Terrorism and human rights on trial : Melbourne 12 (and Toronto 18)

Apr 25th, 2010 | By Randall White | Category: Countries of the World

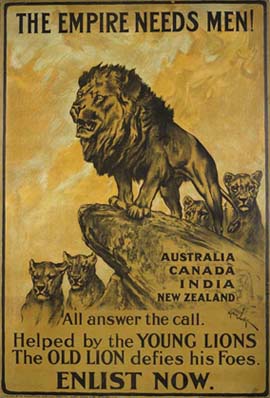

This UK Parliamentary Recruiting Committee poster urges men from the Dominions of the British Empire (and the South Asian Raj) to enlist for service in the First World War, 1914—1918.

Now that the final stages of the “Toronto 18” terror case are underway, a closely related package from down under has arrived in the mail.

It makes clear (yet again) that some striking similarities between the two former senior dominions of the fallen British Empire and Commonwealth remain, even if many early 21st century Australians and Canadians seem almost pathologically resolved to ignore each other.

The package contains a compelling DVD called The Trial, from 360 Degree Films. A website blurb explains how it tells the “inside story of Australia’s biggest terrorism trial … In February 2008 twelve Muslim men went on trial in Melbourne for terrorism offences. The trial ran for nine months, heard 482 secretly taped conversations and presented 66,000 pages of evidence. With unique access to Greg Barns, one of the key defence barristers, and Omar Merhi, the brother of the youngest accused, The Trial takes us inside one of the biggest court cases in Australia’s history. A trial where there is more at stake than just the fate of the accused.”

My first look at The Trial (the Australian product worked fine on my Canadian DVD player btw) prompted me to look into the Toronto 18 in somewhat more depth than I have before. The point of departure in both cases is the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the USAÂ – and the unprecedented breadth of the new anti-terror legislation that they stimulated in both Australia and Canada.

Greg Barns, dressed for court in an archaic outfit, he tells viewers of The Trial, that he would prefer not to have to wear.

The case of the “Melbourne 12,” so to speak, began in November 2005. It wound up, with final sentencing of convicted defendants, in February 2009. The Toronto 18 case started in June 2006. The last three defendants have only gone to trial just now, in the early spring of 2010.

As alluded to in the blurb for The Trial, the evidence in both cases is vast. I have now, I think, managed to get the lead characters straight in both the Melbourne 12 and Toronto 18 cases. But there is still much that I do not fully understand. Even so, my last viewing of The Trial (it is good enough for a second look, or more) reminded me that there are also some striking differences between Canada and Australia. And not all the advantages are on the Canadian side.

The “terrible incuriousness” that “infects Canadian public life …”

Saad Khalid, 19, in an undated photo, was one of those arrested June 2, 2006, in what Canadian police and security officials described as a home-grown terrorist ring. (Reuters).

As it happens, I have accidentally stumbled across a phrase that puts a more exact finger on my feelings here. On Friday 16 April 2010 – in a quite different context – Chris Selley at the National Post complained about the “terrible incuriousness” that “infects Canadian public life.”

I am ordinarily not a fan of Mr. Selley’s writing, and even less of the National Post. But his “terrible incuriousness” seems an apt description of my ultimate reaction to The Trial from Australia, and what it says about our parallel Toronto 18 terror case in Canada.

It may be that there is harder evidence of a practically serious and genuinely alarming plot to wreak havoc and death on large numbers of innocent ordinary citizens in the Toronto 18 case than there was in the case of the Melbourne 12. (That is a vague impression I have from the not entirely casual but still far from seriously in-depth digging I have been able to do in the time available: it may or may not stand up to further investigation.)

But even if this is true, I am finally struck by one key thrust of the message so robustly conveyed by The Trial, and conveniently summarized on the back of the DVD box from 360 Degree Films:

“Perhaps more important than the case itself The Trial explores the threat to our human rights posed by wide-ranging anti-terror laws. The defence team [which includes Greg Barns – a former John Howard government advisor who is far from any loony left, to adopt a locution from the old mother country – and two dozen other lawyers] argue that the threat of terrorism has been used by governments to extend the reach of the law into areas traditionally protected by the principles of freedom of speech and association. They believe that the laws themselves could pose a bigger threat to our democratic values than the threat of terrorism … ”

Whatever else may or may not be true, there has been too little of this kind of argument about the Toronto 18 terror case in Canada. I came away from my last look at The Trial feeling that this was not a good thing.

