How two early January 2013 events show that the British monarchy in Canada is living on borrowed time ..

Jan 11th, 2013 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In Brief

Teenage Lady Diana Spencer on a Swiss ski vacation, taken about a year before she met Prince Charles. Two days after her engagement to the Prince, the Daily Mirror purchased this photo from a scandal-monger. But the editor decided not to publish it. It finally hit the news early this year, in 2013. The gentleman with Ms Spencer is apparently Adam Russell, great-grandson of former British prime minister Stanley Baldwin,

Still strangely enthralled by legendary Tory oligarchs of the 19th century, the mainstream media usually tries hard not to notice. But there is nonetheless an ardently gurgling Canadian republican activism even in various anglophone parts of the country in the early 21st century.

This activism has a number of reasons for wanting to retire the current very last vestiges of the British monarchy in Canada today – in favour of a new Canadian republic, that takes the quiet but impressive allusion to our present “free and democratic society”in the Constitution Act, 1982 as its fundamental point of departure, in both practice and theory.

One of the largest inspirations for our own Canadian republican faith on this site is the sheer fantasyland overtones of the contention that, although Canada today has no continuing colonial relationship with the United Kingdom, the monarch of this Kingdom (currently a dutiful octogenarian Queen of course) somehow remains the Canadian head of state.

(As it still says in our other and older and in this respect still unamended “written” constitution, so to speak, the Constitution Act, 1867 : “Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom,” etc, etc, etc.)

1. “A daughter for Will and Kate could create a royal headache” in Canada …

The new year of 2013 has barely begun. And already we have before us two quaint examples of just how difficult it is to make any constructive, forward-looking sense out of Canada’s continuing alleged relationship with the monarchy in Buckingham Palace across the sea.

The first is a January 3, 2013 article on the Macleans.ca website : “A daughter for Will and Kate could create a royal headache … Colby Cosh on the Constitutional problem of a female heir.”

This article notes that with “the wife of HRH Prince William” now “great with child,” the British government has legislation ready to go “that will allow the Prince’s children to succeed in order of seniority, irrespective of sex.” And like the other remaining so-called “Commonwealth realms” that share the British monarch with the United Kingdom (Australia etc), we in Canada have parallel legislation for our own “federal Parliament, and the government has a promise of enthusiastic support from the New Democratic Opposition.”

Alas, in the dying days of 2012 “a couple of troublemakers–University of Ottawa professor Philippe Lagassé and graduate student James Bowden–took to the pages of the Ottawa Citizen to chirp a warning …. the Constitution Act of 1982 says that any amendment to Canada’s Constitution ‘in relation to the office of the Queen’ has to have the unanimous consent of the provincial legislatures as well as the Senate and the House of Commons.”

Mr. Harper’s government is apparently saying that this provision of the 1982 Constitution Act does not apply in this case. But it certainly seems to us that it does – although we agree that this somewhat bizarrely complicates our Canadian version of allowing “the Prince’s children to succeed in order of seniority, irrespective of sex.”

And who knows? This could even lead to an argument that, if the required unanimous provincial approval is not obtained – and present plans in Canada apparently envision that it will not be obtained – a female heir of HRH Prince William would no longer qualify as Canadian head of state. (And, if no other prior means has arisen by the future time in question, we, like others no doubt, would certainly support this argument as a constitutional approach to at last retiring the British monarchy in Canada!)

2. Yes … it probably won’t happen, but the key point is that it could!

Some say female heirs to the English throne have a pretty good track record. But this is not the case for “Bloody Mary,” Queen of England , 1553—1558.

You can of course quite rightly urge that it will be some time yet before anything like this could happen – even assuming that the first child of HRH Prince William and the Duchess of Cambridge actually is a female and not a male.

And we would much prefer ourselves to see a Canadian republic arise in a more sensible and overtly free and democratic way. (Via a proper constitutional amendment that includes unanimous provincial approval, following a decisive popular victory in a Canada-wide referendum, eg.)

Yet it remains true that the troublemakers Philippe Lagass̩ and James Bowden have shown just how mysteriously tenuous the fantasyland theory of the British monarchy in Canada has already become Рand how susceptible it is to sudden creative destruction on obscure metaphysical grounds.

(Ardent monarchists who want to ensure the institution’s long-term future in Canada should be arguing that unanimous provincial approval of any changes in the current succession rules is absolutely necessary now! But if they are, it is very hard to hear them.)

3. “We have sent a letter to Buckingham Palace … requesting that Queen Elizabeth II send forth her representative, which is the governor general of Canada” …

Attawapiskat First Nations Chief Theresa Spence leaves Victoria Island as she continues her hunger strike in Ottawa, Wednesday January 9, 2013. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Fred Chartrand.

A more serious and immediate illustration of the increasingly shaky ground on which the British monarchy in Canada stands has arisen over the past week or so, in connection with the wave of protest from assorted aboriginal peoples of Canada that has also greeted the New Year of 2013 in the most northern parts of North America.

