“A democrat is liable to change his mind a lot” .. discovering the American West of Edward Dorn

May 5th, 2013 | By Citizen X | Category: USA TodayI was quite deeply into reading poetry (or verse, as some said), from about my late teens to my early 20s. Then the practicalities of life pushed me in other directions. I returned for a brief time in my late 30s. But fate again conspired to focus my thoughts on the more prosaic realities of business and politics – so much more admired on the street where I lived.

Now in my late 60s I know very little about more recent English language poets. Perhaps far too chauvinistically, I have tended to assume that poetry generally is not as important as it used to be – because I am not reading it the way I used to. When I read reviews of more recent poets’ work, as I still occasionally do, they often seem to confirm both my own and my assumed wider reading community’s growing lack of interest.

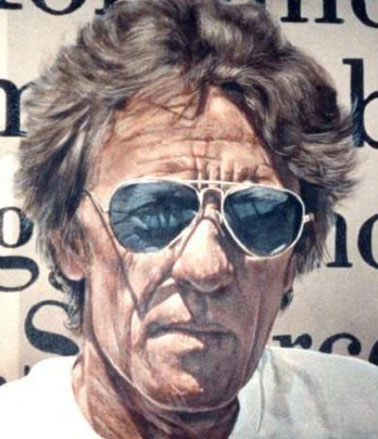

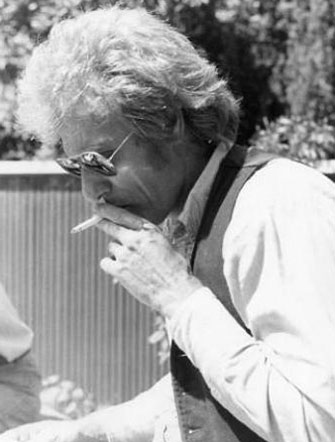

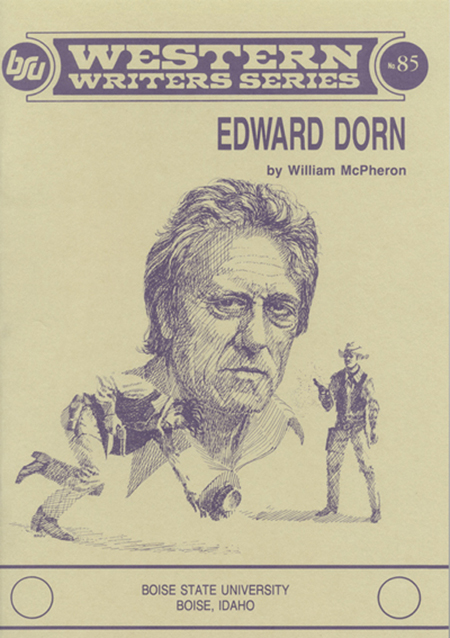

Yet, just a few weeks ago, reading Iain Sinclair’s review of Collected Poems by the late Edward Dorn (1929—1999), in the 11 April 2013 issue of the London Review of Books, has almost changed my mind. I have at any rate started thinking that I may catch up on a little of what I have missed, by delving into the poetry of “Ed Dorn” – who was born poor in small-town Illinois, somehow managed to attend Black Mountain College in North Carolina, taught for a time at Idaho State University in the far American West, moved to Essex University in the UK for five years, and finally landed at the University of Colorado at Boulder, after his magnum opus, Gunslinger, appeared in print.

The new 2012 edition of the Collected Poems, edited by Dorn’s second wife, Jennifer Dunbar Dorn, with the help of a few other colleagues, weighs in at just under 1,000 pages. Patrick McGuinness at the Guardian recommends that : “For the reader coming to Dorn for the first time, and faced with a book this long and this unusual, there are three good places to start, none of which is the beginning: the love poems of Nine Songs (1965), the first book of his psychedelic cowboy epic Gunslinger (1968), and the posthumously published Chemo Sabé (2001), in which the dying poet describes his cancer against the background of the Clinton impeachment and American foreign policy adventures.”

1

For me in the year 2013, even wading through Iain Sinclair’s London Review of Books piece on the new almost 1,000 page volume of Dorn’s verse was not exactly easy. And it was a while before I started thinking “Eureka” – I have just found something fresh and new, to wake up and re-charge my aging brain.

