Turkey, Brazil, Rosa Luxemburg, and Hannah Arendt (and us too) .. participatory democracy returns?

Jun 25th, 2013 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

Turkish prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who said a conspiracy was behind recent protests in Turkey and Brazil. Photograph: Adem Altan/AFP/Getty Images.

[UPDATE JUNE 27 : On Margarethe von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt movie … scroll to bottom of page]. Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is not the only global political observer who has suggested similarities between the mass protests faced by his democratic government lately and those faced by the democratic government of President Dilma Roussef in Brazil.

See, eg : “Turkish PM likens the ongoing protest wave in Turkey to Brazil demonstrations” ; “Erdogan: le Brésil «victime d’un complot orchestré par des forces étrangères»” ; “Brazil and Turkey experience growing pains” ; “Parallel Protests in Turkey and Brazil” ; “Brazil And Turkey Rocked By Protests” ; and “Brazil and Turkey: Mass Demonstrations and anti-Government Feelings are Running High.”

The former CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar has even noted : “No doubt there is also a lot of sociology to be explored on the protesters’ end. Dissertations probably can be written that can explain some of what we are seeing in terms of generational change, evolving class structures, or the like … The same question about why a democratically elected government should be the target of action in the street can be applied to the United States as well as to Brazil and Turkey.”

While trying to ponder all this in a suitably modest way, I suddenly remembered the dwindling supply of used bookstores in the (northern) North American city where I reside. I also remembered how, a few weeks ago in one such place, I discovered J.P. Nettl’s “classic biography of one of the most important and controversial revolutionary leaders of twentieth-century Europe,” Rosa Luxemburg. And this has finally at least helped me dimly understand one thing about Turkey, Brazil, and all the rest of us who live in democracies today.

1. J.P. Nettl, Rosa Luxemburg, and Hannah Arendt

Nettl’s biography of Rosa Luxemburg first appeared in 1966, in two volumes. I actually read both volumes, borrowed from my undergraduate university library, as grist for an essay in a fourth-year course coyly called Political Theories of Social Change. It was one of the great experiences of my undergraduate education. Ever since I have been looking for a copy of Nettl’s classic biography to purchase, and place on the private bookshelves that insulate my aging soul from increasingly cold thoughts about what must ultimately lie ahead.

Nettl’s biography of Rosa Luxemburg first appeared in 1966, in two volumes. I actually read both volumes, borrowed from my undergraduate university library, as grist for an essay in a fourth-year course coyly called Political Theories of Social Change. It was one of the great experiences of my undergraduate education. Ever since I have been looking for a copy of Nettl’s classic biography to purchase, and place on the private bookshelves that insulate my aging soul from increasingly cold thoughts about what must ultimately lie ahead.

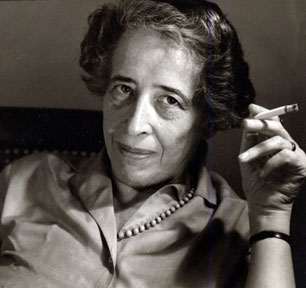

What I found recently in my neighbourhood bookstore was a one-volume abridgement of Nettl’s two volumes of 1966. It was published by Schocken Books in New York in 1989, based on an earlier one-volume edition published by Oxford University Press in 1969. The cover boasts the added attraction of “Introduction by Hannah Arendt” (the street-level German-Jewish émigré queen of a certain strand of New York intellectual life after the Second World War).

I thought to myself, well I won’t re-read the entire abridgement of Nettl’s two volumes just yet. (That can wait for some serious cold weeks in winter, when I am hopefully still older than I am now.) But I will read the introduction by Hannah Arendt. I finished it just when I started thinking about the current events of late spring and early summer 2013 in Turkey and Brazil.

As a sign of just how old I am, when I looked on the front pages of my new Schocken Books edition for the date of Arendt’s introduction, I discovered that it was republished from her book Men in Dark Times. And I soon enough remembered that I already have that book.

