Middle Eastern pro-democracy uprisings ought to remind us of Canada’s Rebellions of 1837-38

May 24th, 2011 | By Ashok Charles | Category: Heritage Now

Libyans rally in Benghazi after hearing that Libyan rebels seized control of this strategic city on March 26, 2011, marking their first significant victory over Colonel Kadhafi's forces. UPI\Mohamad shukhi.

Considering that we admire and support the Middle Eastern rebels fighting to oust corrupt, undemocratic governments, it’s odd that we don’t give greater recognition to the Canadian popular uprisings which tried to achieve the same thing.

In the 1830s the governments of Upper and Lower Canada – what are now Ontario and Quebec, respectively – were in the hands of appointed officials rather than elected representatives; the Legislative and Executive Councils were dominated by oligarchies composed largely of Tory businessmen, politicians and clergy. In Upper Canada the ruling elite was known as the Family Compact and, in Lower Canada, as the Château Clique. Their virtual control of government ensured that legislation served their interests.

As oligarchic regimes tend to do, the Family Compact and the Château Clique used force, intimidation and violence to maintain control. John Ralston Saul observes that “The Château Clique got away with acting as a rogue government, arresting people at random, frightening people and bankrupting them by locking them up.” In their bid to dominate the troublesome elected Assemblies both syndicates were known to send thugs to public voting platforms to prevent reformers from casting ballots.

The ruling elite also clamped down hard on the pro-reform press. In Toronto, the office and printing equipment of William Lyon Mackenzie’s newspaper, the Colonial Advocate, were vandalized by regime loyalists and, in Montreal, journalists and editors were jailed for criticizing the unelected Legislative Council, controlled by the Clique.

C.W. Jefferys’ famous enough sketch of the December 5 march down Yonge Street in the Upper Canadian Rebellion of 1837. Not for the last time angry people would try to attack the provincial capital in Toronto.

When a list of grievances, demanding that public spending be placed in the hands of elected representatives and that corruption be eliminated from government, was formally presented to the imperial government by the Assembly of Lower Canada the regime responded harshly; it dismissed every recommendation and then further curtailed the meager powers held by the Assembly.

This blatant disregard for the people’s voice, as expressed by elected representatives, convinced many reformers that change via the legislative route was impossible. Political organizations were formed which contemplated other options. For example, at an “anti-coercion meeting” in what is now Vaughan, Ontario, the following resolution was passed: “That Government is founded on the authority, and is instituted for the benefit of, a people or community, and not for the benefit, honour, or profit of any man, or any class of men, who are only part of that community; that the doctrine of non-resistance to arbitrary power is slavish, absurd and discreditable…”

* * * *

Painting of the Assembly of the Six Counties by Charles Alexander Smith. The Assembly of the Six Counties / Assemblée des six-comtés was a gathering of “Patriotes” held in Saint-Charles, Lower Canada on October 23 and October 24, 1837, despite a June 15 Proclamation of the government forbidding public assemblies. It was the most famous of various public assemblies that became a prelude to the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837—38.

The BBC ‘s recent observation that, in Tunisia, the “unrest is …seen as drawing on deep frustration with the ruling elite and the suppression of political freedoms,” could just as accurately have described Canada in 1837.

In the months leading up to the Lower Canada Rebellion there were several protest rallies in Quebec. Unlike the mass demonstrations which occurred earlier this year in Tunisia and Egypt, however, the Canadian protests were unsuccessful in winning concessions from the ruling regime. As in Libya, the decision was made to attempt regime-change by force.

Demonstrators on an army tank in Tahrir square during protests in Cairo 29 January 2011. Photograph: Yannis Behrakis, Reuters.

Indeed, the features shared by the uprisings which occurred here and the ones currently in play in the Middle East and North Africa are intriguing.

In both cases widespread discontent with exploitative, undemocratic rule and blocked access to legislative change led to attempts to overthrow and replace the standing government. The insurrections drew participants from every social strata and include farmers, tradespeople, journalists, professionals (a surprising number of doctors played key roles in the Canadian rebellions), and politicians. Entire towns and districts came under rebel control. Impassioned, poorly-equipped, untrained insurgents faced authoritarian regimes fielding professional armies, which were supported by loyalist militias.

Charles Beauclerk’s painting of the dispersal of the insurgents at la bataille de Saint-Eustache, le 14 décembre 1837, Lower Canada.

