Now that John Ibbitson’s next Canada is here at last, where is it going to take us?

May 22nd, 2011 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In Brief

Vancouver Canucks fan lifts up her jersey to confuse San Jose Shark Ben Eager, in Game 2 of the NHL Western Conference final. Here’s hoping one thing the next Canada means is that a Canadian team will win the Stanley Cup in 2011! Photograph by: Rich Lam, Getty Images.

On this May 24 holiday weekend there can be no doubt that the early 21st century has launched some kind of new Canada. Or, more aptly perhaps, in the wake of the May 2, 2011 Canadian federal election the “next Canada” that John Ibbitson was saying “will not be denied forever,” in the wake of the Canadian federal election of June 28, 2004, has arrived with a vengeance at last.

Back when our rather angular (if that’s the right word?) counterweights site first started, in late August 2004, Dr. Randall White was arguing that “Ibbitson’s own descent from the rural hinterland – which is in some ways more exurban or even vaguely suburban nowadays than ‘rural’ used to be – has given him an intimate grasp of current conservatism in Ontario and Western Canada.”

Somewhat less than seven years later, in the recent august pages of the Globe and Mail, no less an authority than Preston Manning has reported that: “From the very beginnings of Confederation, the Laurentian region, Quebec and Ontario together, has dominated federal politics. But on May 2, that political centre of gravity shifted westward, the new and dominant alliance becoming that of Ontario and the West together.”

There is a problem with this new alliance, as even Mr. Manning recognizes. The old Liberal coalition founded by Wilfrid Laurier and William Lyon Mackenzie King did not become “the natural governing party of Canada” in the 20th century because it put together some “Laurentian” regional combination that could typically win a majority of seats in the federal parliament. (In the elections of 1921, 1925, 1926, 1930, 1945, 1957, and 1958, eg, the Conservatives won more seats in Ontario than the Liberals – by substantial margins.)

The Liberals were “the natural governing party of Canada” in the 20th century because they customarily brought the French-speaking majority in Quebec into the English-speaking mainstream of Canadian federal politics. And whatever else, Preston Manning’s “new and dominant alliance … of Ontario and the West together” lacks this kind of “natural governing party” distinction.

Mr. Manning himself tells us that: “What should be increasingly apparent is that if new and stronger bridges are to be built between Quebec and the rest of Canada, they will have to be primarily constructed not by federal politicians on constitutional grounds, but by private-sector decision makers and provincial leaders on the grounds of economic and interprovincial relations … National unity will thus depend increasingly on such measures as increased Quebec-Ontario trade and increased co-operation between the energy sectors of Quebec and the West, and on greater interprovincial co-operation, as discussed recently in a Montreal Economic Institute report calling for a new Quebec-Alberta dialogue.”

1. Pat Murphy on (Pierre) Trudeau and PM Harper

Something of a similar spirit haunts a recent column by the Troy Media contributor Pat Murphy, rather misleadingly entitled “Believe it or not: Harper’s more popular than Trudeau ever was.”

Pat Murphy, a history and economics graduate from University College Dublin, Ireland, who has contributed articles to Troy Media, the National Post, History Ireland, Irish Connections Canada, Templar History and Breifne.

Mr. Murphy does point to one poignant (and, no doubt, significant enough) recent Canadian electoral statistic. Over the past four federal elections Stephen Harper’s new Conservative Party of Canada has quite dramatically, and impressively, increased its share of the popular vote in the so-called “Rest of Canada” outside la belle province du Québec – from (in round numbers) 37% in 2004, to 40% in 2006, 43% in 2008, and 48% in 2011!

Mr. Murphy, however, is still more concerned to stress a related statistic that is almost certainly less impressive (and significant) than he imagines – or at least pretends. In 2011 Stephen Harper’s Conservatives won (to be quite exact) 47.65% of the popular vote in the Rest of Canada outside Quebec, compared to a mere 42.35% of the same statistic for Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal Party of Canada “at the height of Trudeaumania” in 1968.

