175th anniversary of 1837 rebellions more important for Canadian democracy today than War of 1812

Dec 4th, 2012 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage NowA recent poll on the pride Canadians place in more than a dozen symbols and achievements found that the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812 this year came in near the bottom – even though the federal government has budgeted more than $28 million to mark the occasion.

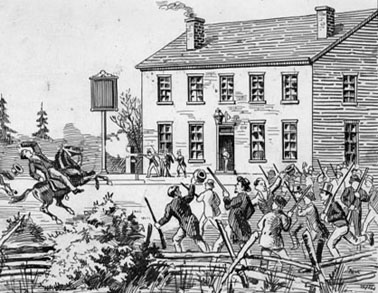

The 175th anniversary of the so-called Battle of Montgomery’s Tavern in the ill-fated Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837 – this coming Friday, December 7, 2012 – was not something the pollsters considered. But the Rebellion almost certainly contributed more to the Canadian democracy we enjoy today than the War of 1812.

For the moment the site of Montgomery’s Tavern, on Yonge Street in Toronto, just north of Eglinton, is occupied by a two-storey Art Deco post office built in 1936. Local residents have been protesting Canada Post’s recent sale of the building, without any guarantee for preserving its historic significance.

Some will rightly enough stress that the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, led by the “firebrand” first mayor of Toronto, William Lyon Mackenzie, was a less than glorious military episode in the international struggle for what our Constitution Act 1982 calls the “free and democratic society.”

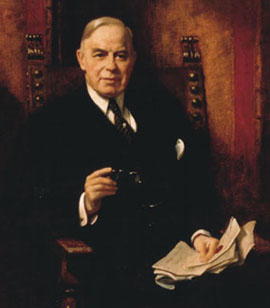

William Lyon Mackenzie was the grandfather of William Lyon Mackenzie King – still Canada’s longest serving prime minister, in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. And Mackenzie King’s unique approach to the arts and crafts of democratic government was summarized in the slogan “conscription if necessary but not necessarily conscription,” during the debate on compulsory military service in the Second World War.

From some points of view, the rebel leader William Lyon Mackenzie was at the opposite end of some human spectrum from his grandson William Lyon Mackenzie King. In other ways the two men had more in common than is usually thought. A “rebellion if necessary, but not necessarily a rebellion” is an apt enough characterization of the 1837 rebellion in Upper Canada.

Yet, whatever else, 1837 set the stage for the achievement of so-called “responsible government” just over a decade later in 1848. And this marks the practical beginning of our modern Canadian parliamentary democracy.

* * * *

In the early 21st century, our collective institutional memory of the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837 in what is now Ontario – and its companion Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837—38 in what is now Quebec – may be even weaker than our memory of the War of 1812.

On the 100th anniversary of the rebellion in 1937, however, the historian Stanley Ryerson (a descendant of the Egerton Ryerson after whom today’s Ryerson University is named) published a book called 1837: The Birth of Canadian Democracy.

In the same year Prime Minister William Lyon Mackeznie King spoke at the unveiling of a memorial arch in Niagara Falls honouring his grandfather “and his associates in the Rebellion.” The prime minister, “while lauding Mackenzie and those associated with him in the battle for freedom in Canada … declared that even more deserving of praise were the common people of that day, people whose names are not written in the nation’s annals …”

A decade later, when his Canadian history textbook Colony to Nation first appeared, the historian Arthur Lower wrote that William Lyon Mackenzie and his fellow Upper Canada rebels “stood for … the many against the few, for democracy against privilege.”

On the 175th anniversary of the Rebellion in 2012, there are at least a few encouraging signs that this side of our collective institutional memory may be starting to come back.

One of the top four symbols and achievements in which pollsters have recently found that Canadians take pride is the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution Act 1982. And as the political scientist Frederick Vaughan urged a few years ago, the “Charter … is the closest Canadians have ever come to a document that affirms the rights of the people.”

In this sense our 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms is itself a legacy of the Canadian rebellions of 1837—38. The current efforts of local residents to preserve something of the historic significance of the site of Montgomery’s Tavern are similarly encouraging.

If you are anywhere near this site – on Friday, December 7, 2012 or anytime between December 4 and December 7, when various ill-fated rebel enterprises unfolded – you might raise a glass of something to William Lyon Mackenzie and his associates. (And even more to Mackenzie King’s common people of that day, who played their own role in making the Canadian democracy we are still so lucky to enjoy 175 years later, on the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812.)