This past Wednesday, the hunger-striking Chief Theresa Spence of the Attawapiskat First Nation declared that she “will not attend the Friday meeting between Prime Minister Stephen Harper [on aboriginal issues in Canada today] unless Governor-General David Johnston decides to go.”

Chief Spence went on:”We have sent a letter to Buckingham Palace … requesting that Queen Elizabeth II send forth her representative, which is the governor general of Canada. I will not be attending Friday’s meeting with the Prime Minister, as the governor general’s attendance is integral when discussing Inherent and Treaty Rights.”

The argument here was further elaborated in a news release from “Spence spokesman Danny Metatawbin … ‘This is a time of crisis and this government of the day is not taking Indigenous Peoples concerns seriously … We are sending messages to the Queen. Canada should take notice and act honourably’”

Attawapiskat First Nations Chief Theresa Spence with Danny Metatawabin on Victoria Island, December 27, 2012.

Mr. Metatawbin went on, noting that certain key aboriginal “treaties were made under the Royal Proclamation of 1763.” He “argued that since” these treaties “allowed for settlement in aboriginal territories, the legitimacy of the country rests on the treaties … If the state of Canada continues to undermine and destroy the treaty relationship, what rights does Canada have to exist within our territories?”

All this, it seems to us, points to an increasingly destructive fantasy at the bottom of much current thinking about Canada, on the part of various self-appointed leaders of what the Constitution Act, 1982 calls the aboriginal peoples of Canada. And it is part of Mr.Harper’s current dilemma on aboriginal issues that he has aided and abetted this fantasy himself.

4. It is the Canadian people and not the British monarchy that the aboriginal peoples of Canada need to be negotiating with today …

Pontiac, War Chief of the Ottawa, led the astonishingly successful “French and (mostly) Indian” wilderness protest against the so-called British conquest of Canada, in the spring and summer of 1763.

At the bottom of this fantasy is the notion that aboriginal peoples negotiated their current status in Canada as “sovereign”nations, dealing with the British Crown – with special emphasis on the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

What is less often spelled out is that the British Royal Proclamation of 1763 tried to bring some kind of benign conclusion to a great protest of northern North American first peoples, known as the Conspiracy of Pontiac or Pontiac’s Rebellion, at the end of the Seven Years War, which transferred effective European sovereignty in Canada from France to Great Britain.

The current theory of the British monarchy’s continuing role in Canadian aboriginal issues entertained by Chief Spence and other aboriginal leaders not only ignores Pontiac’s historic protest, that finally crystallized the Royal Proclamation of 1763. It also ignores the previous century and a half of “French and Indian” collaboration in the early growth and development of modern Canada (to say nothing of the plain truth that “Canada” itself is an aboriginal word).

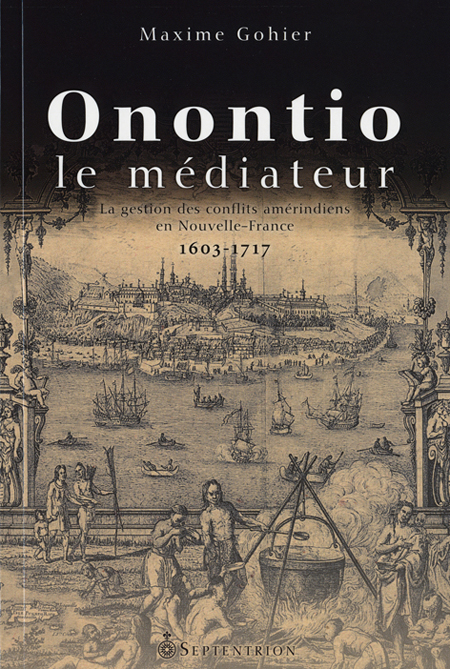

Another book on the role of the role of the Governor at Quebec City in promoting the French and Indian alliance that “preserved Canada” in the later 17th and earlier 18th centuries – Onontio le médiateur, by Maxime Gohier. “Dans son récit intitulé Des Sauvages, Champlain résume ainsi la politique que la France entend mettre en oeuvre en Amérique du Nord. Tous les administrateurs après lui allaient poursuivre, tant bien que mal, un même objectif : établir et maintenir une paix générale entre toutes les nations autochtones.”

The American historian Richard White, eg, has recently captured the crux of this collaboration in his path-breaking study of 1991 on The Middle Ground : Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650—1815. As White explains : “Out of the French and Algonquian triumph over the Iroquois there evolved during the eighteenth century a Janus-faced alliance” between the northern Algonquians and “Onontio, the French governor at Quebec.” It was this alliance that, in the midst of much seething and often bloody conflict, ultimately “preserved Canada” in the Great Lakes and finally allowed the early Canadian fur trade to venture still further west, almost to the Rocky Mountains by the middle of the 18th century.

