Istanbul Revisited 2013

Jun 17th, 2013 | By Citizen X | Category: Countries of the WorldAs I start to write here in northern North America, the headlines from the old heartland of the Ottoman empire far away, between the Mediterranean and Black seas, are not encouraging.

(See : “Police lock down Taksim, PM shows off in Istanbul” ; “Turkish PM says it was his ‘duty’ to oust protestors occupying Istanbul park” ; “Turkish protesters kept away from Taksim Square by police” ; and “Turkish riot police crack down on protesters.”)

I take some solace from “Why Turkey protests are a good thing” by Fareed Zakaria – posted on the CNN website this past Friday. But I can’t pretend to have any idea about what will finally happen. And it seems that, whatever else, things are getting worse before they get better.

The news fills me with a quiet sadness. To start with, I spent two enchanted-tourist days in Turkey not quite half a dozen years ago, in Izmir and Istanbul. Now the current “Descent into confrontation” seems to be stealing some of my warmest recent memories of public spaces in the global village – and even a few upbeat thoughts about the future for our troubled species.

And then if some ultimate (almost religious?) faith in democracy is especially important to you, the current descent in Istanbul and other parts of Turkey is bound to point towards some deeper summer of discontent.

The descent began in the “last week of May 2013” when “a group of people most of whom did not belong to any specific organization or ideology got together in Istanbul’s Gezi Park.” Their immediate object was to “prevent and protest the upcoming demolishing of the park for the sake of building yet another shopping mall at very center of the city.”

Sumandef Hakkinda, a young lady on the spot, has told her version of the story from here: The “police arrived with water cannon vehicles and pepper spray. They chased the crowds out of the park …Â In the evening of May 31st the number of protesters multiplied. So did the number of police forces around the park. Meanwhile the local government of Istanbul shut down all the ways leading up to Taksim square where the Gezi Park is located. The metro was shut down, ferries were cancelled, roads were blocked … Yet more and more people made their way up to the center of the city by walking … They came from all around Istanbul. They came from all different backgrounds, different ideologies, different religions. They all gathered to prevent the demolition of something bigger than the park: The right to live as honorable citizens of this country … They gathered and continued sitting in the park. The riot police set fire to the demonstrators’ tents and attacked them with pressurized water, pepper and tear gas during a night raid. Two young people were run over by the vehicles and were killed. Another young woman … was hit in the head by one of the incoming tear gas canisters. The police were shooting them straight into the crowd.”

The first North American article I read on the story was “How Democratic Is Turkey? …Â Not as democratic as Washington thinks it is,” published on the Foreign Policy website on June 3, 2013. Since then the plot has thickened – several times and in various directions. The question now is how much thicker can it get? (And personally, I can’t help asking, how much sadder will I be when it is all over, for the time being at least?)

Istanbul then and now … a miniature photo gallery

I did what tourists do in Istanbul, in late September 2007. I took photographs – in an especially intense and urgent state of mind, I think now, because there were so many interesting things to photograph. And the downtown street scene seemed very urbane, and open and inviting.

If you were religious when the call to prayer came, as it did a few times while I was walking around, you could go to prayers at a nearby mosque. If you were not religious, you could just keep sipping your coffee, or doing whatever else you were doing.

People were friendly. Many among those I bumped into spoke English (at least a lot better than I spoke Turkish). If you used euros, you would get change in Turkish currency, but you could use euros. And it quickly seemed to me you could take any photograph you wanted.

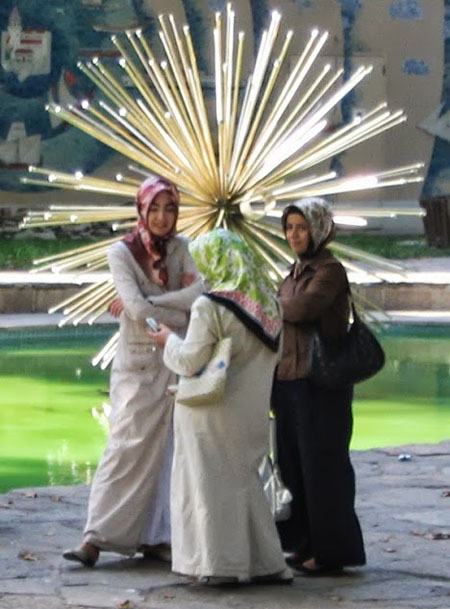

Fareed Zakaria has written that in the late spring of 2013 the “people protesting in Taksim Square are urban, middle class, secular. Notice that none of the women protestors wear headscarves.” Some six years before, I noticed more than a few women in beautiful downtown Istanbul (aka Sultanamet) who were not wearing headscarves (or, some might say, much of anything else either).