At a severe disadvantage in regards to numbers and resources, our rebels won a battle or two but they were no match for the combined strength of the British army and local militias loyal to the ruling regime. In the absence of the kind of sympathetic international support the Libyan rebels are benefiting from, the Rebellions were quashed – swiftly in Upper Canada and after a more prolonged engagement in Lower Canada.

Of course, only the United States could have intervened effectively and, although ideologically aligned with the democratic reform sought by the Canadian rebels, they were disinclined to renew hostilities with the British after the bloody war they had waged to win independence (and the still more recent War of 1812—14). It must also be acknowledged that American intervention would likely have meant the annexation of Canada rather than its “liberation.”

Egyptian protesters shout slogans demanding faster reforms during a demonstration at Cairo's Tahrir Square on April 8, 2011 in Cairo, Egypt. Tens of thousands of Egyptians gathered two months after president Hosni Mubarak was ousted. UPI.

Many of the rebels who evaded capture, including Mackenzie and several other leaders, did find refuge in the neighbouring United States. From there, with the support and involvement of Americans sympathetic to the Canadian struggle, who acted without state sanction, a series of raids were attempted, seeking to gain control of Canadian territory close to the US border.

The British army, augmented by loyalist militias, successfully fought off these efforts by the rebels and American sympathizers to gain a permanent foothold in Canada. The failure of the Rebellions was then complete. The regime had held.

* * * *

In November 1838 Nils von Schoultz led 200 Canadian exiles and US “Hunter Patriot” sympathizers in an attack against Prescott, Upper Canada – in the four-day Battle of the Windmill against British regulars and the local Canadian militia. This was one of several such raids that year on Upper Canadian border towns from US centres.

As order was being restored, the governments of Canada (like that of Iran more recently) used a show of brutal retribution to discourage further dissent. Civil rights were suspended. Militias and gangs of loyalist thugs were unrestrained from exacting revenge on Rebellion supporters and suspected supporters. Looting, beatings, and the razing of homes were widespread. There were incidents of gang-rape and outright murder. As one history book puts it, “There can be no doubt…that the government and military command intended to terrorize the population into submission.”

Capital punishment was meted out to more than two dozen of the captured rebels and raiders – including American sympathizers who had been involved in the border skirmishes. Over one hundred men were exiled to hard labour in Tasmania, Australia, and dozens more were kept in prison. Those who were deemed least culpable were pardoned upon pledging renewed allegiance to the Queen and her colonial government.

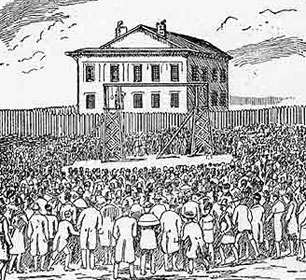

The two Upper Canadian rebels to face the gallows, Samuel Lount and Peter Mathews, neither of whom had killed during the conflict, were publically hanged in downtown Toronto. Lount’s family was not allowed to see him for the first two months of his three-month imprisonment and after his execution they were denied his body. The state confiscated his property, leaving his wife and seven children destitute.

The two Upper Canadian rebels to face the gallows, Samuel Lount and Peter Mathews, neither of whom had killed during the conflict, were publically hanged in downtown Toronto. Lount’s family was not allowed to see him for the first two months of his three-month imprisonment and after his execution they were denied his body. The state confiscated his property, leaving his wife and seven children destitute.

In the years immediately after the Rebellions, thousands of Canadians, traumatized by the brutal retaliation in which the authorities were complicit (and worse), and disheartened by the failure to achieve a government that was responsible to the citizenry, crossed the border to the democratic south.

Public hanging of Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews at northeast corner of King and Toronto Streets in the City of Toronto, Upper Canada, April 12, 1838.

Though the Canadian rebels were defeated, their forceful bid for more democratic government had a lasting impact. The bold grassroots uprisings demonstrated that the people of Canada would not tolerate oppressive, unrepresentative government and hastened the quieter more progressive political evolution which followed, in the 1840s.

Canadians, rightfully, acknowledge the legitimacy and the courage of those who are risking their lives to advocate for democratic reform in the Middle East. Those who fought for the rights we enjoy, by rising up against exploitative, undemocratic government, deserve no less.

Ashok Charles is a Toronto-based photographer, a graduate of Ryerson Polytechnical University, and chair of the Toronto chapter of Citizens for a Canadian Republic.

Grass roots efforts are so important, ag note the stop harper sign shown by a young page during the throne speech! Being Brave taking a risk!

I totally agree… our ancestors died for our freedom… we can’t just let them take that away without a sound… free speech is now gone… What are we doing Canada?