Why John A. Macdonald can never be Canada’s George Washington

Jan 17th, 2011 | By Randall White | Category: Ottawa Scene This past Tuesday, January 11, was John A. Macdonald’s birthday (and, intriguingly enough, also Jean Chrétien’s).

This past Tuesday, January 11, was John A. Macdonald’s birthday (and, intriguingly enough, also Jean Chrétien’s).

Macdonald, in case you’ve forgotten (as almost half those Canadians consulted in a 2001 survey had) was the first prime minister of the present confederation in Canada – and remains “the only Canadian Prime Minister to win six majority governments” (1867,1872, 1878, 1882, 1887, 1891). For certain Canadians at least, he deserves more recognition in Canada today than he usually receives.

As just one case in point, a “group in his hometown of Kingston, [Ontario] spearheaded by historian Arthur Milnes, wants the bicentennial of Sir John A.’s birth to be a national celebration. And it’s only four years away.”

Yet when you look just a little deeper into the past and present of the most northern regions of North America, it is not too hard to understand why John A. Macdonald remains less than the “George Washington of Canada” that some still yearn for in vain.

This past Tuesday as well, eg, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued a formal written statement “in recognition of Sir John A. Macdonald Day.” (The Macdonald enthusiasts have not been entirely unsuccessful in their campaigns. They did manage to get an Act of Parliament declaring January 11 to be Sir John A. Macdonald Day. It “came into effect in March 2002.”)

But Prime Minister Harper’s statement this year was quite brief, circumspect, bereft of any bold founding father rhetoric, or even slight hints of serious admiration. And it was accompanied by a photograph of Mr. Harper standing beneath the official Macdonald portrait in the Ottawa Parliament Buildings – in which the present prime minister of Canada looks distinctly uncomfortable and ill at ease.

1. Macdonald Conservatives and Harper Conservatives

Two recent newspaper articles help explain the strange look on Mr. Harper’s face as he stands beneath John A. Macdonald’s official portrait (presumably at the behest of some bright but shallow operative in the PMO?).

You might think that Macdonald was a Conservative and so is Harper: they should have a lot in common. But especially in Canada there are Conservatives, and then there are Conservatives. Consider a piece this past week by Conservative Senator Hugh Segal in the Sudbury Star and Kingston Whig Standard. “Sir John A. Macdonald Day,” Senator Segal writes is “the time to consider and celebrate the distinctly Canadian brand of conservatism he bequeathed Canadians.”

Note, eg, “a letter Sir John A. wrote to a supporter 13 years before Confederation: ‘Our aim should be to enlarge the bounds of our party as to embrace every person desirous of being counted as “progressive conservative” … of more reactionary and narrow Tories, Macdonald said they had ‘little ability, no political principles and no strength in numbers.’”

Stephen Harper in office, some might argue, is a lot closer to this Macdonald-style progressive conservatism than he was in opposition (at least as the leader of two successive minority governments). But, others will quickly urge, this is not where his heart lies – or where he will go if he ever does win a majority government.

It is similarly notable that the official name of John A. Macdonald’s party was actually “Liberal Conservative.” And an article by the Kingston historian and Macdonald bicentennial activist, Arthur Milnes, in the January 11 Toronto Star, underlines the continuing relevance of this 19th century label.

As Mr. Milnes reports, Tom Van Dusen, a former executive assistant to John Diefenbaker, once said to Pierre Trudeau “I always suspected, Prime Minister, that you were a Conservative at heart.” And the late 20th century Liberal prime minister who had so much to do with Canada’s new Constitution Act 1982 replied: “I am. A Sir John A. Macdonald Conservative!”

Whatever else, it seems clear enough, Stephen Harper still hates Liberals, and still has no use for the political philosophy of Pierre Trudeau. Late at night in the dead of the Ottawa winter, Mr. Harper knows that he is not a progressive conservative or a Liberal Conservative or a John A. Macdonald Conservative – or anything like that at all.

