Remembrance of coalitions passed … and the Canadian rebellion tradition

Dec 6th, 2009 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In Brief

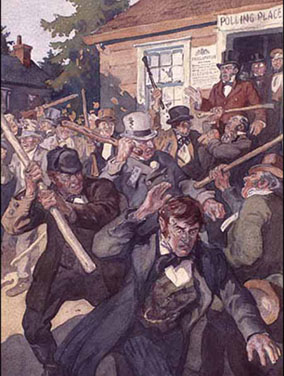

C.W. Jefferys’ famous enough sketch of the December 5 march down Yonge Street in the Upper Canadian Rebellion of 1837. Not for the last time angry people would try to attack the provincial capital in Toronto.

TORONTO. SUNDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2009. Yesterday marked the 172nd anniversary of William Lyon Mackenzie’s ill-fated (and no doubt somewhat comic-operetta) march down Yonge Street in a much earlier incarnation of this city – the height, as it were, of the Upper Canadian Rebellion of 1837.

On a perhaps vaguely related but much more recent wave of Canadian political history, this past Friday the (sometimes) high-minded Montreal Conservative L. Ian Macdonald, “Editor-in-Chief of Policy Options, Canada’s premier public policy magazine,” wrote in the National Post: “It is a year to the day since Michaelle Jean prorogued the House of Commons to end the threat of the newly re-elected Harper government being overthrown by the Three Stooges Coalition.”

This past Friday as well the final installment of NDP operative Brian Topp’s six-part series, “Coalition redux,” appeared on the Globe and Mail website. For Mr. Topp, who was intimately involved in the experiment, last year’s failed attempt to forge a Liberal-New Democrat alliance that, with the support of the Bloc Quebecois, could take over from a Harper minority government which had just done something very stupid, was not at all a “Three Stooges Coalition.” It was “the opportunity Canada missed because we did not succeed … an idea slightly before its time.”

In our view Brian Topp’s series on the failed progressive Coalition attempt in Canadian federal politics a year ago now is marred by a vain commercial for his leader Jack Layton at the very end. But we’d agree with his characterization of what the attempt was all about, over the aggressively partisan characterization of L. Ian Macdonald. (For one thing, only two of the stooges were actually involved in “the coalition.” M. Duceppe’s party had only agreed to support the experiment at arm’s length, for “a term going to June 2011 to permit two budgets.”)

In our view too, Mr. Topp’s series is worth struggling through in its entirety, in all of parts one, two, three, four, five, and six. We would not even try to summarize his story in any shorter space. We are happy to note, however, that we do agree as well with his essential characterization of the prorogation of the Canadian House of Commons, through which minority Prime Minister Stephen Harper ultimately evaded his constitutional accountability to the elected branch of our parliamentary democracy.

In Mr. Topp’s own words: “I believe the Prime Minister committed a gross act of disrespect toward the House of Commons on December 4, 2008 … The House of Commons is the only elected institution in Canada’s federal government. Unlike the Senate, the Governor-General or the prime minister and his retinue, the House is a democratic institution, our only federal democratic institution. …Â It was therefore entirely inappropriate, democratically illegitimate and improper in 2008 for Mr. Harper to direct an appointed official, the Governor-General, to instruct the majority in the House of Commons on when it can sit or what business it can conduct, so that the Prime Minister could avoid a confidence vote.”

* * * *

A mid 19th century election in Upper Canada. C.W.Jefferys. There was no secret ballot until 1874. So voting could sometimes be a little dangerous, or as some would say, manly. And of course only men could vote.

At the risk of altogether violating the spirit of a posting “In Brief,”we have a few further and somewhat extended comments on, as it were, “lessons learned” from last year’s failed Liberal-NDP coalition experiment in Ottawa, inspired by both Brian Topp’s “Coalition redux” and  L. Ian Macdonald’s “Recalling the coalition crisis.” (And perhaps the importance of the subject will excuse the violation of the in-brief editorial principle? Or so we hope, at least.)

To start with, in Mr. Topp’s view the Coalition’s “fundamental strategic mistake” was its too close identification with Gilles Duceppe and his party. Right at the start a Conservative colleague had said to him “You’re gonna run the government with separatists?” And Topp now speculates: “In hindsight, I should have thought more carefully about the implications of that question. From the first moments when Mr. Harper‘s team turned their minds to the prospect of a combined opposition coalition, they knew that its key vulnerability was the role of the Bloc Québécois.”

This seems to us, at best, an excessively Western Canadian point of view. (And in an earlier incarnation Brian Topp was in fact deputy chief of staff to Saskatchewan premier Roy Romanow.) With our own heads perhaps a bit too much stuck in the sands of Georgian Bay – in at least one of the most beautiful parts of Ontario – we think Chantal Hébert was closer to the mark in her December 4 story in the Toronto Star, “Bloc wasn’t coalition’s worst flaw.”

Mr. Topp himself addresses this point in part six of his series, where he writes: “In her column in the Toronto Star on Friday, Ms. Hébert argues that the biggest mistake we made in these events was not the prominent role of the Bloc Québécois, but the decision to retain Stéphane Dion as putative prime minister … That is a fair argument.”

