first year in the pros – enjoying the glamour and accompanying money. But that is not the case with baseball. Even outstanding players who have excelled at every level of the game from the time they were in T-ball spend several years in the minor leagues honing their skills before they are ready for prime time.

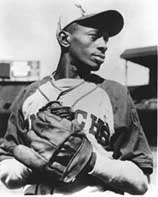

This is one factor that has also led to an interesting new phenomena afflicting baseball over the last 30 years – the disappearance of the African American ballplayer. From 1946 to the 1970s, the number of African Americans in the game was consistently on the rise. One by one, teams de-segregated and baseball as a whole grew in terms of quality of play and excitement for the fans. Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Satchel Paige and a myriad of other African American players left an indelible mark on the game, setting new standards, breaking records, and welcoming a new generation of African Americans into major league baseball. A combination of reasons, however, have systematically reduced the number of African American players in baseball from a peak of 28% in 1975 down to just 8% in 2008.

First, other college and major league sports, most notably football and basketball, have siphoned away the interest of young African American athletes. Most kids and parents in their communities have subscribed to the mind-set that money, fame, opportunity, and acceptance are more accessible in football and basketball than in the much more difficult path of baseball.

First, other college and major league sports, most notably football and basketball, have siphoned away the interest of young African American athletes. Most kids and parents in their communities have subscribed to the mind-set that money, fame, opportunity, and acceptance are more accessible in football and basketball than in the much more difficult path of baseball.

The fact is that in today’s African American community, basketball is the game to play and football is the game to watch. Hip, tough NBA and NFL players have become heroes and icons for the younger generation, a fact that sports marketing has capitalized on.

This shift has been going on for some time and baseball now has the lowest support of black fans relative to white fans of the three major sports. Approximately 17% of the NBA fan base is African American, NFL at 11.5%, and baseball lower still at 6.8%. United States baseball is losing a generation of fans and more importantly some of its best athletes.

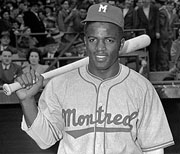

An indication of the limited future of the African American in baseball comes from a recent NCAA College World Series (the championship of US universities). Less than 4% of the players were African American and there were no African American head coaches on any of those teams. Where have you gone, Jackie Robinson?

Outsourcing of the game

It is with economics in mind that we shift to another reason fewer African Americans are making it to the major-league level. Their precipitous fall in numbers has somewhat been offset by the increasing number of Latin American ballplayers who have come to dominate the game. Few people in or out of baseball are aware of the reasons behind this shift in demographics. Yet the transformation in not unlike other major American businesses where outsourcing has become a more viable and cost-effective business approach.

It is with economics in mind that we shift to another reason fewer African Americans are making it to the major-league level. Their precipitous fall in numbers has somewhat been offset by the increasing number of Latin American ballplayers who have come to dominate the game. Few people in or out of baseball are aware of the reasons behind this shift in demographics. Yet the transformation in not unlike other major American businesses where outsourcing has become a more viable and cost-effective business approach.

Case in point: a top-quality baseball prospect from the United States is going to cost a team three or four million dollars to draft and sign. Even a quality player not picked in the first round with a decent chance of making it to the majors is still a million-dollar gamble. This is where the issue of money comes in big. The rules regarding signing bonuses for players born in the United States simply do not apply to those born outside its borders.

Much as American corporations look to offshore operations to reduce overhead, Major League owners are looking to “outsource.” They have hedged their bets on foreign-born Latin players by building academies in these countries to scout, sign, and teach talent. The fact is, the rules there are different for signing; the age is younger, and it is much, much less expensive.

Major League Baseball has developed what insiders have called a “boatload mentality” toward Latin American players. The teams can buy a boatload of players for the same amount of money it costs to sign one player born in the United Sates. Hence, many think it is a safer bet to sign twenty Latin American ballplayers who have done nothing but eat, sleep, dream and play baseball as a way of elevating them from their existing plight.

Major League Baseball has developed what insiders have called a “boatload mentality” toward Latin American players. The teams can buy a boatload of players for the same amount of money it costs to sign one player born in the United Sates. Hence, many think it is a safer bet to sign twenty Latin American ballplayers who have done nothing but eat, sleep, dream and play baseball as a way of elevating them from their existing plight.

This phenomena in baseball somewhat resembles the shift toward Wal-Mart economics that has come to dominate the American mind-set over the past 30 years. By demanding that goods sold to the American consumer be priced so low and corresponding supplier profit margins so thin, the big box retailers, epitomized by Wal-Mart, have been driving a massive restructuring of production worldwide – moving jobs from the US and Europe to Asia where only lowest-cost labor can meet the targets. In the process America has outsourced its capacity to produce and has become in turn a land of consumers.