As the back of the DVD box also acknowledges, there is a “very real threat posed by terrorism” in many parts of the global village today, including Canada and Australia. Yet there are more than a few curious details about the Toronto 18. They deserve some form of fuller debate.

Here as elsewhere we need to do more about the “ terrible incuriousness” in Canadian public life, if we are ever going to live up to the ideals of the “free and democratic society” so impressively alluded to in our Constitution Act 1982 (which also begins “Whereas Canada is founded upon principles that recognize the supremacy of God and the rule of law.”)

The Trial – a somewhat closer comparative look

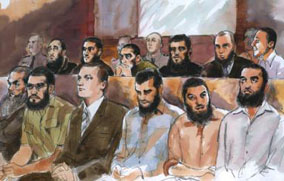

Artists’s impression of the 12 Melbourne men accused of being members of a terrorist organisation in court, August 2008. Illustration: Anne Spudvilas.

As best as I can make out, “Melbourne 12” is a term I have adopted, as an analogue for “Toronto 18.” The term is not used in The Trial nor in other sources on the Australian case.

Whatever you want to call it, the case of the Melbourne 12 has something behind it that is more or less missing from the case of the Toronto 18. This is the 12 October 2002 bombings in the tourist district of Kuta on the Indonesian island of Bali – which killed 202 people, including 88 Australians.

At the same time, it seems a fair guess that both the Australian and Canadian cases have been indirectly influenced, in one subtle way or another, by the 7 July 2005 London transit system bombings, back in the old mother country of the United Kingdom.

There was also a more modest reprise of the Bali bombings in Indonesia on 1 October 2005 – just a month or so before the initial terrorist arrests in Australia. In these 2005 Bali bombings four Australians died and 19 were injured. Three Canadians were injured as well.

Meanwhile, neither the Melbourne 12 nor Toronto 18 cases themselves involved events that have actually taken place. Both have prosecuted individuals for belonging to groups that have merely planned or talked about terrorist attacks, which have been aborted by public authorities before reaching fruition. Authorities have learned about these plans and this talk by listening in on “secretly recorded” conversations, technologically as it were, and, in the Toronto 18 case, via two human informants (or “moles”) as well.

In The Trial one key human rights issue here is summarized by demonstrators’ signs outside the Victoria state courthouse in which the Melbourne 12 case was heard: “TALK IS NOT A CRIME.” Yet what this DVD does so well is raise the dilemma of anti-terrorism laws that “themselves could pose a bigger threat to our democratic values than the threat of terrorism itself” in an adult way, which does not just evade all the attendant complexities.

“Maverick. Confrontationist. Hostile. Aggressive. And that's just his own description. Peter Faris, QC, delights in his ... political incorrectness” – and he spoke out against the defence team in the trial of the Melbourne 12. Photo: James Boddington.

The Trial does not pretend the kinds of anti-terrorism legislation that arose in places like Australia and Canada after the 9/11 disaster in the United States are just tragic bad jokes. It balances, eg, its footage of defence-team barrister Greg Barns and Omar Merhi, the brother of the youngest accused, with footage of Peter Faris, who co-hosts a weekly Australian public affairs TV show with Greg Barns, but altogether disagrees with him on the Melbourne 12 trial.

Faris urges that most Australians do not want to wait until 3,000 innocent victims have died in a terrorist attack that has actually happened, before prosecuting the terrorists. He concedes that this means criminalizing conduct which is not normally part of criminal law. But he urges that the Melbourne 12 are nonetheless being given a fair trial, based on a vast array of evidence, before a jury of their peers.

Whatever else, here is one key difference between the Canadian and Australian cases. The final stages of the “Toronto 18” case, involving the last three men accused, are taking place before a jury. Other defendants in Canada have just been tried before judges.

