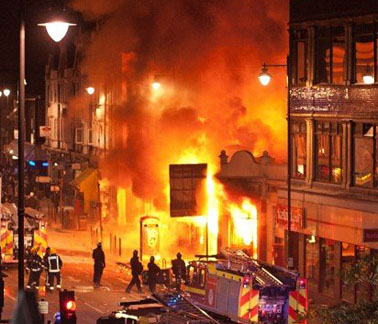

What would Orwell think about the UK riots in the summer of 2011?

Aug 11th, 2011 | By Randall White | Category: In BriefAugust, according to the English poet W.H. Auden in 1935, was supposed to be “for the people and their favourite islands.” Apparently times have changed. In the strange summer of 2011, August is for “UK riots: Sharing of police between cities ‘reviewed hourly’ … Theresa May orders police chiefs to cancel all police leave as forces are stretched across the UK” ; and “England riots: Are brooms the symbol of the resistance?”

Still more to the point, maybe: “Riots shake faith in UK austerity, stability… In the eyes of the financial markets, Britain was supposed to be a model of successful, sustainable austerity and a safe haven in which the world’s rich could buy houses and stash their savings … The riots that turned London and some other English cities upside down this week have undermined that model, raising questions about the sustainability of spending cuts and a widening gap between rich and poor.”

There are, of course, of course, those who still bridle at this last point of view. A few days ago the Globe and Mail in Toronto (said to be “the citadel of British sentiment in America,” back in 1933) was reporting that: “Efforts by some opposition politicians to link these events to Prime Minister David Cameron’s spending cuts have been met with incredulity in the affected neighbourhoods, where those cuts have not yet had any municipal effect.”

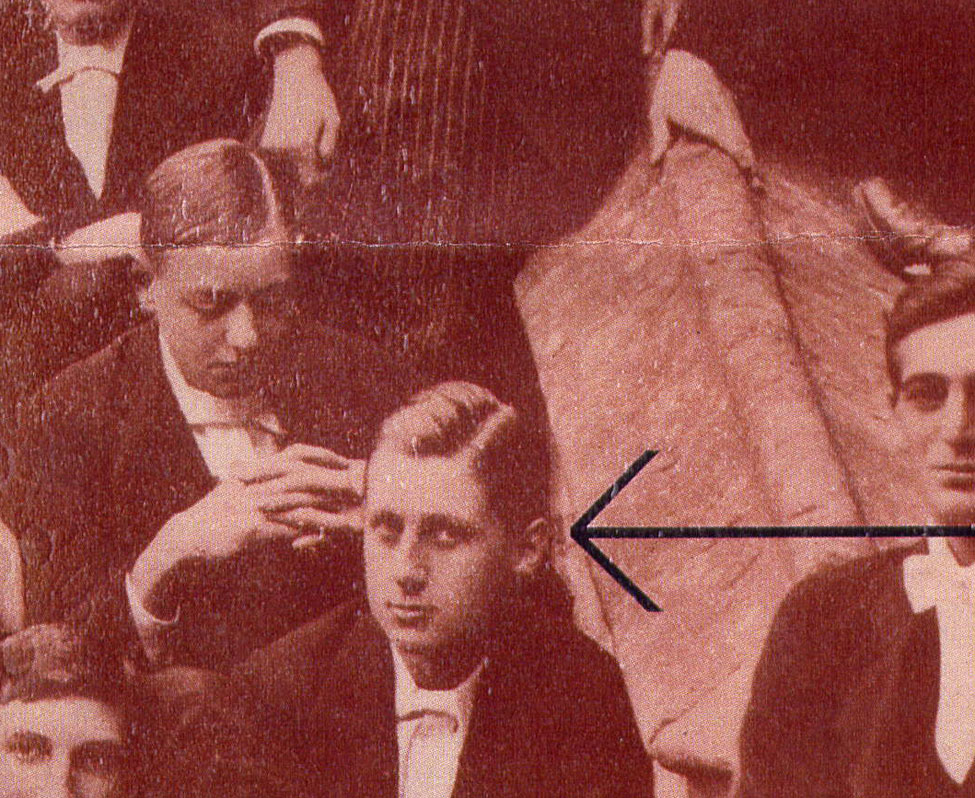

Eric Blair at Eton, ca 1919, before he joined the Imperial Police in Burma, and then went Down and Out in Paris and London, to become George Orwell.