Yet there were also many women who did wear headscarves – and clothing that covered their entire bodies, from head to foot. But this clothing was not black or dark blue, as can even be sometimes seen nowadays on the streets of such North American places as Mississauga, Ontario. It came in bright and even (almost) sexually provocative colours. And the women wearing it had a lot to say – at least to each other – on the streets of Istanbul.

I think what I liked most about the city was the mood I picked up as I walked around. Words finally fail at such assignments. But, stabbing in the air somewhat blindly, the mood of Istanbul in the early fall of 2007 seemed to me about some kind of increasingly successful blending of various opposite or at least different things. As simple as old and new, as complex as tradition and modernity, stability and innovation, religious security and secular liberation, east and west (of course : blending east and west is what Byzantium/Constantinople/Istanbul has always been about, for more than 2500 years; or at least that’s what I think when I try to think about it now).

From another angle, the mood of Istanbul in the early fall of 2007 that I felt (on a single sunny day of walking around, to clarify how foolish my feelings may have been) was upbeat. The city seemed to be a place that knew it had many layers of a fascinating past, but that was also starting to think it could see new layers of an interesting future too. The global village, it seemed to be saying, is changing in altogether new ways, and nothing will ever be quite the same again. Istanbul – and even all of Turkey (based on another day in and around Izmir) is/was at a point where several key currents of the change intersected. It was beginning to understand how to navigate this intersection. And it probably had things to tell the rest of us about all this as well.

As already alluded to, I came away, in any event, with enchanted-tourist memories. When I look at the photographs I took then I seem to recover at least something of the original enchantment. (No one else may feel that way looking at some of the photographs here, but I cannot be blamed for that!)Â When I look at the most recent photographs of the city, not quite six years later, from the local, regional, and international media in the late spring of 2013, far too much of my earlier enchantment seems to vanish. It gives way to more troubling feelings about not just Turkey, but even the North America where I live myself today.

The future of Islamic democracy … and the Islamic republic

According to Adam Shatz, Iran today is “the world’s first and only Islamic republic.” And in some very exacting sense of ultimate theocratic rule by Muslim clerics, this is no doubt true enough.

But Pakistan, eg, began calling itself the Islamic Republic of Pakistan as long ago as 1956. (Canadians, and Australians etc, will be intrigued to remember that before that, Pakistan was known as the Dominion of Pakistan, from 1947 to 1956Â – having lasted considerably longer than its partner of sorts the Dominion of India, which officially gave way to the ostensibly quite secular Republic of India in 1950.)

Similarly, the modern Turkey that Kemal Atatürk established in 1923 was a republic (and the successor of the old Ottoman Sultanate). But, although the great majority of its people were Muslims, it was aggressively secular (as well as somewhat proto-fascist or perhaps crypto-fascist or quasi-fascist), rather than politically Islamic. And it did not even start to try to become democratic in any serious way until after 1945.

Over the past decade, however, under Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi in Turkish or AKP) , Turkey has seemed to qualify as both a kind of new model Islamic republic and an Islamic democracy. In its brightest light, it has even posed as a new model Islamic democratic republic, in blissful contrast to the example of Iran. It could be (or so the story goes) a template for aspiring Islamic democratic republics in such places as Egypt, Iraq, and virtually the entire Middle East and beyond.

The most troubling interpretation of the events that began during the last week of May 2013 in Istanbul’s Gezi Park is that they sadly mark the unhappy end of any and all illusions of this sort. So you hear : “How Democratic Is Turkey? …Â Not as democratic as Washington thinks it is.” And you wonder : is this the end of the Erdogan regime as any kind of model Islamic democratic republic for any relevant part of the global village? Again, I have no idea myself. I just do not know at all enough about Turkey. That having been said, as of this exact moment, I am not entirely persuaded that the situation is quite this grim. But who knows? It may be.