A few related comparisons are intriguing: in Australia all 12 defendants pleaded not guilty. (Although it also seems that a thirteenth Australian defendant had pleaded guilty in August 2007, and did not go to trial in February 2008.) In Canada six defendants pleaded guilty. The jury in Australia finally cleared four defendants of all charges, and was unable to reach a verdict in the case of a fifth, who was released on bail. In Canada the crown “stayed” or effectively dismissed the charges against seven defendants, who were then released from jail.

Emergency vehicles at Russell Square in London, just after the 7 July 2005 suicide bombings on the public transit system, that killed 52 people and injured about 700 more.

It is part of what The Trial is all about that it ultimately does stress the other side of the argument from Peter Faris – albeit without egregious exaggeration. Twice, near the beginning and then again near the end, Greg Barns urges that because of the “breathtaking scope” of the new anti-terrorism laws Australia enacted in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in the USA, it is “inevitable that there will be injustices” at some point in the administration of these laws.

One of Greg Barns’s colleagues on the defence team advances a related classic argument: “the right to say unpopular things is a right that we as Australians cherish.”

Barns also notes, as The Trial follows his work along, that, unlike the typical criminal case, there is virtually no dispute over the facts about the Melbourne 12. The authorities have many volumes of secretly taped conversations. No one is disputing that these conversations took place. The crucial argument is about what they mean.

The prosecutors claimed that the taped conversations mean there was an organized terrorist group to which the defendants belonged. This group planned attacks on such places as the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the Melbourne rail network, and a local casino. At the same time, Greg Barns’s particular client, Ezzit Raad, 26, an electrician, married with two children, “denied the existence of any group … and described its … [alleged] leader as nothing more than a friend.”

Along with six others Mr. Raad was nonetheless ultimately convicted by a jury of his peers – in his case “of being a member of a terrorist organisation, knowing that it was a terrorist organisation,” and “of intentionally making funds available to a terrorist organisation, knowing that it was a terrorist organisation.”

At Ezzit Raad’s sentencing hearing Greg Barns “said his client believed he had been convicted for what he thought rather than what he did and he believed the breadth of anti-terror legislation was to blame for his conviction.” Justice Bernard Bongiorno nonetheless “remarked that in one crucial conversation involving Ezzit Raad there was talk of raising money to obtain guns … on one view it revealed what the organisation hoped to become … it might never have achieved its ends but the prospect was ‘pretty frightening’.” And so Mr. Raad was finally sentenced to five years and nine months in jail.

[In Australia The Trial can be purchased online for AU$29.95. 360 Degree Films apparently also accepts international orders: see 360 Online Store … Terms and Conditions.]

Canadian footnotes: Michael Ignatieff on Isaiah Berlin … and Ujjal Dosanjh on “distorted multiculturalism” …

Michael Ignatieff (l) and Dr. Lamine Ba, President of the Africa Liberal Network and Vice President of Liberal International, at the 2009 Isaiah Berlin Lecture in London.

The main burden of The Trial’s underlying message from down under, one might say, is summarized in a classic American quotation, variously attributed to Benjamin Franklin and/or Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety” (Franklin) ; “Those who prefer security to liberty deserve to lose both” (Roosevelt, who may in fact have just been quoting Franklin?).

Two recent more or less Canadian variations on similar themes are worth noting quickly.

(1) Ignatieff and Berlin. In another universe, the current leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, Michael Ignatieff, is probably most celebrated for his biography of the late Isaiah Berlin – the “pre-eminent philosopher” of the “modern liberalism” that arguably lies at the centre of The Trial’s underlying message from down under. And, as a UK reviewer explained back in the late 1990s: “For Ignatieff, it is Berlin’s acceptance of the conflicting nature of human desire that makes him a truly great and humane thinker. For both men the human condition is tragic in the sense that the achievement of one aim always entails a loss somewhere else.”

From this angle, The Trial finally prompts us to ask ourselves, very seriously: if, in the midst of our tragic human condition, we really can have only one or the other of liberty or security, which are we going to choose? And, no doubt, if we do finally choose security, we are also (on Mr. Ignatieff’s and Mr. Berlin’s assumptions at any rate) effectively giving up on the liberal democratic tradition that has been one of the evolving great glories of the contemporary political culture in the United States, United Kingdom, France, India, Canada, Australia, and so forth. Or, as they say, if this is what we are going to do, the terrorists have already won.