Yet if a specific, direct “municipal” link between the riots and the cuts is premature, something about the background in which the quite aggressive UK cuts policy has arisen remains provocative. Yesterday the Globe and Mail published a piece by Mel Cappe, a professor of public policy at the University of Toronto and a former Canadian high commissioner to the United Kingdom. It was headlined “Britain’s unentitled riot at the loss of their future.” And, among various related things, Professor Cappe observed: “When I lived in London, Brits were surprised that I found British society so hierarchical and stratified. Most of the elite felt they had come a long way in becoming a postmodern, egalitarian society. A Canadian, proud of our multicultural and mixed ethnic society, found that the Brits still had a long way to go.”

* * * *

Like others, no doubt, I have heard similar things from other Canadians who have lived and worked in London for a time, even in the 21st century (as altogether agreeable a place as everyone who has ever been there, even briefly, also knows it otherwise is). And this has finally made me wonder what the great saint of English political writing in the first half of the 20th century would make of the UK riots in the summer of 2011 – if he were still alive today?

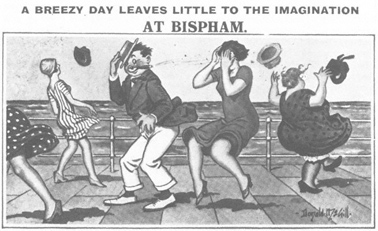

A Donald McGill postcard : part of the traditional culture of the English working class that Orwell liked – and admired. (Bispham is an old English seacoast resort, on the Irish Sea, just north of Blackpool and northwest of Manchester.)

There is an all too obvious sense in which endlessly wondering what George Orwell (1903—1950) would have thought of this, that, and the other thing which has happened long after his death is a foolish exercise. It can still sometimes have its uses nonetheless. And what strikes me almost right away in this case is Orwell’s highbrow-populist celebration of traditional English working class culture (as in, eg, his “dirty postcard”essay of 1941 on “The Art of Donald McGill”).

More than a few critics have made fun of George Orwell’s efforts at “going native in his own country” – trying to find a place for himself in the indigenous working-class culture he came to admire quite profoundly. To start with he was, he famously confessed in 1937, “born into what you might describe as the lower-upper-middle class” – as Eric Blair, the son of Richard Blair, an official of the opium department of the British Raj in India. Through his own academic talents and the promotional zeal of his mother (the former Ida Limouzin, daughter of a French merchant in Moulmein, Burma), Eric Blair wound up going to Eton College – a leading training ground for the old English ruling class. Following in his father’s footsteps, as it were, on graduating from Eton he joined the Imperial Police in Burma.

George Orwell mid 1940s, in the workshop corner of his Islington flat, north London (though some have said the bookshelves he made fell apart!).

Eric Blair left England for Burma late in October 1922. In that field over the next several years he discovered he did not believe in the British empire – or in any version of the “upper-middle class, which had its heyday in the eighties and nineties [1880s and 1890s, that is], with Kipling as its poet laureate,” and then became “a sort of mound of wreckage left behind when the tide of Victorian prosperity receded.” He resigned from the Imperial Police in 1928. Over the next 17 years he transformed himself into the George Orwell (a pen name he adopted in 1933) who at last became a famous English working-class “democratic Socialist”political writer, with the publication of Animal Farm in 1945. Shortly after, in his best working-class-culture mood, he described the “ten qualities that the perfect pub should have” in an article called “The Moon Under Water,” published in the Evening Standard, 9 February 1946.

It seems clear enough that a few things about the lower-upper-middle class Eric Blair who went to Eton never quite left the mature George Orwell. Yet as his biographer Bernard Crick has explained, the mature Orwell that Eric Blair finally perfected was “an English Socialist of the classic kind … left-wing, but also libertarian, egalitarian and hostile to the Communist Party.” Despite his own birth in India, his French mother, and his time in Burma, Orwell was also “quintessentially English.” But his “Englishness was not … that of the upper classes; it belonged to the radical tradition of Cobbett, Blake, Bunyan and the Levellers.” Orwell believed passionately in the future of a quite traditional England – or even Britain or the United Kingdom. But he also seems to have understood that for this kind of future to work in the new world of the 20th century and beyond, it would have to give a much more honoured place to the traditional culture of the English working class. As the Scottish novelist Andrew O’Hagan has urged much more recently, “Orwell’s view of his England relied on a notion of the innate self-respect of the English working class.” (And this helps explain the rather odd working-class intellectual persona Orwell finally perfected for himself during the last decade or so of his all-too-short life – all the way down to his hybrid style of dress and alleged wood-working hobby.)