(Or, to quote someone who knew him personally, way back when, from another recent article in the Globe and Mail: “To be blunt, Mr. Harper’s ultimate strategic goal really isn’t to win a majority government – it’s to eradicate the Liberal Party as a viable political force.”)

2. The federal government’s role in the Canadian federation

Trudeau’s declaration that he was a John A. Macdonald Conservative also signals what many will see as a centralizing attitude to the Canadian confederation – or at least a concern for the strength of the federal government – that further helps explain why Stephen Harper seems uncomfortable beneath Macdonald’s portrait.

Mr. Harper, even as a prime minister of two successive minority governments, believes in a more decentralized Canada than either John A. Macdonald or Pierre Trudeau.

Or as Jeffrey Simpson wrote last month in a column about “Big” and “Little” Canada: “Let’s remember that Ted Morton, Alberta’s Finance Minister, used to argue that Alberta should withdraw from the CPP [Canada Pension Plan] and create its own plan [like Quebec already has]. He, with now-Prime Minister Stephen Harper, was also one of the authors of the infamous ‘firewall’ letter that urged Alberta to defend itself against federal incursions and intrusions.”

In fact, the National Energy Policy fiasco of the early 1980s has given Trudeau something of an undeserved bad name as an over-ardent centralizer in Canadian federalism, who lacked respect for regional interests. No politician from Quebec could be as centralist as John A. Macdonald (who was that way, perhaps, partly because he had such a keen appreciation of the “natural” tendencies towards decentralization in any Canadian federation, from coast to coast to coast).

Paul Hellyer from Ontario actually left Trudeau’s first cabinet in 1969 because he finally felt the new prime minister from Quebec had too decentralist a view of the federation and the role of the federal government in Ottawa (with special reference to national housing policy).

At the same time, it is not at all easy – based on the past five years and the 10 before that – to imagine Stephen Harper standing up for a strong federal government as well as strong provincial governments, as Pierre Trudeau did during the constitutional debates that followed the Quebec sovereignty referendum of 1980, when he poignantly asked whoever would listen, again and again: “Who will speak for Canada?”

3. The man who hanged Louis Riel … then and especially now

Even setting progressive conservatism and abstract concepts of centralization in Canadian federalism aside, while there is much to admire and appreciate (and even enjoy) in the unique political career of John A. Macdonald, he certainly was not and cannot be any kind of George-Washington-like founding father of Canada. And that may have as much as anything else to do with his comparatively low profile in the Canadian popular imagination today.

On one strand of the argument here as well, today’s Prime Minister Harper and not yesterday’s Prime Minister Macdonald is on the side of the angels – regardless of what we may think about Stephen Harper and his early 21st century Conservative Party of Canada in other contexts. (And I should confess that I don’t like it much myself.)

To make a long story very short, among other things John A. Macdonald lives on in one Canadian popular legend as the man who “hanged Louis Riel,” in the wake of the Northwest Rebellion of 1885.

At first, this hurt Macdonald’s reputation in Quebec – a dozen years after the death of his historic confederation era partner from French-speaking Montreal, George-Étienne Cartier. (In the midst of various appeals following Riel’s conviction for treason Macdonald is sometimes reputed to have declared “He shall hang though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour,” though the Canadian political historian P.B. Waite notes that hard evidence for anything Macdonald said on Riel at the time “tends to be thin.”)

It similarly seems quite arguable that the history of the federal Liberals as the “natural governing party of Canada,” in the 20th century at least, begins with the Macdonald Conservatives’ hanging of Louis Riel on November 16, 1885. And it is intriguing that when Pierre Trudeau became Liberal Prime Minister of Canada in 1968, he moved not into John A. Macdonald’s old office in the East Bloc of the Parliament Buildings, like all his predecessors, but into the adjacent office that George-Étienne Cartier had occupied, from 1867 to his death in 1873.