Or, again, as Greg Barns argues in the closing segments of The Trial, the breathtakingly broad definitions of criminality that have been adopted in the anti-terror legislation at the bottom of the case of the Melbourne 12 (or the Toronto 18) could ultimately be applied to individuals who, eg, merely talk about threatening peaceful labour relations, as well as so-called Islamic extremists who merely talk about waging jihad against innocent ordinary citizens of democratic countries.

The Trial does not point out that fewer people died in the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States than die in a single month of automobile accidents on American highways. But this too is a simple truth. How much real safety or security can any government anywhere ever guarantee its citizens? (Or, how seriously does anyone nowadays take the stunningly brave motto that still haunts New Hampshire licence plates in the USA: “Live free or die”?)

(2) Ujjal Dosanjh: a Canadian liberal Sikh. On the other hand, just because Michael Ignatieff and Isaiah Berlin believe something about liberal democracy does not necessarily make it true for the rest of us, all of the time. Recent Canadian events have made clear that Islamic extremism is not the only contemporary terrorist threat. There is such a thing as “Sikh extremism” or terrorism abroad in the true north, strong and free (in both suburban/exurban Vancouver on the Pacific Coast and suburban/exurban Toronto on the Great Lakes).

Federal Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Vancouver South, Ujjal Dosanjh (l), at a meeting on gang violence at South Vancouver Neighbourhood House, March 18, 2009. He is meeting Jodie Emery, wife of Canada’s “Prince of Pot,” Marc Emery. Photo by Sen.

Ujjal Dosanjh, a former federal Liberal cabinet minister and onetime New Democrat premier of British Columbia – and, as it were, a liberal Sikh “who was savagely beaten in Vancouver in 1985 after speaking out against religious violence” –Â has lately had some compelling things to say about all this.

I can do no better than quote from a recent article in the Globe and Mail, “‘Distorted’ multiculturalism to blame for rise in Sikh extremism, Dosanjh says … Liberal MP argues militancy is worse now than when bomb destroyed Air India plane, killing all 329 aboard.” And it is, I think, intriguing – and instructive – that Mr. Dosanjh is not arguing here that we need more anti-terrorism legislation in Canada. Instead, as best as I can make out, he is finally arguing that we need more of the liberal democratic values that constitute the main burden of The Trial’s underlying message from down under.

Listen carefully, eg, to this: “Mr. Dosanjh blamed what he described as Canada’s polite brand of multiculturalism for giving extremists the space to nurture old grudges brought from their homelands. At the same time, Canada has failed to instill its own values … ‘I think what we are doing to this country is that this idea of multiculturalism has been completely distorted, turned on its head to essentially claim that anything anyone believes — no matter how ridiculous and outrageous it might be — is okay and acceptable in the name of diversity … Where we have gone wrong in this pursuit of multiculturalism is that there is no adherence to core values, the core Canadian values … That you don’t threaten people who differ with you; you don’t go attack them personally; you don’t terrorize the populace.”

The Globe and Mail article went on: “Mr. Dosanjh urged mainstream Canadians who aren’t part of these ethnic communities to step up and speak against extremism … ‘I think Canadians need to engage in this cultural diversity debate,’ he said … ‘We should stop being politically correct and have a debate.’”

Or, one might say (or so it seems to me), if you finally want security, you have to take up the challenge and discipline of liberty head on. Liberty and security are not always two mutually exclusive achievements. Mr. Ignatieff and Mr. Berlin notwithstanding, perhaps in the very end they can only be achieved together.

Or, yet again, in Canada we somehow have to cast aside the “terrible incuriousness” that “infects Canadian public life,” and stand up more boldly for what we really do believe in. It is this kind of more aggressive assertion of our core values – and not more terrorism trials that can only pervert those values, however well-intentioned the motivations behind the trials may be – that will finally save us from all the fearsome terrorist challenges which stalk the global village today. And in this context what The Trial from down under is ultimately reminding us is simple enough: we will finally keep our freedom only by living free.

