A tale of two reviews of books : on the memory loops of George W. Bush

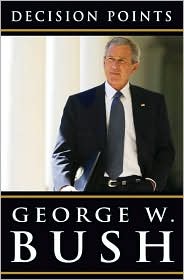

Jan 7th, 2011 | By Randall White | Category: USA TodayApparently George W. Bush’s presidential memoir, Decision Points, only released this past November 9, 2010, has already “sold almost a million and a half copies.”

According to one wise observer, it is nonetheless “unlikely that many will ever read Decision Points, and even fewer will finish it … Conservative groups buy these things in bulk … Moreover, in the mere two years since he left Washington, Bush is beginning to seem like a reasonable man compared to the Republicans who have now been elected to higher office.” (Up here in the northern woods, another attraction may be that you can obtain a hardcover copy from Amazon Canada for 50% off – or a mere C$19.97!)

I have not read or even purchased the book myself, and have no intention of ever doing so. Thanks to the miracle of the Internet, however, I have just finished reading two reviews of the thing, available for free online in the current issues of the London Review of Books and the New York Review of Books.

Both are by American writers. Neither presents an even inexactly enthusiastic report. Yet the reviewers are from related but different backgrounds. And they do provide different reviews, each of which says something interesting about the USA today. I can recommend both pieces wholeheartedly, back to back.

Both are by American writers. Neither presents an even inexactly enthusiastic report. Yet the reviewers are from related but different backgrounds. And they do provide different reviews, each of which says something interesting about the USA today. I can recommend both pieces wholeheartedly, back to back.

The one I read first is by Eliot Weinberger, in the 6 January 2011 issue of the London Review. Weinberger was born in 1949 in New York City, where he still lives. He first became well-known as a translator of the Mexican poet and diplomat, Octavio Paz. He is now “primarily known for his literary writings … and political articles, the former characterized by their experimental style … and the latter highly critical of American politics and foreign policy.”

Weinberger’s review of Decision Points starts with a witty allusion to the French philosopher Michel Foucault (that also has “George Bush Jr … at Yale, branding the asses of pledges to the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity with a hot coathanger”), carries on in a snidely entertaining way (that many, including myself, will feel well suited to the subject), and has almost nothing at all redeeming to say about either Decision Points or George W. Bush.

Joseph Lelyveld, winner of the 2001 Burton Benjamin Memorial Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists.

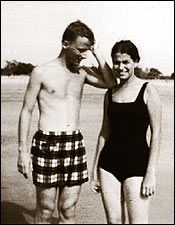

My second piece, by Joseph Lelyveld, appears in the January 13, 2011 issue of the New York Review. Born in 1937, Lelyveld spent his earliest years in Omaha, Nebraska, but then moved with his family to New York City. He had a long and widely travelled career with the New York Times, culminating with a memorable tenure as executive editor of the paper from 1994 to 2001 (and then on an interim basis briefly again in 2003).

Lelyveld’s review of Decision Points is more sober than Weinberger’s – and not as openly witty and amusing. He also tries now and then to give George W. Bush some fair-minded credit for something. Yet a few years ago a magazine article explained: “As a writer, Lelyveld has always been a master at summoning moral outrage without resorting to outrageous language.” And this talent is on display in his review of Decision Points. Towards the end he notes that the second former President Bush “underscores a few instances in which he overruled [former Vice-President Dick] Cheney … but otherwise sheds little light on how their relationship actually worked. Does he know even now?

* * * *

The best thing I can do with these two reviews, I think, is just encourage others to read them – for free on the net. If I had it to do again myself, I think I would reverse the order in which I came across them. I’d start with Lelyveld, and then finish with Weinberger.

There are a few further quick notes I can make myself, especially for those who want to end their study of the matter right here.

There is, eg, the intriguing question of exactly who has written Decision Points. Lelyveld more or less sticks with the polite fiction that the author is the George W. Bush of official record, with only some of the usual suspects: And: “When we consider that he left the White House in the midst of two wars and the worst financial collapse in eight decades, it’s no small feat that he (along with a former speechwriter named Chris Michel who assisted him) manages to sustain his sense of himself as a decisive, well-meaning commander in chief in a time of crisis.”