And then when I looked up Hannah Arendt’s essay on Rosa Luxemburg in my copy of Men in Dark Times, I saw it was almost freshly marked up in pencil. I vaguely remembered that I had looked at it again when I read Tony Judt’s re-assessment of Hannah Arendt a few years ago. One of the great joys of getting old is how you can barely remember books you’ve read and movies you’ve seen earlier – almost to the point where they are as fresh and stimulating as they were when you first encountered them

It finally became clear to me that Arendt’s piece on Rosa Luxemburg originally appeared as a review of J.P. Nettl’s classic two-volume biography in the October 6, 1966 issue of the New York Review of Books. My excuse for all this background is that I have decided Hannah Arendt’s writing on Rosa Luxemburg in the mid 1960s adds up to at least a potential provocative beginning for former CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar’s kind of “a lot of sociology to be explored on the protesters’ end” in Turkey and Brazil, in 2013.

Turkish police use water cannons to break up thousands gathered in Istanbul's Taksim Square. (Photo: Petr David Josek/AP).

In fact, what you get in both these brilliant ladies’ analyses is political theory or political thought, not “sociology.” But personally I think that is even more useful. It points to what Arendt said at the very end of her October 1966 review of Peter Nettl’s book on Rosa Luxemburg: “one would like to hope” that Luxemburg “will finally find her place in the education of political scientists in the countries of the West.”

This points as well to one of the great political science enthusiasms of the 1960s in which I grew up – “political participation” or “participatory democracy.” People like me would like to think that this enthusiasm has now found new enthusiasts, in such places as Turkey and Brazil. And who knows? That may even be at least half true?

2. Rosa Luxemburg and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in the early 20th century

Barbara Sukowa as Rosa Luxemburg in Margarethe von Trotta’s 1986 movie about Luxemburg, with her lover Leo Jogiches, played by the actor Daniel Olbrychski.

Rosa Luxemburg was certainly a person whom Joseph McCarthy would have called a communist (and with some justification). She was born in Poland in 1871 to an at least intermittently prosperous middle-class family. (Her father was a “timber trader.”)

As explained by her current Wikipedia article, she went on to become a “philosopher, economist and revolutionary socialist of Polish Jewish descent who became a naturalized German citizen. She was successively a member of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD), and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).” Following the ill-fated Spartacist uprising in Germany early in 1919, she was murdered by a right-wing paramilitary group.

It says something about Rosa Luxemburg’s distinctive political philosophy that interest in her work revived during the participatory democracy enthusiasm of the late 1960s and early 1970s – in Europe, North America, and some parts of the global village beyond. She was a confirmed revolutionary socialist, but she also believed passionately in democracy and popular participation in politics – and what Nettl calls “the clearly expressed support of a majority of the people.”

This put her in conflict with what might be called the revolutionary socialist elitism of the Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870—1924), who led the establishment of the Soviet Union in Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution of late 1917. And this sets the stage for the mid-1960s account of Rosa Luxemburg’s legacy by Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), that seems to me so interesting for what appears to be happening in Turkey and Brazil, in the late spring and early summer of 2013.

As Arendt explains the crucial disagreements between Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin never forgot the 1905 prelude to the later Russian Revolution, helped along in part by Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904—1905.

From this 1905 prelude Lenin “drew two conclusions. First, one did not need a large organization; a small, tightly organized group with a leader who knew what he wanted was enough to pick up the power once the authority of the old regime had been swept away. Large revolutionary organizations were only a nuisance. And, second, since revolutions were not ‘made’ but were the result of circumstances beyond anybody’s power, wars were welcome.

Demonstrators shout slogans during a protest in central Rio de Janeiro June 24, 2013. Credit: REUTERS/Lucas Landau.