At the same time, some of the intelligence reported in the North American media over the past few weeks has also made me wonder whether some of the political things that are going on in Turkey right now are in fact strangely similar to some of the political things that are going on in my own North American backyard..

I go back to Fareed Zakaria’s posting on the CNN wesbite this past Friday: “Erdogan’s people, tend to be more conservative, religious, from places like Anatolia in the countryside. The people protesting in Taksim Square are urban, middle class, secular. Notice that none of the women protestors wear headscarves … If you’re looking for historical parallels, think of the images of the democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. There, too, you had an elected government that believed it had a mandate to maintain order but protestors on the street who were deeply frustrated and angry. And there, too, there was a culture gap — between the college educated protestors and the blue-collar cops who were policing the streets.”

My first thought after I read this was that you don’t have to go back to Chicago in 1968 for parallels in North America. The clash between more conservative, religious voters in the countryside (and the exurbs and suburbs) and the urban secular middle class – or what has elsewhere been described as the “conservative religious heartland largely backing Erdogan while Western-facing liberals swell the ranks of the protesters” – has at least broad analogues much closer to home. (As just one case in point, the much-criticized authoritarian style of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan may strike some Canadians as vaguely reminiscent of the bullying model of democracy sometimes associated with Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who is also no friend of the aggressive liberal secularists in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver.)

Erdogan himself has been taking pains to stress, with his own recent mass rallies, that he still does have his own quite impressive democratic support – and an up-to-now impressive track record in government.

So a political scientist specializing in Turkish government and currently residing in Spain explained this past Thursday : “The now decade-long AKParti rule has in many ways been a success. Turkey witnessed a decade of economic growth and stability, and since 2007 has continued to grow despite the global economic recession. Initial efforts to relax restrictions on religious expression were met with support not only from religious conservatives, but also from a subset of liberals and intellectuals who saw these policies as promoting civil rights. As well, the provision of basic services has improved, especially in rural and working-class urban districts. Citizens who have benefited from these developments, many of whom are more religious than their urban middle- and upper-class counterparts, consistently support the AKParti, whose vote share increased from 34% in 2002, to 47% in 2007, to 50% in 2011.” (Parliamentary democratic Canadians will not have trouble understanding that even with its only 34% first popular vote victory, the AKP has always had solid majorities of seats in the Turkish parliament, as a result of the country’s multi-party system – even though it actually only won just under 50% of the popular vote, even most recently, in 2011.)

Even so, the protestors do seem to be showing that there are more than a few things lacking in Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s model of an Islamic democratic republic. And, for the moment at any rate, he seems to be showing that, in spite of all his other achievements, he may not be the man to fix the model. The various current weaknesses and failures of our own regional models of democracy in various parts of the so-called West may help set the struggles in Turkey today in some kind of more benign perspective. And such altogether up-to-date headlines from today as “Poll shows rising support for Turkish opposition amid protests” may still hold out some optimistic prospects. But such other headlines as “Turkey could deploy army to quell protests” make me think that the enchanted-tourist mood I found on the streets of Istanbul in the early fall of 2007 (just a few months after the Erdogan AKP’s second big electoral victory, I now realize) is probably not going to return any time soon.

(Oh and btw, Business Week has recently reported that “Turkey is one of the top 10 tourist destinations in the world, attracting more than 31.78 million visitors in 2012, up 1.04 percent from the previous year … In April, the number of foreigners in Turkey jumped 13.02 percent year on year, the last month that data were available.” Not surprisingly, however, according to Kaya Demirer, president of Turyid, a Turkish restaurant and entertainment association, over the first week of June this year “hotels have seen a 30 percent cancellation rate and restaurants are empty.” Moreover, “Bloomberg News reports that retail sales in Istanbul’s Beyoglu area, which includes Taksim Square, have dropped as much as 80 percent in the past week … ’Will this have a long-term effect? If it continues to be a chaotic situation in Istanbul there’s no way it won’t,’ Demirer says, ‘When you lose one year, it takes three or four years to recover.’” So … stay tuned. The news from the old heartland of the Ottoman empire far away seems bound to be interesting, for a while yet.)