In Canada today all this assumes some particular interest, in the light of some very recent press reports on how federal “Justice Minister Rob Nicholson announced Friday [April 23, 2010] that his party would seek to pass a Combatting Terrorism Act that would revive some urgent powers. In dire cases, police could temporarily hold terrorism suspects without charge, and judges could compel testimony from individuals who may know about attacks, past or planned … These emergency powers existed in Canada for several years after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on New York and Washington, but were never used. Parliament voted to repeal them in 2007, against the minority Conservatives’ wishes … It’s unclear whether the Tories could pass the new act before the next election. Similar attempts at revival have died before … The terrorism law plays to the Conservatives’ law-and-order base and puts the Liberals in a difficult position.”

Critical perspectives on the Toronto 18 terror case

Zakaria Amara, said to be the mastermind of “a bomb plot in downtown Toronto” at the centre of the Toronto 18 case, was finally sentenced to life in prison as a “message of deterence.” He had apologized to Canadian citizens at his sentencing hearing, and while acknowledging that most Canadians would never forgive him, expressed hope that he might one day redeem himself.

Before I end the main body of this already far too long review of an unusually interesting recent Australian DVD, I want to close with a few minor qualifications on my urgings about the unhappy dearth of The Trial’s kind of argument about the Toronto 18 terror case in Canada.

I continue to think my point here is essentially correct. (And if I am essentially wrong, I would be more than happy to hear more about it.) Various groups and individuals in Canada, however, have tried to bring some critical perspective to bear on the trials and tribulations of the Toronto 18. And I want to quickly give some credit where credit is due.

As best as I can make out from my all too hasty adventures on the net, the leading critical analyst of the Toronto 18 has probably been Thomas Walkom at the Toronto Star. His articles include: 25 Sep 2007:Â Terror trial proceedings troubling … Bizarre allegations about Toronto 18, unorthodox decisions are raising questions about Crown’s case ; 8 Nov 2007: Confusion, despair from terror suspect isolated in Don Jail ; 26 Sep 2008: Terror verdict bad news for rest of Toronto 18 ; 13 Sep 2009: Opaque verdict on terror laws ; and 27 Jan 2010: Judge ponders police tactics.

Mr. Walkom’s efforts have received some critical attention in their own right, from the other side of some ideological divide See, eg: The Gospel According to Saint Lefty … Toronto 18 …Â The Terrorist Comedy Hour With Host, Thomas Walkom.

Beyond Mr. Walkom’s exertions, see as well: Toronto 18 – Petition to end solitary confinement! ; Articles tagged with Toronto 18:Â faisal kutty.com ; 25 Nov 2008: Lawyer Faisal Kutty speaks on Civil Liberties in Canada ; and 4 Nov 2009: TORONTO STAR EDITORIAL: Spy chief sings the blues.

Finally, there is “an independent documentary released in 2008 … by Canadian broadcaster David Weingarten.” It is called Unfair Dealing and “was originally marketed to an online audience.” It “alleges that the terrorism charges brought against the ‘Toronto 18′ were largely exaggerated or fabricated by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) in order to justify the controversial Canadian Anti-Terrorism Act …” Judging from what I have seen of it on YouTube, Unfair Dealing does not achieve at all the same kind of adult presentation of the issues at stake as The Trial in Australia. It does nonetheless offer some critical perspective on the Toronto 18.

Appendix: The “Toronto 18”

When I first looked at The Trial on my TV set, via my Canadian video player (well, sold in Canada at any rate), I was only vaguely aware of the analogous Toronto 18 case (like many other Canadians no doubt).

I subsequently felt an urge to learn more about the Toronto 18, to better appreciate the case of the Melbourne 12. I am appending the rough and ready results of my rather hasty research here, in case it may somehow be useful to anyone else suddenly seized by similar urges.

To set the stage, in the summer of 2006, police carried out a massive anti-terrorism sweep in southern Ontario. Seventeen people – 13 adults and four youths – were arrested in a series of June raids.

More exactly, on June 2Â police arrested 10 men and five youths. Two other suspects were already incarcerated in Kingston, Ontario. An 18th individual was detained two months later.