I was urged along by rising numbers of intriguing strings of words, that promised further connections with things I identify with. The process began when Sinclair quoted from one of Ed Dorn’s poems: “She’s like Wittgenstein’s lunch, utterly invariable …” I have almost no idea what this really means. But I have the two key Wittgenstein books on my shelves, and at one point I actually tried to understand them. Maybe Ed Dorn understood Wittgenstein. (And, according to Luis Miguel Diaz : “After exhausting philosophical work Wittgenstein would often relax by watching a western movie, where he preferred to sit at the very front of the cinema.”)

Then Sinclair quoted Dorn’s fellow poet J.H. Prynne, who commented on Dorn’s fine ear “for spoken English and for the cadences of English speech, both grand and passionate, and ordinary off the street.” Then Sinclair alluded to Dorn’s “lifelong engagement with the American West,” and pointed out how Dorn was “a tough but delicately nuanced geographer, a discriminator of landscape.” Then Sinclair quoted from another poem of Dorn’s, which spoke of “California stiff-as-a-board sensibility.” (I have just enough experience of California, maybe, to imagine that this captures something about the place I have felt, but been unable to articulate.)

I was intrigued as well by Sinclair’s account of the poetry publishing milieu in which Edward Dorn’s writing first emerged. It was a US-UK universe, in which “poets published poets, signalling their affinities the best way, through production, while continuing to strengthen transatlantic traffic, through readings, academic exchanges, hospitality. Distribution was nicely random, with many of these books and pamphlets being trusted to the postal service, as gifts to peers, known and unknown.” It was a small world in which “a certain kind of book, produced by poets, and frequently published by them, and delivered to a modest audience of fellow practitioners, could exist and thrive only in a culture of small independent shops … operating at the outer limits of the possible.” (And then I think, making excuses for myself : no wonder readers like me lost touch with this kind of poetry. But perhaps I have just been too lazy?)

2

Patrick McGuinness’s “Collected Poems by Edward Dorn — review,” in the 1 February 2013 issue of the Guardian is probably somewhat more accessible (for many readers at least) than Iain Sinclair’s more complex piece in the London Review of Books.

McGuinness rather nicely begins with : “‘You don’t disappear. You reappear, dead,’ wrote Ed Dorn, who died in 1999 and emphatically reappears here: nearly 1,000 pages of poetry ranging over almost 50 years of work. Born in Illinois in 1929, Dorn grew up in rural poverty in what he described, in his 1969 autobiographical novel By the Sound, as ‘the basement stratum of society’. He was associated with Black Mountain poets Robert Creeley and Robert Duncan, writers who, like Dorn, took their early bearings from Charles Olson.”

McGuinness also offers an entertaining (and illuminating) summary or short introduction to Edward Dorn’s magnum opus : “Gunslinger is perhaps the strangest long poem of the last half-century: a quest myth wrapped around an acid-inspired western comic strip adventure in which a gunslinger, astride a drug-taking, talking horse called Levi-Strauss, searches for Howard Hughes (‘they say he moved to Vegas / or bought Vegas and / moved it. / I can’t remember which’). Charles Olson had insisted, in the wake of Pound, that where Europe had history to make poetry with, America must take geography. Dorn’s contribution to the Great American Long Poem – Pound’s Cantos, WC Williams’s Paterson, Olson’s Maximus … – was Gunslinger, which appeared in five sections over six years. The American west was Dorn’s imaginative home, and his poem is an extraordinary feat of imagination, humour, allusion and lyric invention. It takes the standard fare of a good if surreal western (brothel madams, saloon brawls and gunfights) and melds it with high philosophical riffs.”

The last paragraph of Patrick McGuinness’s Guardian review of the Collected Poems alludes to the compelling political side of Edward Dorn’s work : “Dorn was a radical and a heretic, and his late poems are concerned with heretics and their persecution by states, governments and official religions. In a late reading in London, as he discussed Languedoc Variorum – a sequence which, with typical Dornian dual-time parallel vision, explores the suppression of the Cathars and Albigensians alongside today’s religious turmoil –Â he was asked why he thought heretics were persecuted. His answer –Â that heretics are the only ones who really care about religion – gives us an insight into his humour, the breadth of his sympathy, and the integrity of his poetry. This book is enormous, but it is navigable and enriching in all sorts of ways: what you get from Dorn is not available anywhere else in poetry.”