“The second point was the source of her [ie Rosa Luxemburg’s] disagreements with Lenin during the First World War ; the first of her criticism of Lenin’s tactics in the Russian Revolution … with respect to the issue of organization, she did not believe in a victory in which the people at large had no part and no voice … she [as Nettl apparently puts it, Arendt notes in her review of his book] ‘was far more afraid of a deformed revolution than an unsuccessful one’ – this was, in fact, ‘the major difference between her’ and the Bolsheviks.

“And haven’t events proved her right? [Arendt goes on to write, and remember she is writing here in 1966]. Isn’t the history of the Soviet Union one long demonstration of the frightful dangers of ‘deformed revolutions’? Hasn’t the ‘moral collapse’ which she foresaw – without, of course, foreseeing the open criminality of Lenin’s successor – done more harm to the cause of revolution as she understood it than ‘any and every political defeat …’ could possibly have done? Wasn’t it true that Lenin was ‘completely mistaken’ in the means he employed, that the only way to salvation was [and the quotations here seem to be Luxemburg’s own words] the ‘school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the broadest democracy and public opinion,’ and that terror ‘demoralized’ everybody and destroyed everything?”

3. Turkey, Brazil, and the rest of us today …

Poster for UK conference on Rosa Luxemburg last year : “A towering figure of the twentieth century, Rosa Luxemburg has become an icon for those fighting for freedom and equality around the world.”

Turkey and Brazil are not countries which figured to any great extent in the political thinking of either Rosa Luxemburg or Hannah Arendt. That such places are more important today is a measure of one kind of progress in the wider global village since as recently the mid 1970s, when Arendt passed away all too early (just a little older than I am now!).

I would similarly argue that it makes sense to use Hannah Arendt’s mid-1960s account of Rosa Luxemburg’s conflict with Lenin as some kind of partial springboard in trying to understand the democratic protests of 2013 in Turkey and Brazil.

You can say that Rosa Luxemburg was a revolutionary socialist and even a “communist” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And this is no longer relevant in the early 21st century. But Hannah Arendt was no kind of communist (or even socialist) at all. What she admired in Luxemburg’s life and work was the passionate commitment to the “school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the broadest democracy and public opinion” – and what Peter Nettl describes early on in his book as Rosa Luxemburg’s “frequent use of the words ‘masses’, ‘majority’, and ‘democracy’.”

(There may also be some continuing relevance in the economist Rosa Luxemburg’s book of 1913 on The Accumulation of Capital. But that is beyond the purposes and beside the point of my hasty discussion here of political events a century later, in 2013.)

Demonstrators gather during a protest as police officers stand guard in central Rio de Janeiro June 24, 2013. Credit: REUTERS/Lucas Landau.

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan would, by all accounts, argue that his government is itself very democratic, since it won a majority of the popular vote in the Turkish election of 2011. Yet, strictly speaking, even in 2011 (to say nothing of 2007 and 2002)Â Â Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (or Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi, abbreviated AKP in Turkish) did not quite win a majority of the vote. It received what is variously reported as 49.9 or even 49.8%. The democratic majority, in the sense of 50% plus one, actually voted against Erdogan.

Moreover, according to the Gallup organization this past June 14: “With protests in Turkey continuing for nearly two weeks, Gallup data reveal trends in residents’ opinions that could be the undercurrents of the recent unrest. The most telling of these trends is Turks’ growing dissatisfaction with their country’s leadership — particularly among those living in Istanbul. The percentage of Turks living in Istanbul who approve of the job performance of their country’s leadership fell to 30% in 2012, from 59% in 2011. Among those living elsewhere in the country, leadership approval declined to 48% in 2012, from 57% in 2011.”

Still more importantly, it seems clear enough that Prime Minister Erdogan’s “conservative democracy” has almost no patience with the “school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the broadest democracy and public opinion,” among the protesters on Taksim Square in Istanbul.

Still more importantly, it seems clear enough that Prime Minister Erdogan’s “conservative democracy” has almost no patience with the “school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the broadest democracy and public opinion,” among the protesters on Taksim Square in Istanbul.