1. The four youths arrested in June 2006

The four youths could not be named under the Youth Criminal Justice Act. But their ultimate disposition was as follows:

Charges stayed against three youths

(1) 23 Feb 2007: Charges against the youngest suspect are stayed. The 16-year-old from Mississauga, who cannot be named under the Youth Criminal Justice Act, was originally granted bail in July 2006.

(2), (3) 31 Jul 2007: Charges are stayed against two other youths in connection with the bust. The decision comes after an agreement is reached between the Crown and defence lawyers.

Fourth youth becomes first person found guilty under post 9/11 terrorism laws

(4) 25 Sep 2008: An Ontario Superior Court judge convicts the first of 11 men accused in the alleged plot to bomb several Canadian targets, including Parliament Hill, RCMP headquarters and nuclear power plants … The accused, who is charged as a youth and therefore cannot be identified under the Youth Criminal Justice Act, is found guilty of participating in a terrorist activity. He also becomes the first person in Canada to be convicted under federal anti-terror legislation passed in 2001 … In his ruling, Judge John Sproat says evidence that a terrorist conspiracy existed was “overwhelming” … It subsequently becomes known that this youth’s name is Nishanthan Yogakrishnan. On 22 May 2009 he was sentenced as an adult to two and a half years of time served. Again, he was the first person to be found guilty under Canada’s 2001 Anti-Terrorism Act, which was passed following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. He walks free hours after his sentencing hearing, because the judge ruled he’d already served enough time in custody.

2. The 18th individual detained in August 2006

3 Aug 2006: Police arrest Ibrahim Alkhalel Mohammed Aboud, 19, at his home in Mississauga, Ont., in connection with the alleged bomb plot. Aboud’s arrest is the first in the case since the sweep in early June.

3. Charges stayed against four adults

(5), (6), (7), (8) 15 Apr 2008: In a surprising development, Crown prosecutors ask for a stay of proceedings against four suspects – Ibrahim Aboud [see above], Ahmad Mustafa Ghany, Abdul Qayyum Jamal, and Yasim Mohamed.

Along with the three unnamed youths against whom charges have earlier been stayed, this means that a total of seven people have had “their charges dropped or stayed.”

4. First adult to plead guilty

(9) 4 May 2009: Saad Khalid, 22, pleads guilty to a charge of intending to cause an explosion … The case is set over to June when the judge will hear evidence on information behind the guilty plea … Khalid is the first adult from the group arrested in the summer of 2006 on suspicion of terrorism to admit to playing a role in the alleged plot.

3 Sep 2009: Saad Khalid, 23, is sentenced to 14 years in prison after pleading guilty to a charge of intending to cause an explosion. Khalid was credited with seven years for time already served, for the 39 months in pre-trial custody. He had seven more years to serve as of last September, and should be free when he is 30 years old.

5. Three more adults plead guilty

(10) 21 Sep 2009: Ali Mohamed Dirie, 26 pleads guilty to one count of participating in the activities of a terrorist group. Both Crown and defence ask the judge to give Dirie a seven-year sentence, but differ on how much credit he should be granted for time served.

(11) 27 Sep 2009: Saad Gaya, 21, pleads guilty to intentionally trying to cause an explosion for a terrorist group. At the time of his arrest in June 2006, Gaya was a high school honour student.

2 Oct 2009: Ali Dirie, 26, is sentenced to seven years in prison and, after allowances for time already served, will spend two more years in custody. He will have to serve at least one year before he can apply for parole.

(12) 8 Oct 2009: Zakaria Amara pleads guilty to charges of knowingly participating in a terrorist group and intending to cause an explosion for the benefit of a terrorist group … Amara, 24, has been accused of being one of the ringleaders in the alleged plot.

18 Jan 2010: Saad Gaya, 22, is sentenced to 12 years in prison. Gaya, described by the judge as a mere “helper” in a plot, has been in custody since his 2006 arrest. With credit for time already served, Gaya is sentenced to another 4½ years, but may be eligible for parole by mid-2011.