3

There is, it often seems, a kind of at first glance strange symbiosis between what might be somewhat crudely called Old World Anglo Saxonism and the American West. (Think, eg, of the connections between Cyril Connolly’s UK literary legacy and the Universities of Texas and Tulsa, and of Larry McMurtry’s literary interest in the English aristocracy.) And it seems likely enough that the five years Ed Dorn spent “in England, where, invited by the poet and critic Donald Davie, he taught in the English department at the University of Essex,” were no accident.

There is, it often seems, a kind of at first glance strange symbiosis between what might be somewhat crudely called Old World Anglo Saxonism and the American West. (Think, eg, of the connections between Cyril Connolly’s UK literary legacy and the Universities of Texas and Tulsa, and of Larry McMurtry’s literary interest in the English aristocracy.) And it seems likely enough that the five years Ed Dorn spent “in England, where, invited by the poet and critic Donald Davie, he taught in the English department at the University of Essex,” were no accident.

The growing heretical reputation that apparently haunted Dorn’s later career may have some misleading or even mistaken connections here as well. Iain Sinclair devotes much of the later part of his London Review of Books piece to explaining all this. He tells us that : “The visceral excitement palpable in the performance of the writing of Gunslinger, supremely a work of its moment [late 60s/early 70s], faded. Dorn recognised early the bleakness of the 1980s.”

Sinclair goes on : “He chose not to publish for much of this period, but to assemble instead, from an amused and alarmed scrutiny of newsprint … whips and scorpions of electively intemperate satire. ‘My tongue has been/my genius and my downfall,’ Dorn said. The position was not popular and he took pride in that … ‘Mediocrity rises to the top in America like cream on milk, and it always has,’ he remarked. ‘If you’re a writer who lets these things bother you, you’re in the wrong business’ …Â The coming gossip-stew of the internet didn’t help. ‘Email is MEmail,’ Dorn reckoned. Private remarks or classroom provocations went virally rancid as he was whistled and gibed at for his scorn towards all manifestations of political correctness. Multiculturalism in most of its discursive forms, Dorn said, was ‘the cult par excellence of late imperialism’, dogma customised to serve the agendas of strategic internationalism.”

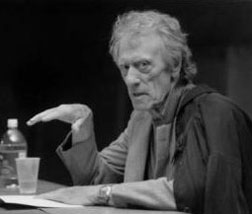

Remarks of this sort did not go down well in late 20th century academia at the University of Colorado at Boulder, where Edward Dorn’s professional career finally landed. In his lectures Dorn wound up “saying more and more outrageous things.” Some of his “poetry students,” keen to “do anything they think will help locate themselves and give themselves some minimal celebrity,” began to “spew back reports of things he said. And distorted, illiterate, stupid versions. And that began the process that led to the noose being put around his neck.” Dorn himself remarked : “It’s a lot easier to be a heretic than it used to be … There are more religions willing to kill you.”

4

Nowadays, getting close to a decade and a half after Edward Dorn’s death from cancer, some two weeks before Christmas 1999, the absurdities of late 20th century political correctness have themselves begun to fade. And the deeper truths of both his real passion for American diversity and his transatlantic anglospheric connections (which he continued to cultivate, almost to his death) are starting to become clearer. The heretic of the past grows closer to the present anti-hero.

And so we can now start to see more clearly, Iain Sinclair also takes pains to stress, how Edward Dorn shaped Howard Hughes’s “non-existence into a divine comedy of cocaine and cactus; virtual travel through high sierras and white deserts zeroing towards the vanishing line of the horizon like the bad craziness of a Monte Hellman western.”

Similarly, Sinclair urges, the “compacted meteorite of the Dorn Collected Poems, so rich and dense, now bombed into our cultural badlands, offers spectacular rewards, as the strategic shifts and heretical inspirations of the poet’s long career are revealed … He mastered a ‘terrific actualism’ … looking at the land with an eye trained by Olson and by the geographer Carl Ortwin Sauer … Dorn would launch one of his seminars by unrolling a railroad map of the US, which showed the sections awarded to the piratical magnates of the 19th century by giveaways of public land. He identified, most powerfully, with the Apache, the warrior remnants of the southwest.”