In baseball too, it is finally just a matter of economics. But it is also a systemic problem that helps explain why American baseball has regressed and other nations have caught up. In any case economics dictates that you look not to American inner cites for you future stars but (in true Monroe Doctrine form) to the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Panama, Venezuela, and other points south.

Perhaps with a touch of hubris America still feels that it owns the game of baseball, and that both baseball and the US economy will be alright in the end. Yet is was not too long ago that many within the Wall Street financial system were drinking their own Kool-aid, inside economic models that lionized a system which finally proved a house of cards. It was the McLuhanist equivalent of “going forward through the rear view mirror.” As we continue to go forward, American baseball and more importantly the present American system at large (and we Canadians who are so closely connected, of course) have to ask how a place that increasingly makes nothing, that builds nothing, that only services and outsources, can still expect to stay on top of the economic totem pole, in the global village we all now live in at last?

Economic downturn to affect baseball first?

Many believe that baseball will be the first of the major sports to be affected by the general economic downturn. It is after all the first to effectively begin a season in the new business climate. This was demonstrated in the offseason, where many club managements slashed their staffs in an effort to cut costs. The trend was also felt very close to home as the Rogers Blue Jays laid off 40 front office staff and cancelled its annual Christmas function. (Ba humbug!)

Many believe that baseball will be the first of the major sports to be affected by the general economic downturn. It is after all the first to effectively begin a season in the new business climate. This was demonstrated in the offseason, where many club managements slashed their staffs in an effort to cut costs. The trend was also felt very close to home as the Rogers Blue Jays laid off 40 front office staff and cancelled its annual Christmas function. (Ba humbug!)

The downturn is also likely going to be felt in the stands this year, as people with less and less disposable income look to trim their budget. Places hard hit in the economic crisis such as Detroit (whose season-ticket base has been cut almost in half), along with other cities in the American rust belt, will be hard pressed to fill their ballparks – as their regions contend with tremendous rises in unemployment, foreclosures, and personal bankruptcies.

Timing might also not be good for both New York teams, as they each move into new multi-billion dollar facilities. The downfall of Wall Street and the huge hit on business in the city has already impacted the sale of luxury suites and sales at the gate. The teams bear only so much blame. The plans for both parks were formulated when the economy was in much better shape. Yet the timing of the respective openings, needless to say, has proved quite unfortunate.

Overall, it will be interesting to see the effect throughout the summer. In tough times people look for distractions, and interestingly the movie industry is experiencing a boom year that was not anticipated. That said, the price point for sports is a little above that of the local movie, and it may well be increasingly difficult for a family of four to shell out $250 for a day at the old ballpark.

JP Ricciardi and the Jays eight is enough

When JP Ricciardi was named General Manager of the Blue Jays in 2001 there was a lot of hype surrounding his appointment. He belonged to a new generation of baseball executives, who eschewed traditional ways for statistical analysis and the great new game of “Moneyball.”

When JP Ricciardi was named General Manager of the Blue Jays in 2001 there was a lot of hype surrounding his appointment. He belonged to a new generation of baseball executives, who eschewed traditional ways for statistical analysis and the great new game of “Moneyball.”

This new breed was somewhat contemptuous of their older brethren, and a little cocky to boot. So JP in his original press conference treated the “neophyte” Toronto media with disdain when he coyly remarked: “I have forgotten more than you will ever know about baseball.” With this in mind, let us not forget the truth of what has happened since then, as we take a flashback to his original game plan, and then review his reign of mediocrity:

JP’s four-point Moneyball plan of 2001:

i) Improve the Farm system

In true JP form, Ricciardi threw the outgoing management under the bus when he started in 2001. He claimed that the minor league system he was left with had no bonafide prospects, and that he was going to be operating with limited resources.

Time has told a different story, as the previous administration headed by former Blue Jay GM Gord Ash had left the Blue Jays with one of the top pitchers of the decade Roy Halladay, and also a perennial all star and gold glover in Vernon Wells and a budding five tool player in Alex Rios. Ricciardi during his regime can boast of developing noone of that pedigree and subsequently his tenure will leave no such lasting legacy from which to build upon.

ii) Drafting College Players

As examples of the previous administration’s lack of winning ways, Ricciardi cited their concentration on drafting high school players (Halladay and Wells, e.g.), and their failure to use the US college system properly. His Moneyball view was that college players were closer to major-league-ready, and that he could use statistical analysis to track and find better players.