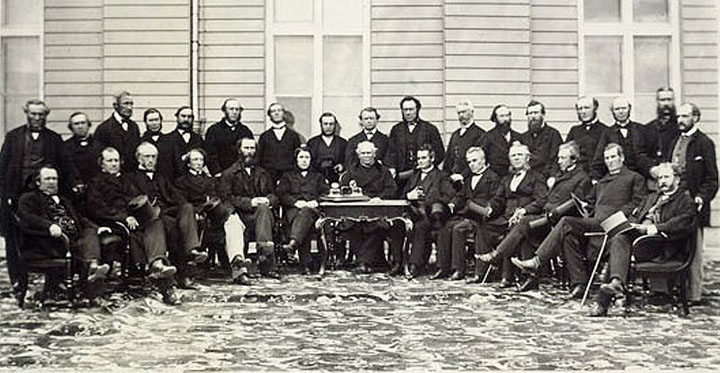

At the Quebec conference on the road to confederation, October 27, 1864. Macdonald is fourth from the left in the front row. Cartier is fifth from the right.

More recently, and especially in our own time, Louis Riel has also become a hero of English-speaking regionalism in Western Canada. And the John A. Macdonald who is said to have hanged Riel has become the historic inventor of the Ontario-Quebec/Central Canadian imperialism that tyrannized over the development of Atlantic, Northern, and especially Western Canada, in the narrow self-serving interests of the so-called Montreal-Ottawa-Toronto triangle.

Macdonald may not deserve all the regionalist vitriol that has come his way in the most recent annals of Canadian history and politics. But he probably does deserve some part of it.

It is also one of Stephen Harper’s undoubted achievements that he has created a new Conservative Party of Canada with its strongest base of support in the West (and especially in Alberta), where John A. Macdonald still has considerably less heroic stature than in his old hometown of Kingston, Ontario (midway between Toronto and Montreal). And it is interesting that Mr. Harper’s aggressively brief statement on Sir John A. Macdonald Day 2011 includes : “Sir John A. Macdonald was instrumental in laying the foundation of the Canada we know today, including the post-Confederation addition of three provinces, Manitoba (1870), British Columbia (1871) and Prince Edward Island (1873).”

4. “Canada has been taking shape for almost 500 years, and by New World standards is old”

There is another more profound reason that John A. Macdonald cannot qualify as Canada’s George Washington. And this has nothing at all to do with Stephen Harper. (Or so it seems right now, at any rate.)

The point here is somewhat subtle. But to try putting it in a nutshell, Canada is a different kind of country from the United States. The United States is a revolutionary country. Canada is an evolutionary country. (Some in the United States think this means that Canada is still not a “real country” at all. But no one who takes Canada seriously will agree with this. And I should also confess that I do take Canada seriously enough.)

The modern United States, that is to say, can be reasonably said to have begun with the first US national government of the late 18th century, of which Washington was the first president – and someone who handled both this and his earlier revolutionary military assignment so as to earn some high status as first among the equal American founding fathers.

Modern Canada, however, did not begin with the 1867 confederation of which Macdonald was the first prime minister, in the same kind of sense as the USA began with Washington. The creation of the 1867 confederation was just the next chapter in a longer story. As R. Cole Harris at the University of British Columbia wrote in his preface to the justly much admired late 1980s first volume of the Historical Atlas of Canada: “the volume has tended to confirm Harold Innis’s general insights … As Innis maintained, the pattern of Canada has been taking shape for almost 500 years, and by New World standards is old.”

To take just one case in point here, Macdonald is still well known, by some at least, for his “famous dictum ‘A British subject I was born, a British subject I shall die.’” Viewed from the perspective of the early 21st century, however, the old “British North America” is only one ingredient in Canada’s 500-year history that by New World standards is old.

In much of the country as we know it today the British empire was just a later addition to the multiracial (and multicultural) “French and Indian” fur trade. “Canada” itself is an aboriginal word. As the near-great Canadian economic historian Harold Innis also told us as long ago as 1930: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.” And the first people who called themselves “Canadians” were the French-speaking habitants of present-day Quebec.

Louis Riel has some significance in all this as well. He was a Métis – or a mixed-race person of both French and Indian (or aboriginal) descent.

