Constitution Act, 1982 “severed Canadians from ancestral monarchical foundations” (no wonder PM Harper doesn’t like it!)

Apr 17th, 2012 | By Citizen X | Category: In Brief “And Barbara it’s starting to rain, very gently.” So a youthful Peter Mansbridge told David Frum’s mother – and TV viewers across Canada – as Elizabeth II approached the table to sign the proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982, 30 years ago, on Saturday, April 17, 1982.

“And Barbara it’s starting to rain, very gently.” So a youthful Peter Mansbridge told David Frum’s mother – and TV viewers across Canada – as Elizabeth II approached the table to sign the proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982, 30 years ago, on Saturday, April 17, 1982.

The ceremony was held outdoors on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. After the signing of the proclamation the gentle rain grew stronger. When the Queen began some concluding remarks (sheltered under a covered dais), the watching crowd on the Hill was covered by umbrellas. The Constitution of Canada was being “patriated” from the Parliament of the United Kingdom at last. It may have been appropriate that this was happening in a respectful local burst of the weather for which the old imperial metropolis was famous.

The original main part of Canada’s so-called written constitution was the British North America Act, passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1867, and given royal assent by Queen Victoria. For many years it could only be amended by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. For matters dealing with both federal and provincial governments this remained the case until the Constitution Act, 1982 – which at last provided a complete method of constitutional amendment inside Canada , and thus “patriated” the Constitution from the United Kingdom.

The original main part of Canada’s so-called written constitution was the British North America Act, passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1867, and given royal assent by Queen Victoria. For many years it could only be amended by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. For matters dealing with both federal and provincial governments this remained the case until the Constitution Act, 1982 – which at last provided a complete method of constitutional amendment inside Canada , and thus “patriated” the Constitution from the United Kingdom.

There are two main ingredients in the Constitution Act, 1982. The first is a Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which “guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” The second is a complex or at least demanding “procedure for amending Constitution of Canada.”

There are some who say that, except for matters dealing with the federal government alone, this procedure has proved so demanding as to make the present Constitution of Canada engraved in stone. But the Charter has won great popular support. And among its smaller achievements the Constitution Act, 1982 changed the name of the old British North America Act to the Constitution Act, 1867. (If you think this means we more or less have two main written constitutions in Canada now – an old one and a new one – you are not entirely wrong.)

There are some who say that, except for matters dealing with the federal government alone, this procedure has proved so demanding as to make the present Constitution of Canada engraved in stone. But the Charter has won great popular support. And among its smaller achievements the Constitution Act, 1982 changed the name of the old British North America Act to the Constitution Act, 1867. (If you think this means we more or less have two main written constitutions in Canada now – an old one and a new one – you are not entirely wrong.)

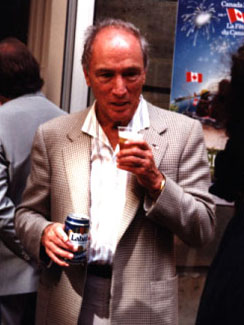

Pierre Trudeau played such a leading role in the achievement of the Constitution Act, 1982 – in the wake of the first failed Quebec sovereignty referendum, of 1980 – that the present Harper government in Ottawa has been reluctant to do much by way of celebrating its 30th anniversary. When you think of Mr. Harper’s recent neo-colonial enthusiasms for reviving the Royal Canadian Navy and whatnot, something deeper than Trudeau-envy may be at work as well.

Pierre Trudeau played such a leading role in the achievement of the Constitution Act, 1982 – in the wake of the first failed Quebec sovereignty referendum, of 1980 – that the present Harper government in Ottawa has been reluctant to do much by way of celebrating its 30th anniversary. When you think of Mr. Harper’s recent neo-colonial enthusiasms for reviving the Royal Canadian Navy and whatnot, something deeper than Trudeau-envy may be at work as well.

“The Constitution Act, 1982,” the political scientist Frederick Vaughan has written, “was the instrument that, with one stroke, severed Canadians from their ancestral monarchical foundations. With the Charter Canada began a new life as a nation. The Charter is based upon republican principles. It is the closest Canadians have ever come to a document that affirms the rights of the people.”

In his remarks on April 17, 1982, from underneath the covered dais, Pierre Trudeau declared “no Constitution, no Charter of Rights and Freedoms … can be a substitute for the willingness to share the risks and grandeur of the Canadian adventure … Let us celebrate the renewal and patriation of our Constitution; but let us put our faith, first and foremost, in the people of Canada who will breathe life into it.” And, he concluded, it was in the name of “Canadians everywhere” that he invited Queen Elizabeth II “to give solemn proclamation to our new Constitution.”

In his remarks on April 17, 1982, from underneath the covered dais, Pierre Trudeau declared “no Constitution, no Charter of Rights and Freedoms … can be a substitute for the willingness to share the risks and grandeur of the Canadian adventure … Let us celebrate the renewal and patriation of our Constitution; but let us put our faith, first and foremost, in the people of Canada who will breathe life into it.” And, he concluded, it was in the name of “Canadians everywhere” that he invited Queen Elizabeth II “to give solemn proclamation to our new Constitution.”

Inevitably, the constitutional achievement of Pierre Trudeau and the federal and provincial politicians of the early 1980s elected by the people of Canada was far from perfect. The risks and grandeur of the Canadian adventure continue. Both the Constitution Act, 1867 and the Constitution Act, 1982 need to be extended on several different fronts. (Not the least of which, of course, is Quebec’s continuing official refusal to “sign on” to what happened on April 17, 1982!) To believe in the long-term future of the Canadian adventure is to believe that, at some point soon enough, at least some of the most important things that still need to be done will get done.

Meanwhile, here are a half dozen recent newspaper articles and commentaries on the 30th anniversary: “Canada’s cherished Charter could not have happened without ‘kitchen accord’” ; “If the War of 1812 warrants commemoration, so does the patriation of the Constitution: Chretien” ; “Constitutional rift between Quebec, rest of Canada left a ‘deep scar’” ; “Why this year could prove to be the Charter’s most controversial” ; “Thatcher cabinet looked at rejecting Canadian Charter of Rights plan” ; and (as just one reminder of what still needs to be done) “Trudeau, c’est Wolfe!” As usual, this is Canada, and there are many points of view. But I’ve been around for more than six decades now. And the Constitution Act, 1982 is still the biggest thing that has happened to Canada in my lifetime. Before April 17, 2012 is over, I’m going to drink as much as I can from a very large bottle of champagne.

Meanwhile, here are a half dozen recent newspaper articles and commentaries on the 30th anniversary: “Canada’s cherished Charter could not have happened without ‘kitchen accord’” ; “If the War of 1812 warrants commemoration, so does the patriation of the Constitution: Chretien” ; “Constitutional rift between Quebec, rest of Canada left a ‘deep scar’” ; “Why this year could prove to be the Charter’s most controversial” ; “Thatcher cabinet looked at rejecting Canadian Charter of Rights plan” ; and (as just one reminder of what still needs to be done) “Trudeau, c’est Wolfe!” As usual, this is Canada, and there are many points of view. But I’ve been around for more than six decades now. And the Constitution Act, 1982 is still the biggest thing that has happened to Canada in my lifetime. Before April 17, 2012 is over, I’m going to drink as much as I can from a very large bottle of champagne.