President Dilma Roussef in Brazil seems somewhat more sensitive to the popular or participatory democracy between elections being practised by the protesters against her government. (See, eg : “Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff promises major reforms … has proposed a referendum on political reforms in an effort to tackle protests that have swept the country.”) But there is a more than plausible argument that, even in democracies, even governments which claim to speak for the mass of the people have some almost natural tendency to gravitate towards the kind of elitism enshrined in Vladimir Ilyich Lenin’s “democratic centralist” model of political development.

In some similar context I want to quickly take up former CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar’s point that the “same question about why a democratically elected government should be the target of action in the street can be applied to the United States as well as to Brazil and Turkey.” And here it is no accident that one of the leading texts of the late 1960s participatory democracy movement in America was Peter Bachrach’s The Theory of Democratic Elitism: A Critique (first published in 1967, republished in 1980, and according to Bachrach himself, somewhat more accepted even by mainstream American political science by 1988).

To make a long story very short, the continuing power of the culture of democratic elitism in American government today, some would say, is reflected even in the already troubled second term of the presidency of the former Chicago community organizer Barack Obama. And the unapologetically elitist democracy of Stephen Harper, whose new Conservative Party of Canada was opposed by more than 60% of the electorate in his most recent election of 2011, is a still more obvious and undeniable case in point.

To make a long story very short, the continuing power of the culture of democratic elitism in American government today, some would say, is reflected even in the already troubled second term of the presidency of the former Chicago community organizer Barack Obama. And the unapologetically elitist democracy of Stephen Harper, whose new Conservative Party of Canada was opposed by more than 60% of the electorate in his most recent election of 2011, is a still more obvious and undeniable case in point.

Put another way, as Pierre Trudeau’s hero Lord Acton urged long ago, “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” And Rosa Luxemburg’s passionate commitment to the “school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the broadest democracy and public opinion” is the great antidote to this tendency in what her fellow German-Jewish émigré in the USA, Franz Neumann, called the democratic as opposed to the authoritarian state.

It may just be that Turkey and Brazil are very lucky to have some ardent practitioners of the antidote among their new democratic citizenries. And what we need in such older democracies as the United States and Canada is more of this kind of thing ourselves!

4. Appendix : Margarethe von Trotta’s movies on Rosa Luxemburg and Hannah Arendt

One of the many great attractions of internet research (along with risks that bear much watching, of course) is how investigating one branch of a subject can quickly lead you into intriguing sidebars on other closely related branches, about which you knew absolutely nothing before.

I end these far too long casual notes with two cases in point. As I knew nothing of until yesterday, the German director Margarethe von Trotta has made movies about both Rosa Luxemburg (1986) and Hannah Arendt (2012). In both cases the exemplary German actress Barbara Sukowa has played the lead role.

Something else I only discovered even more recently is that von Trotta’s movie on Hannah Arendt is actually being shown at this very moment in in the (northern) North American city where I reside. As of right now I believe I will have an opportunity to see this movie tomorrow. And if I do, I will briefly report back to this space on my reactions.

Meanwhile, anyone who has actually made it this far in this long-winded perambulation might also actually be interested in a video called “Filming Rosa Luxemburg and Hannah Arendt … from Hannah Arendt Center [at Bard College, in the Hudson valley of New York State] …Â A Panel discussion with Margarethe von Trotta, Pamela Katz, Leon Botstein, Norman Manea, and Roger Berkowitz … Saturday, Dec. 5, 2009.” You can watch (or at least listen to) this discussion online (the talking-head photography is rather blurry, but the sound is fine). It goes on for over an hour, I believe. I made it through the first 45 minutes or so myself, before feeling the call of more urgent tasks. It gives some vaguely more intimate sense of at least the present-day New York City/German high-culture survivals of the worlds of both Rosa Luxemburg and Hannah Arendt – two quite remarkable ladies who really did believe in democracy (in a way that, certainly I think, is still worth our considerable further attention today).