Macdonald’s pre-confederation alliance with Cartier had given him some political sympathy and appeal for French-speaking Canadiens, concentrated in what became the province of Quebec in 1867. But Macdonald did not have similar feelings about the French-speaking and English-speaking mixed-race Métis (there were aboriginal and other as well as French and Indian combinations), who were in some respects the original pioneers of what became the Canadian West, after the new confederation’s purchase of the Hudson’s Bay Company lands in 1869.

Or so the hanging of Louis Riel in 1885 seemed to confirm. And, however you dot the “i”s and cross the “t”s, the northern new world that John A. Macdonald was most concerned to build was not the ancient multiracial and multicultural fur-trade frontier of the Canadian Métis.

It was instead the new frontier of the first self-governing dominion of the British empire, established by the confederation of 1867. A generation or so before, as an early 20th century British historian has written, the “second quarter of the nineteenth century” had been “the period in the settlement of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand which decided that those lands should be peopled mainly from Britain and should become parts of a free British Commonwealth of Nations.” And John A. Macdonald himself was a creation of this “period in the settlement of Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.”

Yet if you race very fast forward to the early 21st century, you can see plainly enough that still another new frontier has begun to evolve Рin many different if not all parts of Canada today. And through one of the more agreeable ironies of history, this new frontier looks increasingly more like the ancient multiracial and multicultural fur-trade frontier of the Canadian M̩tis, and increasingly less like the 19th century British North American settlement frontier, that created the John A. Macdonald who had been born in Glasgow, Scotland in 1815 and then moved with his family to Kingston, Upper Canada in 1820.

The United States also has an evolutionary history of this sort. And American society today is also much more diverse than the old Anglo-American frontier of the 19th century (which was almost as ethnically “English” – or WASP, as used to be said – as the new British North America that survived in the old French and Indian Canada after the American Revolutionary War).

But the governing political culture of the USA today was created in a dramatic revolutionary moment (or several such moments) in the late 18th century – and then reaffirmed in the American Civil War of 1861—1865 (in the wake of which, not exactly by accident, the confederation of 1867 quietly began the next chapter in the Canadian story).

The governing political culture of Canada today was not made from scratch in 1867. Even the narrowest anglophone political roots of the 1867 confederation stretch back in time. In some ways Lord Elgin’s actions as Governor General of British North America in 1848 are more important for Canadian democracy today than the creation of the 1867 confederation.

To sum up hastily, evolution is all Canada has. And Canada cannot have its own version of George Washington, because it has still not evolved into the kind of revolutionary country that the United States remains. (As apparently conservative as it may in other ways be. Or, as has been said, the United States may have somehow become a conservative country, but the values it conserves are still revolutionary. From a Canadian point of view, that is both its great glory and the source of so many of its troubles, which never seem to end.)

5. “John A. Macdonald and the Bottle”

It is also important to stress that John A. Macdonald’s inability to seriously qualify as Canada’s George Washington – for a number of very good and quite fundamental reasons – does not mean that he is altogether unworthy of continuing Canadian interest, both as the first prime minister of the 1867 confederation that we still live within today, and as a talented and intriguing historical figure in his own right.

My favourite among the various published birthday commemorations over the past week was an article by Tom Hawthorn, “a freelance newspaper and magazine writer who lives in Victoria, BC.” It appeared in the Globe and Mail, under the title “Raise a glass to Canada’s first prime minister.” If I were inclined to quibble, I would say the title should just read “the 1867 confederation’s first prime minister.” But in the spirit of Mr. Hawthorn’s piece, who cares about such details? (And of course what newspaper editor etc …)

Moreover, I wholeheartedly endorse Mr. Hawthorn’s last few sentences, where he urges us to concentrate on the near-great man’s “propensity to enjoy libations. So august a periodical as the Journal of Canadian Studies just four years ago published a footnoted article titled, ‘John A. Macdonald and the Bottle’ … Let other lands celebrate mighty warriors. We have clever dipsomaniacs.” (Where a dipsomaniac is, in case you’ve forgotten – I had to look it up myself:Â “a person affected with” a “morbid and insatiable craving, often paroxysmal, for alcohol” [Shorter Oxford English Dictionary – certainly what John A. would want us to use himself].)