Mr. Murphy recognizes: “Of course, it can be argued that excluding Quebec from a review of voting trends is itself an artificial construct. After all, Quebec is a part of Canada.” But, he goes on, “Quebec is also quite different from everyone else, a difference that embraces history, language and culture. And further, it’s a difference that everyone acknowledges and Quebec proudly proclaims.” So, he urges: “if it’s legitimate to consider the political identity and aspirations of Quebec, then it’s equally valid to focus on the identity and aspirations of the ROC. And to do that, to fully understand what’s happening politically, it’s necessary to separate the Quebec vote from that of the ROC.”

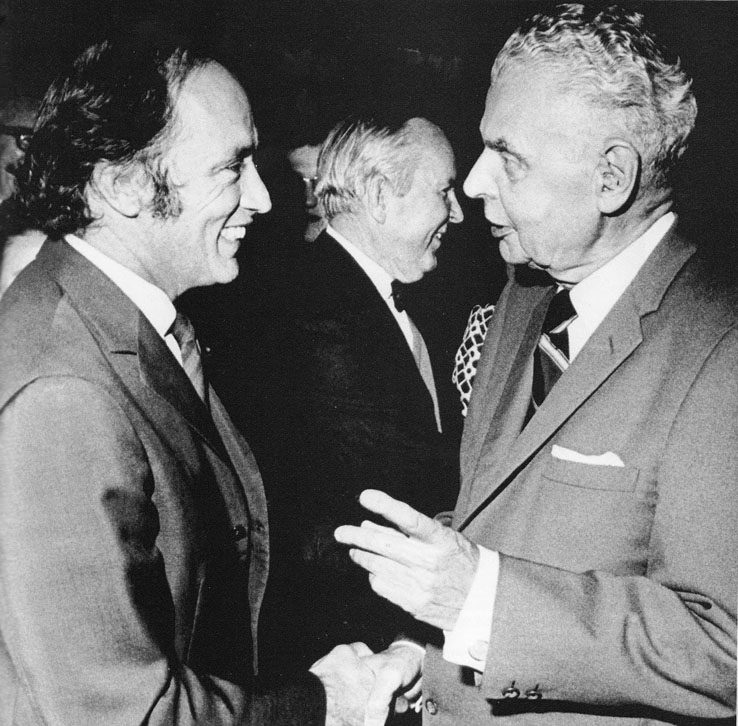

Pierre Trudeau and John Diefenbaker (who admired Trudeau, not because he was popular, but because he was someone from Quebec who believed in “one Canada” and would stand up against Rene Levesque).

Deconstructing all the political half-truths and dubious assumptions in this kind of argument (which does, we would again submit, bear some serious similarity to Preston Manning’s view of “What should be increasingly apparent … if new and stronger bridges are to be built between Quebec and the rest of Canada”) could take up most of the pages in a paperback book. But a critical comment writer on Pat Murphy’s original Troy Media posting can at least get us started on a much shorter journey to one essential crux of the new “next Canada” dilemma.

So “smacdon2011” has (only a little impolitely?) complained that Mr. Murphy’s “Believe it or not: Harper’s more popular than Trudeau ever was” is “a bogus article. First of all, it is based on the idea that Trudeau should even be a measuring stick for ‘popularity.’ I don’t see the point. As far as I know Mulroney was the most popular prime minister in the history of Canada. And we know where that got him.”

2. Stephen Harper in 2011 and Robert Borden in 1917

In fact, Mulroney was not quite “the most popular prime minister in the history of Canada,” as Pat Murphy judges such things. The Mulroney Conservatives did, in the federal election of 1984, win an actual bare majority of the popular vote (50.0%) – and not just in the rest of Canada outside Quebec, but in all of the country, anglophone and francophone, from coast to coast to coast. But similar cross-Canada bare majority feats had been performed by the St. Laurent Liberals in 1953 and 1949. And, without going back into the more ancient history of the confederation, the Diefenbaker Conservatives won 53.7% of the cross-Canada popular vote in 1958, and the Mackenzie King Liberals won 54.9% in the wartime election of 1940.

Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, whose Liberal government won almost 55% of the cross-Canada popular vote in 1940, chats with actress Shirley Temple during her visit to Ottawa in 1944.

Perhaps still more to the point, the greatest share of the popular vote won by any party or political alignment in the entire history of the Canadian confederation since 1867 is still the 57.0% of the cross-Canada turnout taken by Robert Borden’s Conservative-Unionist government in the wartime election of 1917. There are various fascinating aspects of this government and this era in Canadian political history – several of which do seem to have poignant echoes for us today. But to focus on just the key point for our concerns here the Borden Conservative-Unionist government that won such an apparently commanding victory in 1917 had a largely “Rest of Canada” base of support, not unlike the Harper Conservative government that has at last won a majority of seats in the Canadian House of Commons in 2011.

There were 235 seats in the Canadian House in 1917. A bare majority would have been 118. Robert Borden’s Conservative-Unionist forces took a grand total of 153 – including 74 of 82 seats in Ontario, 14 of 15 in Manitoba, 16 of 16 in Saskatchewan, 11 of 12 in Alberta, 13 of 13 in BC, and only 3 of 65 seats in Quebec.

Robert Borden from Nova Scotia, whose Conservative-Unionist government won a still record 57% of the cross-Canada popular vote in 1917, playing golf in his later years.

In the end, however, this coalition (and it was a coalition of sorts : between Conservatives and, so to speak, more conservative-minded Liberals – the only combination that PM Harper seems interested in today, some 94 years later) would not last. The real transformational election for the subsequent history of the confederation came in 1921, not 1917, when Mackenzie King and the Progressives (“Liberals in a hurry,” as he put it) began to resurrect the old Laurier Liberals who would (eventually, after a few further bumps in the road) go on to become what later pundits would celebrate (or bemoan) as “the natural governing party of Canada.” And, again, the ultimate trump card here was that Mackenzie King – and his textbook Quebec lieutenant, Ernest Lapointe –Â could almost always count on the French-speaking majority in Quebec.

3. The Liberal-NDP majority that underpinned the Trudeau era

So … to try to draw an already too-long story to a quick enough conclusion, “smacdon2011” does seem to us quite right when he complains about the mis-readings of history which lie in “the idea that Trudeau should even be a measuring stick for ‘popularity.’”

NDP leader Tommy Douglas in 1965: though not in government he played an important in Lester Pearson’s creration of the modern Canadian service state, 1963—1968.

Pierre Trudeau, we would argue at any rate, remains the great colossus of recent (and even not so recent) Canadian political history not because he was unusually popular in Pat Murphy’s sense, especially in the Rest of Canada outside Quebec, but even in Canada from coast to coast to coast. He is important because of what he contributed to the Canadian future. (And this, we would agree as well, is not without its weaknesses and ambiguities, but it does remain unique. Here again we point to another tentative assessment of Dr. Randall White, on the 10th anniversary of Trudeau’s death last September: “Whether you loved or loathed him, no one is as big as Pierre Trudeau in Canadian politics today.”)

At the same time, there is also something about the popular support for Trudeau’s governing regimes that Pat Murphy’s over-simplistic perception of the role of individual leaders obscures. Pierre Trudeau was just as arrogant as Stephen Harper, no doubt. He was certainly as contemptuous of the media. And there probably is something to the argument that the increasingly excessive growth of prime ministerial power which Mr. Harper has taken to new extremes has certain earlier precedents in the era of Pierre Trudeau, from 1968 to 1984.

Yet Trudeau’s broad social and economic policy, so to speak, drew on a broader base of popular support than his own party’s numbers suggest – in a way that cannot at all be said for Mr. Harper today.