In the end : “The grand mythopoeic structures of Pound and Olson, magnificent but unresolved, beacons of high modernism, were succeeded by Dorn’s synapse-frying Lenny Bruce performance … Dorn sculpted Gunslinger from the cast of John Ford’s Stagecoach sent out on the road to nowhere (or Las Vegas) in a chemically induced haze … The timelessness of New Mexico’s bandit opportunism means that Dorn’s characters fit very comfortably into the world of the [celebrated present-day] TV series Breaking Bad … Dorn, forty years ahead of the game, exploited that clarity of light, where bad things have a hyper-real outline and the borders between countries and states of consciousness are dangerously porous.” And Iain Sinclair ends his London Review of Books piece with a last highly provocative quotation from the works of Edward Dorn, who was obsessed by the American West: “I have to be there with the Indians. I don’t have a country any more than they do.”

5

I have stumbled across a few more intriguing things about the career of Edward Dorn, in my own initial quick and dirty travels among Iain Sinclair’s “gossip-stew of the internet.”

To start with, the Wikipedia article on”Ed Dorn” is not without some interest. It quickly sketches his life and lists his publications, and some internet resources. It also notes that : “Popular horror novelist Stephen King admired Dorn, describing his poetry as ‘talismans of perfect writing’ and even naming the first novel of The Dark Tower series, “The Gunslinger,” in honor of Dorn’s poem. King also opened both the prologue and epilogue of “The Stand” with Dorn’s line, ‘We need help, the Poet reckoned.’”

The publisher’s blurb for the 2012 Collected Poems has some interest as well: “For the first time the vast, experimental totality of Gunslinger poet Edward Dorn’s work is collected in a single volume. After studying with Charles Olson at Black Mountain College, Dorn took on the American West, developing an unmistakable voice, ‘as evocative as a lonesome train whistle in the night’. Olson praised his ‘Shakespearean ear for syllables’. Taking his bearings from Pound and Williams, he found his own way, a pioneer in the old American way …. Peter Ackroyd considers him ‘the only plausible, political poet in America […] one of the masters of our contemporary language.’”

Finally, as an illustration of just what it means to say that the late Edward Dorn is/was “the only plausible, political poet in America,” consider this passage from the Poetry Foundation website: “When asked about his poetic critique of America for its imperialism, its carelessness with the environment, and its treatment of minorities, Dorn once remarked: ‘I take democracy very seriously, but on the other hand, it’s a form of government that you have to change your mind about a lot because its form is protean, and its instinct, essentially, comes from a mob psychology. Unlike an adherent to a dogmatic position like Marxism, about which there is very little to change your mind, a democrat is liable to change his mind a lot. So none of these concerns and principles ever leave my mind much, but I vary my attitude according to the angles of perspective I’m able to get on them. Democracy literally has to be cracked on the head all the time to keep it in good condition. But all other forms are more or less sudden death.’”

6

Fairly early on in his recent London Review of Books piece, Iain Sinclair refers to “Tom Clark, another itinerant US poet and Essex academic.” In my initial quick and dirty travels among the “gossip-stew of the internet,” I have happily bumped into a website called “Tom Clark – Beyond the Pale.” And a 30 September 2011 entry on this site reproduces an Edward Dorn poem called “A Vague Love,” from the 1968 edition of a publication called Geography.

Mr. Clark spells out : “Please note that the poems and essays on this site are copyright and may not be reproduced without the author’s permission.” If I could find a convenient email address for him on his site. I might actually try to get in touch. Though how he would hold the copyright on one of Ed Dorn’s poems is a mystery to me.

I am in any case grateful indeed for Tom Clark’s website, and I think “A Vague Love” tidily illustrates many of the contentions about Edward Dorn the poet that appear above. And while I have serious plans to purchase Dorn’s Collected Poems very soon (I would have it already, if the Amazon Canada site were not quite so complicated), for the time being I am pleased to end my quick and dirty introduction here with a sample of Ed Dorn’s work (with both apologies and thanks to Tom Clark, if he ever somehow stumbles across this page in cyberspace). I should just altogether finally note that the “Bannocks” referred to in this Ed Dorn poem are a group of Native Americans:

The Bannocks stand by the box.

They sway to the music.

A California truck driver

in with a load of pianos

shoots pool.

Their women

are not beautiful

they are not

but their eyes

have deep corridors in them

of brown hills of pain and

indecision and under every

lash

is a question no man, not

even their own

can answer.

Where is the deer?

That is not the question.

tic tok, stop de clock.

sings Fats Domino.

We all stand swaying.

it’s someone’s turn to shoot.