The Journal of Canadian Studies article to which Tom Hawthorn referred was written by Ged Martin, Professor Emeritus at the University of Edinburgh – and a man who has “recently published a string of new research on Macdonald.” (It no doubt says something about something that the individual who may have done the most to advance the academic study of John A. Macdonald lately comes from a university in the Scotland of his birth, and not from Canada.)

At the start of his “John A. Macdonald and the Bottle” article Ged Martin aptly writes: “Two incarnations of John A. Macdonald survive in Canadian popular memory: the creative statesman of Confederation, and the politician who could not handle his drink. Impressionistic evidence suggests that, as many Canadians become vague about their history and cynical towards their politics, his achievements are forgotten while his weakness is emphasized … In popular history, the legend of an inebriated architect of Confederation has fed into the self-deprecating insecurity of national identity … Thus, the investigation of Macdonald’s relationship with alcohol represents something more than sensationalizing prurience, and contributes to a wider understanding of how Canadians have memorialized their history.”

Digging into the article somewhat more deeply, Martin explains that “Reports of Macdonald’s heavy drinking begin … in the mid-1850s.” (And some would say the death of his first wife in 1857 played some role.) From here his serious dipsomania lasted for more than two decades. But “he seems to have overcome his problem by 1877” – in its worst manifestations at any rate. By 1884 the sometime British colonial secretary, Lord Kimberley, was more definitely reporting: “I believe he has been more sober lately.”

That John A. Macdonald spent the last decade or so of his long political career comparatively sober is of course reassuring. But it remains the remarkable truth that he was drunk quite often during the period of his most creative statesmanship, and adroit and skilful leadership in the establishment of the 1867 confederation.

As Ged Martin goes on to explain, on the eve of confederation in late 1866 and early 1867, when the British North American leaders of the day went across the sea to the imperial metropolis in London, to put the finishing touches on their handiwork, the then colonial secretary, Lord Carnarvon, who certainly did not admire the dipsomania of the chief among these leaders, nonetheless “had to recognize that Macdonald, ‘in spite of his notorious vice,’ was ‘the ablest politician in Upper Canada,’ and to lose him ‘would absolutely destroy Confederation’ and pave the way for annexation” [to the United States that had just emerged from its own civil war].

Other similarly “censorious officials in London were soon ‘very greatly struck by [Macdonald’s] power of management and adroitness’” – even though shortly after he “returned from England” to Ottawa, for “a triumphant cabinet meeting on 5 May 1867,” the civil servant Edmund Meredith “recorded in his diary on 8 May that Macdonald was ‘carried out of the lunch room of the Executive Council office hopelessly drunk.’”

My own take on “John A. Macdonald and the Bottle” has always been that only a man of such habits could have put up with the vast human complexities of cobbling the 1867 confederation together, among so many conflicting cultural, economic, ethnic, geographic, linguistic, and religious interests, in the skilful way that there seems no doubt Macdonald did. The Canadian confederation has remained a fragile and difficult political construct to govern – as John A. Macdonald complained in his own lifetime. Some of his most successful successors as prime minister of Canada have also been somewhat strange individuals, in one sense or another – if never with quite the same dipsomaniacal passion. (Mackenzie King and Trudeau are examples that jump immediately to mind.)

As Tom Hawthorn from Victoria, BC implies, however, perhaps the greatest of Macdonald’s dipsomaniacal legacies are the engaging and enlivening drinking stories they have bequeathed to Canadian political history (which certainly needs the deeper human interest that such stories can bring). And it is a virtue of Ged Martin’s article of 2006 that it collects a number of the best-known stories of this sort.

There was, eg, the “January 1864 South Leeds by-election,” which “may be the source of a celebrated ‘John A. drunk’ story, in which Macdonald shocked an audience by vomiting on the platform but then won them over by claiming that his opponent’s policies had turned his stomach.”

And then “at the Quebec Conference in October 1864. Frances Monck, the governor general’s niece, recorded that Macdonald ‘is always drunk now, I am sorry to say.’ He had been found in his hotel room, with a rug thrown over his nightshirt, ‘practising Hamlet in a looking glass.’”