In an earlier incarnation Pierre Trudeau actually belonged to the federal New Democratic Party. He began as Liberal prime minister in 1968 as a legatee of Lester Pearson’s crystallization of the modern Canadian service state over the preceding five years. This owed a lot as well to the New Democratic Party under the former Saskatchewan premier Tommy Douglas. From 1972 to 1974 Trudeau governed as a minority prime minister with the informal but quite essential support of the David Lewis NDP in the Canadian House of Commons.

In this same context, in all of the five Canadian federal elections Pierre Trudeau’s contested as prime minister, from the later 1960s to the early 1980s, the combined popular vote of the Liberals and New Democrats together – and not just in the “Rest of Canada” outside Quebec, but across Canada, from coast to coast to coast – was always well into majority territory: in round numbers, 62% in 1968, 56% in 1972, 59% in 1974, 58% in 1979, and 64% in 1980.

4. Now the West is in … and Quebec has at least started to come back

There is much grist for several different kinds of mills in all these numbers, it seems to us. And if there is little doubt that Stephen Harper is going to have his own way on many different (and no doubt often quite strategic) issues over the next four years – including Supreme Court appointments, and ending at least the kinds of public subsidies for political parties he doesn’t like – it also remains not at all clear just where Preston Manning’s “new and dominant alliance … of Ontario and the West together” is going to take the Canadian confederation that will celebrate its 150th birthday on July 1, 2017.

As the 1917 election shows, this kind of alliance is not in fact altogether without precedent in the Canadian past. What this past suggests is that “Ontario and the West together” is not in fact a stable formula for governing any Canada that includes the French-speaking majority province of Quebec. What the last two generations of Canadian political history have finally shown is that there can be no Canada that does not include Quebec. And the most compelling recent statistics here may well prove to be the Conservative share of the popular vote in Quebec : 2004 — 9%, 2006 — 25%, 2008 — 22%, and 2011 — 17%.

Preston Manning will neither like nor assent to this kind of analysis. His view is that “here is the great danger for the NDP [the possessor of the lion’s share of the Quebec vote at the moment, of course, in what could yet ultimately prove the most profoundly significant as well as altogether surprising result of the May 2, 2011 contest]: In the past, both of the major federal parties, the Liberals and the old Progressive Conservatives, bent over backward to accommodate Quebec’s demands. In doing so, they increasingly alienated major segments of the electorate in the rest of the country. In the end, their Quebec supporters turned against them. It happened to Pierre Trudeau, it happened to Brian Mulroney and it could happen to Jack Layton even more quickly and dramatically.”

Mmmm … well … as they have long said along the banks of the Ottawa River, “maybe, maybe not.” Our own guess is that certain long-term fundamentals of Canadian political history have not actually changed all that much. Quebec may have still not yet found the old federalist instincts it lost some time ago. But there seems increasingly little doubt that the old “separatist” instincts of the past several decades actually have started to wane, among the Canadian people of Quebec if not quite their rulers of the moment.

Quebec NDP MP-elect Ruth Ellen Brosseau visits her riding with Jack Layton’s Quebec lieutenant, Thomas Mulcair. Who knows where the surprising 2011 federal New Democrat triumph in Canada’s French-speaking majority province will finally lead?

Or, if you like, the West is in with a vengeance at last, and that’s now old news. The new news is that Quebec is back – or at least has started to come back. And as in the past the future of Canadian federal politics will finally lie with whatever among the current contending forces can figure out how to bring the French-speaking majority in Quebec back into the Ottawa mainstream, more or less, without terminally upsetting the “Rest of Canada.”

If what Warren Kinsella likes to call the “Reformatories” from out West really do want to found some new Conservative natural governing party of Canada for the 21st century, they should stop worrying so much about all the Mike Harris residues in Ontario, and start trying to re-engage the Quebec voters they began to win over in 2006, and have now progressively faltered among in both 2008 and 2011. Quebec could very well once again be they key to what happens across Canada, coast to coast to coast, four years from now, in 2015. (And, believe it or not, there are many of us, in various parts of the Rest of Canada, who don’t really object to this at all! The country works best, for the great majority everywhere, when Quebec plays at least some prominent role in guiding it.)