18 Jan 2010: Zakaria Amara, described as the main organizer of the plot, is sentenced to life in prison. Judge Bruce Durno calls the sentence a message of deterrence to society and says if the plan had been successful, “it would have terrorized Canadian society and killed many.”

6. First adult charged to stand trial

(13) 11 Jan 2010: Shareef Abdelhaleem, 34, the first adult charged in the plot to stand trial, pleads not guilty to charges of participating in a terrorist group and intending to cause an explosion.

21 January 2010 … Shareef Abdelhaleem found guilty of plotting to bomb financial, intelligence, and military targets. He also sought to profit financially from his terrorism. He was not convicted right away, however, as his defence was awarded a stay of proceedings to look into whether or not the case could be considered as entrapment.

16 February 2010 … A judge determines that Shareef Abdelhaleem was not entrapped by authorities, as his counsel had suggested.

7. Two more adults plead guilty

(14) 20 Jan 2010 … Amin Mohamed Durrani pleads guilty to charges of participating in a terrorist group. Durrani was sentenced to 7½ years in prison, but taking into account time he has already spent in custody, he was expected to be released within days.

(15) 27 Feb 2010 …Â Jahmaal James pleads guilty to one count of participating in a terrorist group and is sentenced to seven years. He is released immediately due to time served and put on three years of probation

8. Last three go to trial

(16), (17), (18) 22 Mar 2010 … Last three defendants in Toronto 18 terror case go to trial … one of the largest terrorism trials in Canadian history …Â trial … could last up to two months … Fahim Ahmad, Asad Ansari, and Steven Chand have been awaiting trial since June 2, 2006, when they were among 14 adults and four youths charged with belonging to a cell plotting a terror attack on Canada, in retaliation for its military involvement in Afghanistan.

A FEW KEY SOURCES:

2006 Toronto terrorism case … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia [not one of the better Wikipedia products, but of some use if treated with care and caution].

20 Jan 2010 … ‘Toronto 18’ case: Key events [from the CBC – and the single most useful source today?].

27 January 2010 … Judge ponders police tactics … Thomas Walkom.

16 February 2010 … Toronto 18 conspirator Shareef Abdelhaleem not entrapped: judge.

21 Mar 2010 … Last 3 in Toronto 18 terror case go to trial.

12 Apr 2010 … Attacking Parliament, devastating Canada at heart of Toronto 18 plot, jury hears.

Shareef Abdelhaleem … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Jahmaal James … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

[The Canadian film] unfair dealing is not credible at all because the overwhelming majority of its assertions are unproven (at the time of their making) and speculative. Since its production, several accused plead guilty, 1 was found guilty by judge – the others who had charges stayed were not found ‘not guilty’ or acquitted. It is more reasonable to suggest that they were involved in some way but probably not to the level that a full prosecution would have to sustain. take it as money and time saved but the point needed to be made to the public – Muslim wannabe’s especially.

The fact is, both the Melbourne 12 and T18 were real threats. terror plots develop in stages and the end result is a terrorist attack on the public. it would be devestating to conduct anti terror operations starting from the attack first. nor should every attempt by authorities to deal with terrorism, be taken as being synonymous with the erosion of rights. it is due to those efforts of the authorities that we have the safety and security to enjoy the rights we have. enough with the rhetoric – there are no secret camps waiting for everybody – no secret trials … these were open and very fair proceedings.

As I note in my review above, in my own view the Canadian film “Unfair Dealing does not achieve at all the same kind of adult presentation of the issues at stake as The Trial in Australia.” So I’d agree with Zebra on this, in part at least.

As for Zebra’s other comments, I don’t think what’s seriously at stake here has anything to do with rhetoric. I’d just repeat something I noted in response to another comment on the short pointing piece to my review of the Melbourne 12 film on this site. Viz., the essential argument of The Trial from Australia was nicely summarized, I think, in a piece by Ms. Marni Soupcoff in a recent issue of the National Post (almost certainly Canada’s strongest law-and-order newspaper), on our federal government’s current plan to reinstate two contentious provisions of Canada’s anti-terror legislation: “The government should continue to fight terrorism aggressively and relentlessly. But it should do so by using its normal police, intelligence and investigative powers; not by changing the laws to make our country less free and democratic — our attackers’ very own aims … Otherwise, the war on terror is hardly a war worth winning.â€

http://network.nationalpost.com/NP/blogs/fullcomment/archive/2010/04/27/marni-soupcoff-police-don-t-need-more-power.aspx

Looks like the Toronto trial has concluded. Information previously restricted, conditions which gave rise to the critical voices, can be accessed at:

http://www3.thestar.com/static/toronto18/index.html

It looks extremely well done if I may say so. I followed both these cases with great interest and The Trial is well put together. Kudos to those involved.