And then again, in the summer of 1866, “Macdonald and a cabinet colleague were seen ‘rolling helpless on the Ministerial benches’ [in the Canadian legislature of the day]. (The other inebriate was probably D’Arcy McGee: presumably the tale of Macdonald telling his colleague that the ministry could not carry two drunks, and that McGee must give it up, dates from this time.)”

And then once again, in the same year, in London, the decision to go ahead with Macdonald’s second marriage, to the Jamaican-born Agnes Bernard, “was probably taken around Christmas 1866, when Macdonald was deeply absorbed in the drafting of the new constitution.” At this same point, he “had also suffered extensive burns after setting fire to his hotel bed, an episode that he was anxious should not be reported.”

Finally, it should no doubt also be noted in all this that the mid to later 19th century was more tolerant of such bad behaviour in public than we are today (or even than the much later 19th century). As P.B. Waite has explained, in his overview of “Canada in 1874” : For “drinking no apology was expected or given in a Canada where consumption of alcoholic drink was four gallons per annum for every man, woman and child in the country … In 1873, of the twelve thousand arrests made in Montreal, fifty per cent were for drunkenness … In 1874 Toronto had a tavern for every 120 of its population” – which implies that “[c]hildren and abstainers aside, sixty people supported each tavern.”

6. Macdonald and the 21st century parliamentary democratic republic in Canada

There is one very final reason that John A. Macdonald cannot seriously qualify as Canada’s George Washington. And to me it is the most important of all.

The incarnation of Canada brought to legal life by the 1867 confederation was the first self-governing dominion of the British empire – something more than a mere British colony, but still something less than an independent nation in its own right. The constitution of the new Canada of 1867 was a mere Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom – and for many purposes could only be amended by the British Parliament, until the Constitution Act 1982 that Pierre Trudeau played such a large part in masterminding, in the wake of the failed Quebec sovereignty referendum of 1980.

Macdonald himself had wanted the new confederation to be known as the Kingdom of Canada, as a sign of its continuing attachment to the British monarchy – and what even George-Étienne Cartier applauded as “the monarchical principle” in government (which just seems a convenient shorthand for the residual elitism of various self-appointed Canadian establishments that in some respects endure even today). The British colonial office, however, demurred and the (in some ways still more colonial?) title of Dominion of Canada was finally adopted.

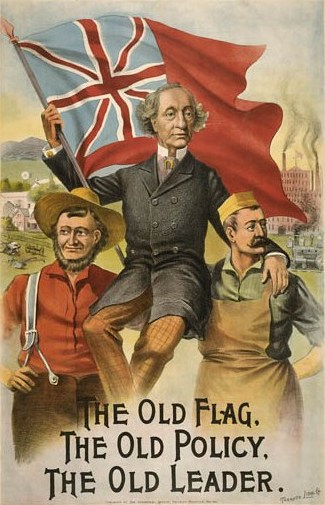

Similarly, it was in his last election of 1891 that John A. Macdonald actually declared “A British subject I was born, a British subject I shall die” – while his party’s election posters touted “The Old Flag, The Old Policy, The Old Leader.” The old flag was the British red ensign, not retired until the adoption of the present-day Canadian maple leaf flag in 1965. Technically, or legally and constitutionally, residents of Canada would remain nothing more than British subjects until the first Canadian Citizenship Act of 1947. (And they would be both Canadian citizens and British subjects until the Citizenship Act of 1977 made them just Canadian citizens.)

As recently as 2002, no less British-seeming a Canadian figure than the political humourist Larry Zolf was still writing that “Sir John A.’s famous dictum ‘A British subject I was born, a British subject I shall die,’ defined Canadianism for me for most of my life. In the summer of 1934 I was born a British subject in the city of Winnipeg … When the Queen Mum and King George VI made the first visit of a reigning British monarch to Canada, my father, a fervent monarchist … dressed me up in a Union Jack beanie, Union Jack socks, shorts and shoes, to stand and cheer the Royal couple.”