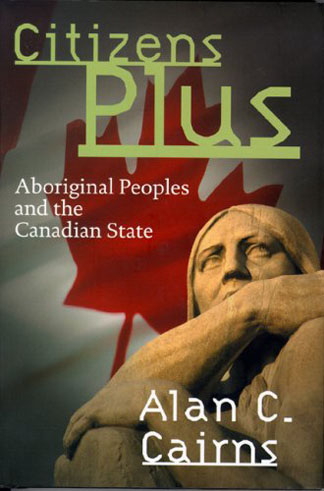

Still more to the point for the here and now in 2013 is a quotation from the conclusion of the Canadian political scientist Alan C. Cairns’s path-breaking study of 2000, Citizens Plus : Aboriginal Peoples and the Canadian State : “The momentum behind the drive to self-government and the support for the positive recognition of the Aboriginal presence in Canada are irresistible imperatives to which a whole-hearted ‘Yes’ is the only answer. On the other hand, the conditions that sustained the nation-to-nation relations of the early contact period have vanished. Our nation-to-nation relationship then was international. It is not so now and hence to so describe it even if only implicitly, without qualification, risks a damaging confusion.”

Still more to the point for the here and now in 2013 is a quotation from the conclusion of the Canadian political scientist Alan C. Cairns’s path-breaking study of 2000, Citizens Plus : Aboriginal Peoples and the Canadian State : “The momentum behind the drive to self-government and the support for the positive recognition of the Aboriginal presence in Canada are irresistible imperatives to which a whole-hearted ‘Yes’ is the only answer. On the other hand, the conditions that sustained the nation-to-nation relations of the early contact period have vanished. Our nation-to-nation relationship then was international. It is not so now and hence to so describe it even if only implicitly, without qualification, risks a damaging confusion.”

The present-day symbolic fantasy of the British monarchy’s unique responsibility for the aboriginal peoples of Canada and what Chief Spence calls their “Inherent and Treaty Rights” has already begun to show just how damaging this kind of confusion can be, in very practical ways.

Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Grand Chief Derek Nepinak has “warned Harper to meet the demands of aboriginal leaders and the Idle No More protest movement, which he said would involve nothing short of a transformative nation-to-nation relationship based on respecting treaty rights, or else ‘warriors’ were ready to ‘bring the Canadian economy to its knees’.”

Someone needs to point out to Chief Spence and the aboriginal leaders who share her current rhetoric just how the role of the monarchy in Canada today is defined, eg, in Richard Van Loon and Michael S. Whitington’s now classic Canadian government textbook, first published in 1971: “the formal executive power in Canada is vested in the Crown, and in a very formal sense, we can be said to have a monarchical form of government. The Governor General exercises all of the prerogative rights and privileges of the Queen in right of Canada, according to the BNA Act [now called the Constitution Act, 1867] and the Letters Patent that define his office. The constitutional doctrine of popular sovereignty has, however, reduced the de facto role of the Governor General to that of a figurehead. The real power is exercised by the Prime Minister and his cabinet who obtain their legitimacy from the fact that they possess a popular mandate.”

Still more to the most crucial point in 2013, if Canada’s aboriginal leaders want to make real and sustained progress on the “momentum behind the drive to self-government and the support for the positive recognition of the Aboriginal presence in Canada,” they have to stop pretending that the Queen Elizabeth II who lives in Buckingham Palace across the sea has any practical authority over what happens in Canada today. They have to start talking with the sovereign Canadian people, who do have this authority – and who become understandably alarmed and antagonized when they read that “Grand Chief Derek Nepinak warned Harper to meet the demands of aboriginal leaders and the Idle No More protest movement, which he said would involve nothing short of a transformative nation-to-nation relationship based on respecting treaty rights, or else ‘warriors’ were ready to ‘bring the Canadian economy to its knees’.”

As with the vaguely parallel case of the Quebecois nation in a united Canada, this kind of dialogue is complicated by the thorny fact that the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are also part of the Canadian people themselves (or as Alan Cairns put it, the aboriginal peoples of Canada are “charter members of the Canadian community”). And it is much easier to pretend there is a Queen somewhere, who just has to do what you want, or who can somehow command what Alan Cairns also called “the non-Aboriginal federal and provincial majorities” to (in the words of Danny Metatawbin) “take notice and act honourably.”

Yet it seems altogether clear to us that real practical progress on “the positive recognition of the Aboriginal presence in Canada” will never happen until the Aboriginal peoples of Canada and the Canadian people actually start engaging in some constructive dialogue.

Prime Minister Harper’s own (here as elsewhere) partisan and divisive efforts to somehow revive the fading old colonial and elitist institution of the British monarchy in Canada is not helping to even get some dialogue of this sort barely begun.

Prime Minister Harper’s own (here as elsewhere) partisan and divisive efforts to somehow revive the fading old colonial and elitist institution of the British monarchy in Canada is not helping to even get some dialogue of this sort barely begun.

We certainly agree as well that we the Canadian people still have many things to learn about our own real Canadian history, and the role of aboriginal peoples in this history. But our very final view is that any serious and enduring positive recognition of the Aboriginal presence in Canada will only happen hand in hand with the rise of a new Canadian republic, that takes the quiet but impressive allusion to our present “free and democratic society”in the Constitution Act, 1982 (which also recognizes the “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada”) as its fundamental point of departure, in both practice and theory. What today’s ardently gurgling Canadian republican activism needs in this respect (and vice-versa of course) are some equally ardent Canadian aboriginal partners.