In slightly more depth, Ms. Hébert points out that: “Even as they put the finishing touches to their deal, there still was no clarity as to the status of the person who would actually lead the coalition government … Topp writes that he inferred, from the beginning, that Dion might use the coalition to undo his resignation and become more than an interim prime minister. To keep all Liberal factions on side, that issue was never resolved.” And this was, she suggests, the ultimate “Liberal poison pill left in place by those who crafted the coalition.”

All this has helped us come to our own somewhat related conclusion. Our ad hoc focus group research in our Southern Ontario environs, in the immediate wake of the Coalition’s failure a year ago now, suggested that it was the prospect of Stephane Dion as prime minister that put off even many New Democrat (and even a few Liberal?) voters – or at least made them quite sceptical about this particular Coalition project. But the crux of the issue here seemed to be: how does someone whose party had won not much more than half as many seats as Stephen Harper’s party credibly wind up as prime minister? Isn’t there something a bit fishy about that, at best?

* * * *

You could say that this just reflects the extent to which the traditional inner logic of parliamentary democracy has increasingly faded from view in our Canadian political culture (so influenced in this as in so many other respects by the so often overwhelming presence – and pressure, inadvertent as it may be – of the elephant next door).

As Mr. Topp himself notes (in his own words), the traditional fundamental proposition of Westminster or British-style parliamentary government is that whoever can command a majority of seats in the popularly elected parliament becomes prime minister. Yet so many among us nowadays do seem to think that the operative proposition is more like: whatever leader of whatever party wins the largest number of seats in an election becomes prime minister. And on this basis how could M. Dion, who had clearly not won anything remotely like the largest number of seats in the October 14 election, become prime minister?

It is presumably this last kind of calculation that finally prompts L. Ian Macdonald to pronounce: “While the 2008 opposition coalition was constitutionally legal, it was politically illegitimate.” We are not at all sure that this is in fact the right philosophical formulation. The 2008 opposition coalition certainly proved to be politically unwise, or inept. But, just for starters, the phrase “politically illegitimate” almost seems to be an oxymoron – or contradiction in terms.

For the time being, however, we’ll leave aside the deep philosophical issue. Whether we like it, or even remember it, or not, the fundamental principle of our system of government is still that whoever can command a majority of seats in the democratically elected parliament becomes prime minister. In the end, there is no other practical way for a parliamentary democracy to work – no matter how many laws about fixed election dates and so forth parliament itself may pass. (As Mr. Harper himself proved by calling the 2008 federal election itself, in contradiction to his own fixed election date legislation – and legally enough according to the Supreme Court!)

Yet as best we can make out, the sum of all of Brian Topp’s, L. Ian Macdonald’s and Chantal Hébert’s wisdom about the 2008 opposition coalition is that, as a practical matter, for the concept to work – both constitutionally and politically – the parties forming the actual coalition government must together have a majority of seats in parliament themselves. And as a practical matter in current Canadian politics that almost certainly or at the very least probably means the Liberals and New Democrats together must command a majority of seats. (Which they certainly did not in the house elected on October 14, 2008.)

This is finally quite important, it seems to us, because we also agree with another of Brian Topp’s pronouncements: “We can have both a democratically representative multi-party democracy, and a stable, effective national government. By looking to our political parties to find ways to work more closely and effectively together.” And, again, we agree with Mr. Topp that the failed 2008 opposition coalition was “the opportunity Canada missed … an idea slightly before its time.”

* * * *

To revert back to our Ontario parochialism for a moment, the 1837 Rebellion in the old colonial Province of Upper Canada might also be described, more or less, as an “opportunity Canada missed … an idea slightly before its time.” And then, in a suitably revised form, its time finally came with the achievement of what generations of dull-as-ditchwater Canadian political history have called “responsible government” (i.e. colonial parliamentary democracy, if you like) in the United Province of Canada in 1848.

To expand our regional perspective here, as should be done of course, the 1837 Rebellion in Upper Canada was a twin of sorts to the more robust 1837-38 Rebellion in Lower Canada (and a cousin to the more measured protests of Joseph Howe on the Atlantic coast). Its immediate precursor was the so-called Pontiac’s Rebellion (or the Conspiracy of Pontiac) in 1763, led by the War Chief of the Ottawa who has also given his name to a now defunct brand of North American automobile. And its almost mystical Western successors were the Red River Rebellion of 1869 and the North West Rebellion of 1885, both led by the ill-fated Louis Riel.

It may seem strange to suggest that some new brand of Liberal-New Democrat coalition government, to replace and repair the (in some ways) over-centralized, militaristic, and crypto-authoritarian new Tory Family Compact minority government that Mr. Harper’s minority party has, by various devious means, now pretty much installed in the Ottawa wilderness, will finally appear as some 21st century successor to these near-great movements of progressive protest in the Canadian past. But, in our book at any rate, we are sadly very close to the point where this is, as they say down south, close enough for jazz.

Here’s hoping that this time the idea only slightly before its time will not in fact take quite as long as 11 years to reach its ultimate fruition.

[…] Canada today: Read more: Remembrance of coalitions passed … and the rebellion tradition in … […]

A very interesting and thoughtful article. Thank you. .My comment on Jack Layton relates to one of my goals in writing these articles: I don’t want our opponents to have the last word on what we did. Mr. Layton came in for some significant criticism from his Conservative opponents. I hold that in fact his conduct is much to his credit. All the best, Brian Topp.