As examples of the previous administration’s lack of winning ways, Ricciardi cited their concentration on drafting high school players (Halladay and Wells, e.g.), and their failure to use the US college system properly. His Moneyball view was that college players were closer to major-league-ready, and that he could use statistical analysis to track and find better players.

That myopic attitude has turned out to be a disaster, compounded by decisions that in turn were both shortsighted and incorrect. And all this has only served to put the Jays years behind more forward-thinking teams like the Tampa Bay Rays. Ricciardi’s drafting of college players has netted only two marginal players in his eight years on the job: Aaron Hill and Adam Lind. And it was only within the last two years that, through outside pressure, he changed tack and started to draft high-school players himself. This led to the Jays selecting Travis Snider in the 2007 draft, who many now believe to be the future of the franchise.

iii) Too many veteran players with big contracts.

Part of what sold the Toronto executive (mainly Paul Godfrey) on Ricciardi was his mantra that there were too many older players making millions of dollars and that younger cheaper players could fill the gaps at a much lesser cost. As mentioned, his drafting of young players has been atrocious, and that has led to players not developing at the major league level. This has subsequently led to Riccardi’s having to sign much more expensive veterans to make up for the deficiencies – in direct contradiction to his original plan!

iv) Carlos Delgado’s contract was an albatross that tied his hands

Ricciardispecifically singled out Carlos Delgado’s four-year $69M contract when he was touting his “Moneyball” mantra of younger cheaper players and fiscal responsibility. He claimed that Delgado’s large contract was an albatross, which left him with no payroll flexibility to make smart moves in his first couple of years. And he believed that when Delgado’s contract came off the books, he could use the money more shrewdly.

Yet what Ricciardihas in fact demonstrated is an endless display of continued fiscal mismanagement. It started with the ill-advised long-term deal with Eric Hinske. And it has continued right up to today, with existing big-money commitments and long-term contracts with players who are injured and past their prime (BJ Ryan and Scott Rolen). And even this pales in comparison with the $130M dollar commitment to Vernon Wells, a one time all-star whose best seasons may be a thing of the past. Wells is signed for $22M a year till 2014 – the current big albatross of a contract unfortunately awaiting the next incoming administration.

Yet what Ricciardihas in fact demonstrated is an endless display of continued fiscal mismanagement. It started with the ill-advised long-term deal with Eric Hinske. And it has continued right up to today, with existing big-money commitments and long-term contracts with players who are injured and past their prime (BJ Ryan and Scott Rolen). And even this pales in comparison with the $130M dollar commitment to Vernon Wells, a one time all-star whose best seasons may be a thing of the past. Wells is signed for $22M a year till 2014 – the current big albatross of a contract unfortunately awaiting the next incoming administration.

In summary, for years Ricciardi has played the we-can’t -compete-with-the-Red -Sox-and- Yankees card. But he never said anything about the we-can’t-compete-with-the-Tampa-Rays card. Yet it actually hasn’t mattered how the power has been altered in the American League during Ricciardi’s time in Toronto. The math has been quite similar.

In the 14-team American League, the Blue Jays are better than seven teams, not as good as six. They are, just about every year, good enough to believe they’re close – just never close enough to find a way to the post-season, or even a legitimate race for a playoff spot. The plain fact is that last year the Jays had their eighth straight season missing the playoffs, in Ricciardi’s tenure. In all of baseball they are among only seven franchises that have not reached the post-season this decade (Cincinnati, Texas, Pittsburgh, Kansas City, Baltimore and Washington/Montreal). And all of those teams have changed management: no other current GM can match Riccardi’s streak of having his Octobers off!

Frankly, anybody can be in the middle of the pack, but the Toronto fans deserve better. As an organization you have to have something to believe in, and that was the main reason that Cito Gaston was taken off the shelf last year – to invigorate a dying franchise. Toronto fans now have a proven manager that can get them there, they have parts of a pitching staff that beyond current injuries will see better days, and an every-day lineup that needs some tweaking and teaching. But if the ultimate assessment of any general manager is his win-loss record (and as legendary football coach Bill Parcells has been quoted :”you are your record”), then what the Jays don’t have is the right leader.