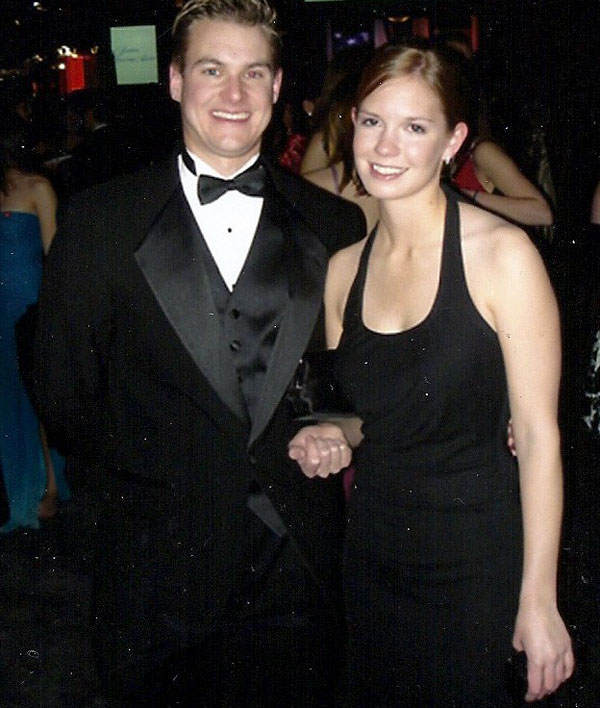

The young White House prodigy Chris Michel and his future wife Emily at the 2005 inauguration of George W. Bush : he would soon become a key speech writer for the president, and then a key assistant and/or ghost-writer on the presidential memoirs.

On this same question, Weinberger is more amusing, sarcastic, and sceptical, and conceivably closer to the rawest truth: “Decision Points holds the same relation to George W. Bush as a line of fashion accessories or a perfume does to the movie star that bears its name; he no doubt served in some advisory capacity. The words themselves have been assembled by Chris Michel (the young speechwriter and devoted acolyte who went to Yale with Bush’s daughter Barbara); a freelance editor, Sean Desmond; the staff at Crown Publishing (who reportedly paid $7 million for the book); a team of a dozen researchers; and scores of ‘trusted friends’.”

Both reviewers stress that the book is remarkable as much (or more) for what it leaves out as for what it puts in. The comparative dearth of attention to the President’s Vice-President is cited as a key case in point. The preamble to Lelyveld’s remarks on Dick Cheney noted above goes: “In Cheney’s case, he [ie the authorial presence George W.] treats as laughable the idea that this most powerful vice-president in history was functioning more as a prime minister than an adviser. But he says little to suggest that he was fully aware of the manner in which Cheney’s office had seized control over national security debates …Â ‘One myth was that Dick was actually running the White House,’ he writes. ‘Everyone inside the building, including the vice president, knew that was not true.’”

Weinberger’s observations on the same subject are characteristically more brash: “The enormous black hole in the book is the Grand Puppetmaster himself, Dick Cheney, the man who was prime minister to Bush’s figurehead president. In Decision Points, as in the Bush years, he is nearly always hiding in an undisclosed location. When he does show up on scattered pages, he is merely another member of the Bush team. The implicit message is that Washington was too small a town for two Deciders … Only twice in this fat book does one get a sense of Cheney’s presence.”

Joe Lelyveld and his wife Carolyn in Moulmein, Burma, 1961. Carolyn, who he had met at high school in the Bronx and with whom he was very close, sadly died of cancer in 2004. Photo: Courtesy of Joseph Lelyveld/Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

I will end on two more quick notes. To start with, Lelyveld observes that another surprisingly “minor character” in Decision Points is Karl Rove. And Weinberger reports that if, like Karl Rove and others you might have expected to see more of, Dick Cheney’s appearances are far and few between: “Unexpectedly, Dad is everywhere in the book, with father and son continually declaring their mutual pride and undying love.” Yet another ubiquitous family member seems more formidably critical: “Mother – she’s never Mom – pops up frequently with a withering remark. As middle-aged Junior runs a marathon, Mother and Dad are, of course, coming out of church. Standing on the steps, Dad cheers ‘That’s my boy!’ and Mother shouts ‘Keep moving, George! There are some fat people ahead of you!’”

A final collateral pleasure for me in my encounter with these two reviews of the world according to George W. Bush turned around at least slightly increasing my limited northern wilderness acquaintance with the career of Joseph Lelyveld – “the most powerful man in journalism” (well US or even just New York journalism at any rate), at the height of his career at the New York Times. Understanding a little more about him helps you understand a little more about his review of Decision Points, and why it is rather different from Eliot Weinberger’s. (Apart from the obvious facts that Weinberger is a dozen years younger, and a literary flaneur who reads poetry in public rather than a former most powerful man in journalism.)

Joe Lelyveld of The New York Review of Books and Jill Abramson of The New York Times at the Vanity Fair-Google Party, September 2008.

For those who may also want to dig a bit deeper into the Lelyveld persona, one good place to start is a 2005 New York magazine profile by Stephen J. Dubner called “The Scoop of His Life.” A useful supplement is a Charlie Rose interview from the same year – which offers the man in person as a talking head, at the age of 68. (He is now 73.)

The occasion for both these pieces was the 2005 publication of Lelyveld’s autobiographical book, Omaha Blues: A Memory Loop. And in the Charlie Rose interview he explains that he chose the term “memory loop” rather than “memoir,” because “I am telling not the story of my life but rather a story of my life … To me there is a difference.” The same characterization, it would seem, could be justly applied to Decision Points – which is just a story of part of the life of George W. Bush. Some day someone else may write the biography of his turning-point presidency that the American people deserve.