UPDATE JUNE 27, 1:30 AM : ON HANNAH ARENDT THE MOVIE. I read three reviews of this movie before seeing it : by Jason Anderson, Rick Groen, and Katherine Monk. I think I enjoyed Margarethe von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt more than any of these reviewers seem to have, with the possible exception of Jason Anderson.

Anderson does rate the thing 7 out of 10. I’d probably go for 7.5 or conceivably even 8, though certainly no higher than 8. I also like his capsule description : “A stately film about Hannah Arendt’s controversial reporting on the trial of Nazi official Adolf Eichmann in 1961.”

Walking out of the theatre, I wanted to reacquaint myself with Tony Judt’s reassessment of Arendt. This first appeared in the New York Review of Books in 1995, and was subsequently republished in his Reappraisals : Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century (2008). In Judt’s language von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt focuses on “the otherwise absurd furor over [Arendt’s 1963 book on] Eichmann in Jerusalem.”

Margarethe von Trotta’s movie also very much takes to heart this sentence from the second paragraph of Tony Judt’s 1995 piece : “Hannah Arendt was throughout her adult life concerned above all with two closely related issues: the problem of political evil in the twentieth century and the dilemma of the Jew in the contemporary world.”

From this angle, the movie is very much on the money. While I enjoyed the movie myself, however, it does not deal in any depth with the Hannah Arendt who most interests me.

I have never read Eichmann in Jerusalem (though I have certainly read about it). I own three other books by Hannah Arendt : The Origins of Totalitarianism (the book that made her reputation, first published in 1951) ; Men in Dark Times (essays on the European world that made her the person she was, 1968) ; and Crises of the Republic (essays on the democracy in America that nourished her life after the Second World War, first published in 1972, and dedicated to “Mary McCarthy in Friendship” – who figures quite prominently in Margarethe von Trotta’s movie as well, as played by Janet McTeer).

If I were going to make a movie about Hannah Arendt myself, it would be the Hannah Arendt who was Mary McCarthy’s great friend, who passionately shared Rosa Luxemburg’s concern for  the “school of public life itself, the most unlimited, the broadest democracy and public opinion,” and who spent her last years worrying about the late 20th century fate of Alexis de Tocqueville’s democracy in America.

Yet I of course do not make movies. And I have no doubt that – if only one movie is going to be made about Hannah Arendt (and let’s face it, we are lucky to have even one such thing) – the movie that Margarethe von Trotta has made is the one it ought to be.

I have just two final offerings on this front (and even that is far too much). The first is that my enthusiasm for this movie clearly flows from my comparatively unusual deep interest in various aspects of its subject matter. We do not get many movies, eg, about New York intellectual life in the third quarter of the 20th century. And this is a subject that intrigues me. My wife, on the other hand, although quite clever, is more interested in baseball. She wondered whether she might be interested in seeing Margarethe von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt, and finally decided the answer was no. If she ever does get around to looking at what I have written here, she will likely feel quite certain that she made the right decision. And if your tastes are more like hers than mine, you will probably not like the movie very much either.

Finally, all the reviews I have read underline just how great a contribution the work of the exemplary German actress Barbara Sukowa in the title role makes to the success of von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt. I couldn’t agree more myself. At the same time, I would like to offer an honourable mention to the German actress Friederike Becht, who briefly plays the young Hannah Arendt in Germany – who was the “lover of Martin Heidegger, the noted philosopher concerned with language and art who had a brief encounter with the Third Reich.” The real Hannah Arendt was a quite complicated character, which is partly why she remains as interesting as she does remain, for whatever exact reasons.

The movie turns ideas into the best kind of entertainment. There is an undeniable nostalgic thrill in stepping into an era in New York when philosophers lived in apartments with Hudson River views, and smoking was permitted even in college lecture halls, especially if you are someone for whom the summit of early-’60s Manhattan magic is not Madison Avenue or Macdougal Street but Riverside Drive. But it would be a mistake to file this film with all the other rose-colored midcentury costume dramas.