Thanks for the great article, I really enjoyed your analysis of “The Trial”. Though I haven’t had a chance to view “The Trial”, I know from my own research that there are definitely some disturbing similarities between the Melbourne case and the Toronto 18. This includes the criminalization of thought, the prosecution of free speech, and the use of informants to facilitate a crime.

I happen to be the producer of “Unfair Dealing”, and though I appreciate your critique of the video, I think for what it lacks an “adult presentation” may be the wrong choice of words. Though the film is regrettably too cursory an examination for such a complex case, it has been warmly received internationally despite a severe lack of funding. And though “Zebra” and some others take issue with the fact that our assertions were unproven at the time of production, we take great pride in the fact that these “assertions” have now been proven correct.

Releasing seven suspects, including a reported “ringleader”, certainly shatters the impression given by the RCMP and media that this was a single, cohesive and determined group of 18 terrorists plotting havoc. Among those seven include winter campers who were ordered to be kept “on the down-low” about any sinister nature of the camping trip. Authorities knew most of these campers were clueless, but arrested them anyway and labeled them as “terrorists” to the public – some of them in their early teens.

Even some of the convicted suspects, by any stretch, are not “terrorists”. The first to be convicted, Nishanthan Yogakrishnan, had been so because he stole walkie-talkies (without any knowledge of a terror plot). Two more of the convicted suspects are “innocent”, according to the very informant who infiltrated them.

When you get down to the core group of 4 or 5 who actually had the intent to cause damage, it’s clear that they were inept, and only able to carry out their actions with the assistance of paid informants playing crucial roles. One informant was brought in for the explicit purpose of “dangling” his agricultural sciences degree, and then telling the suspects they could not back out once the fertilizer deal was initiated. This informant, according to CSIS, was motivated by “money” and “spite” toward one of the suspects with whom he had a previous, bitter relationship.

If you’re wondering where the suspects got the idea for fertilizer bombs, it was from a different mystery-man named Qari Kifayatullah, who was never arrested. Despite talking about fertilizer bombs with suspects in a high-profile terrorism case, Kifayatullah was last reported to be a free man, working as a volunteer for the UN in Afghanistan. It raises questions as to how many informants were actually used, and what roles they played.

There are many areas of “Unfair Dealing” we would have wanted to provide more detail on. It is a shame however, that funding and government secrecy can hamper that. You might say a film like “Unfair Dealing” can leave the prophet between two stools. Too little information and the film is worthless. But waiting until all classified information is released can result in a very accurate, detailed account that is simply too late. By that point, as we’ve seen in the “Toronto 18”, years will have passed and the government will have already deeply impressed on the public whatever story they want, even if it is mostly wrong. What we did was take the available information in the media, and extrapolate it according to previous cases of homegrown terrorism involving informants and explosives. Think London 7/7, Fort Dix, the Newburgh 4, etc.

To address whether or not these young men were a real threat, you might want to refer to comments by David Charters, who was a member of Stephen Harper’s Advisory Council on National Security. This man, obviously an expert in his field, has dubbed the “Toronto 18” as jihadi wannabees, who he thought would not be found guilty of any serious crimes.

We would simply hope that people use this film as a starting point to research the Toronto 18, and appreciate that it was successful in demonstrating that these arrests were largely exaggerated or fabricated, at a very sensitive time in Canadian politics no less.

We should have an extremely detailed account of the case online in the form of a timeline later this week. Check out http://www.weingarten.ca or fortress-toronto.com soon and it should be up. Again, nice work on the article. Take care.

http://fortress-toronto.com/toronto-18-timeline.html