Yet by 2002, Mr. Zolf went on, “with my parents and Diefenbaker gone, the British subject in me was rapidly disappearing. The Queen Mum that I had loved was also being given a revisionist media grilling befitting an Imelda Marcos. The professional Kissinger-baiter, Christopher Hitchens, said the Queen Mum was a nazi sympathizer because she welcomed Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain back to England after the infamous Munich Pact in 1938.”

My own father, the son of British immigrants to Canada who – like others of his background – rebelled against his parents’ conviction that “Canada should become more like England” (in favour of the proposition that “Canada should become more Canadian”) left me with a different starting point than Larry Zolf (and then I am also more than 10 years younger). From the very beginning I have, as best as I can make out, inherited the view that we should politely walk away from the British monarchy, and become our own parliamentary democratic republic.

Which is to say that I do believe in our British heritage as one important strand in the Canadian past, present, and future. And I believe we should retain our British-style or “Westminster” parliamentary democracy, while substituting a made-in-Canada ceremonial head of state for the British monarch – on the model of India or Ireland say, and following a similar wave of the future in such places as Australia, Barbados, Jamaica, and New Zealand. Like the Mohawk poetess Pauline Johnson in an earlier era, I continue to believe that the “Yankee to the south of us must south of us remain.” But I don’t think that means we need to hang onto the last irrational vestige of our British colonial past forever.

John A. Macdonald, I am as certain as I am about anything in our complicated universe, would not agree with this point of view – and neither it seems would the Larry Zolf who concluded in 2002: “I may not be the British subject I was in 1939, but I still love the Queen Mum … And if it helps my country in any way, I’m ready, aye ready, to die a British subject.”

I am more impressed by the 2003 reflections of the University of Guelph professor emeritus of political science, Frederick Vaughan, in an intriguing book called The Canadian Federalist Experiment : From Defiant Monarchy to Reluctant Republic. As Professor Vaughan has explained: “The Constitution Act 1982 was the instrument that, with one stroke, severed Canadians from their ancestral monarchical foundations. With the [Canadian] Charter [of Rights and Freedoms, with which the Constitution Act 1982 begins], Canada began a new life as a nation, a republican nation. The Charter is based upon republican principles. It is the closest Canadians have ever come to a document that affirms the rights of the people.”

In the not too distant future, I believe as well, Canada will become a “free and democratic” republic in form and theory, as well as practice and substance – in the interests of its sheer survival. (And note that the phrase “free and democratic” already appears in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, in the Constitution Act 1982.) This will not finally turn us into a revolutionary country, like the great American republic next door. The new free and (parliamentary) democratic Canadian republic that looms before us will evolve from our long-term past (in fact this has already begun to happen), just like everything else.

One thing I am quite sure of even now, however, is that the John A. Macdonald who already seems implausible as the George-Washington-like founding father of the country we live in today – halfway between the old British monarchy of our colonial past and the new Canadian republic of our longest-term future – will seem even less plausible as a founder of our new republic when it finally arrives, in form and theory as well as practice. We have now reached a point in our evolution where we can see clearly enough that the real founders of Canada are not John A. Macdonald and George-Étienne Cartier and Charles Tupper and George Brown, or even Louis Riel, but the evolving Canadian people. And long may they (and/or we) continue to reign, in the 21st and many centuries beyond.

Great article.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Democracy Reform: Why John A. Macdonald can never be Canada’s George Washington (but a belated happy birthday anyway) : http://bit.ly/g0BuMz […]

http://topsy.com/www.counterweights.ca/2011/01/why-john-a-macdonald-can-never-be-canada%E2%80%99s-george-washington/?nohidden=1&sort_method=date

My thanks to Andrew Smith — for his comment, for the reference to Ged Martin’s research on John A. Macdonald in the article here, and for his own “Andrew Smith’s Blog : One Historian’s Perspective”, at http://andrewdsmith.wordpress.com/.

For those who don’t already know, Mr. Smith has taught history at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario, and is now at Coventry University in the UK. Anyone who has found my article here interesting enough to keep reading to this point will also be interested in his blog.