You can see something of the initial success of Orwell’s working-class culture advocacy in such British movies of an earlier era as Look Back in Anger (1959, starring Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, and Mary Ure, and directed by Tony Richardson) or Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960, starring Albert Finney, Shirley Anne Field, and Rachel Roberts, and directed by Karel Reisz). By the 1980s, however, England or Britain or the United Kingdom had begun to turn its back on all this. A few decades later Andrew O’Hagan himself, in a lecture republished as an early January 2009 article in the Guardian, was lamenting a new “age of indifference … The English working class is dead – its traditions and values have been replaced by sentimentality and the false promises of celebrity and credit cards.” O’Hagan went on: “How did this vast and overwhelming numbness of England’s working class come about? Thatcher is said to have been genuinely shocked by the ease with which England rolled over when she entered with her rapier drawn. Most people were willing to see their society lose its unions and its nationalised industries – even its status as a society – without a blink … By the late 1990s, the working class were no longer a working class – their traditions, habits, jobs, even in some places their speech, were given over to new forms of transcendence offered by celebrity culture and credit cards and the bogus life of the fantasy rich. Woolworth’s was on its way to closing down for ever, as finally it did this week. Depression among the children of the poor, many of them third-generation unemployed, was recorded the other day as being the worst in Europe.”

You would never know it by listening to UK Prime Minister David Cameron lately, but this kind of recent political and cultural analysis has not been confined to the English left. In his 2009 article, Andrew O’Hagan went on again: “In Mind the Gap (2004), Ferdinand Mount provided a surprising account of the situation of the English working class, coming as it did from the centre right. He wrote that the so-called underclass seem ‘to me impoverished not simply in relation to the better-off in Britain today but in relation to their own parents and grandparents. And the upper class are uncomfortably aware of it, which is why they show so little respect and affection for the lower classes.’ He attacks the notion that England has been progressively (or assertively, as John Major had it) becoming a more classless society. The English working class is, he wrote, ‘uniquely disinherited, and the most important ways in which it is disinherited are the more crippling because they are largely hidden from us’.”

Something in all this seems to me to match Mel Cappe’s observations from Toronto yesterday, about how British society remains “so hierarchical and stratified,” and how, ever so sadly (and absolutely appallingly to those of us who still think we do have a future, no doubt at all) “Britain’s unentitled riot at the loss of their future.”

Orwell the mature writer at work – in what he seems to have thought of as the working-class outfit he invented for himself!

Andrew O’Hagan’s Guardian article from early 2009 also seems to me to end on a suitably relevant Orwellian note (though pardon one slight repetition of a phrase that could probably stand to be repeated several more times again) : “The English working class – including their new ethnic groups, out of Asia, Africa and eastern Europe – are less conscious of themselves as a political class than at any time since the mid-19th century … Orwell’s view of his England relied on a notion of the innate self-respect of the English working class … Perhaps he would have been disbelieving to see how the English poor have themselves become conjoined to their own adversity, distanced from their own collective powers and distracted from their best traditions of non-acceptance, dreaming of goods and fame as being great and lasting values. Or maybe he always knew it and wondered why no one was saying it. At the close of Homage to Catalonia [Orwell’s book on the Spanish Civil War, first published in 1938], as he arrives back in England, we find this … ‘And then England – southern England, probably the sleekest landscape in the world. It is difficult when you pass that way, especially when you are peacefully recovering from sea-sickness with the plush cushions of a boat-train carriage under your bum, to believe that anything is really happening anywhere’.”

And then O’Hagan himself ends with: “Nothing much has been happening since [some 71 years later, as O’Hagan wrote], except the quiet, invisible business of the people being walked over, and saying nothing, and thinking that’s just the way it is.”