Frankly, anybody can be in the middle of the pack, but the Toronto fans deserve better. As an organization you have to have something to believe in, and that was the main reason that Cito Gaston was taken off the shelf last year – to invigorate a dying franchise. Toronto fans now have a proven manager that can get them there, they have parts of a pitching staff that beyond current injuries will see better days, and an every-day lineup that needs some tweaking and teaching. But if the ultimate assessment of any general manager is his win-loss record (and as legendary football coach Bill Parcells has been quoted :”you are your record”), then what the Jays don’t have is the right leader.

Vision is a big part of being a GM, in any sport, any professional team. You have to understand winning, you have to have a feel for success, and you have to know that players are more than just their numbers. Some GMs – like Toronto Blue Jay builder and current World Series winner Pat Gillick – always find a way to get it done. Some like Ricciardi never seem to. There was hype surrounding him in November of 2001. There is no hype now.

Blue Jays Outlook 2009

The American League East where the Blue Jays compete is the toughest division in baseball, and the primary battleground for the entire sport. The Yankees, Red Sox, and Rays are the three best teams in baseball today, and yet at least one of them is guaranteed to miss the playoffs. “It’s going to be a frickin’ war in that division,” said A’s general manager Billy Beane. Seven of the past 12 teams to play for the AL championship (and 12 of the past 22) have come from the AL East. So odds are at least one of the AL East big three will be in the AL championship series.

The American League East where the Blue Jays compete is the toughest division in baseball, and the primary battleground for the entire sport. The Yankees, Red Sox, and Rays are the three best teams in baseball today, and yet at least one of them is guaranteed to miss the playoffs. “It’s going to be a frickin’ war in that division,” said A’s general manager Billy Beane. Seven of the past 12 teams to play for the AL championship (and 12 of the past 22) have come from the AL East. So odds are at least one of the AL East big three will be in the AL championship series.

That leaves us with the Jays, once again on the outside looking in. Last season the Jays went on to post the best team ERA in baseball – an amazing accomplishment for an American League team that operates both with the DH, and in the most offensively frightening division in baseball. But with starters Dustin McGowan and Shaun Marcum both having season-ending surgery and with AJ Burnet skipping his way out of town, the starting pitching will suffer. The Jays’ bullpen is going to have an awful lot of work to do this year. Every outing for rookies David Purcey, Ricky Romero, and Scott Richmond will be an adventure, walking the high wire of mediocrity.

Pitching, however, is not the club’s only concern. So is the Jay’s offense, which last season sputtered with a .264 batting average (10th in the American League) while scoring on average only 4.4 runs a game (11th in the AL). The Jays are hoping for rebound years from Vernon Wells, whose production has fallen following two injury-marred season, and Alex Rios, who regressed last year to hit only 15 homers and knock in 79 runs. Others who need hitting rebounds are first baseman Lyle Overbay and third baseman Scott Rolen, both of whom dramatically underperformed last year.

If the Jays get off to a slow start, the vultures will start circling, and there will be trade rumours about the team’s current best player, Roy Halladay. He has been a perennial all-star over his years, while also emerging as the face of the franchise. That said, I really don’t see him in a Jays’ uniform on opening day 2010. That will be the final year of his current contract, and by that time the new management Paul Beeston will have put in place will want to maximize the return that they can get in a deal for him for the future betterment of the whole ball club.

If the Jays get off to a slow start, the vultures will start circling, and there will be trade rumours about the team’s current best player, Roy Halladay. He has been a perennial all-star over his years, while also emerging as the face of the franchise. That said, I really don’t see him in a Jays’ uniform on opening day 2010. That will be the final year of his current contract, and by that time the new management Paul Beeston will have put in place will want to maximize the return that they can get in a deal for him for the future betterment of the whole ball club.

What the Jays are trying to do as an organization is to get the youngsters ready for 2010 and beyond without investing money in any outside help. They are willing to sacrifice this season for the development of players and hopefully a later harvest.

The Jays won 86 games last year. But the last time they won 86 in 2003, they followed it up with a 67-win effort in 2004. That could happen again unless two of the three young starting pitchers (Purcey, Richmond, and Romero) step up and blossom. And, the way things look right now, this figures as something of a longshot. All in all the Toronto faithful will once again have to be patient this summer, along the shores of Lake Ontario. But with an ongoing change in vision and management, and a commitment back to old time Blue Jay stewardship, the fan base will soon have something they can believe in again.

Two key sources

George Will, Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball, Harper Paperbacks, 1991.

George Will, Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball, Harper Paperbacks, 1991.

Dave Winfield, Making the Play: How to get the best of Baseball Back, Scribner, 2008.

Robert Sparrow is a Toronto marketing analyst and noted local authority on the sporting life.