“The High Art of the Low Countries” and “In Search of Science” : two BBC programs north of the Great Lakes

Jun 22nd, 2014 | By L. Frank Bunting | Category: In Brief

One of the most successful TVOntario programs for many years was Elwy Yost’s “Saturday Night At The Movies” – and it probably didn’t help we the modern people of Ontario to begin to understand ourselves either, except as consumers of cultural products manufactured elsewhere.

I was complaining not too long ago, to someone fortunately wiser than I am, about how TVOntario has not lived up to the promise of its creation in the early 1970s. To no small extent, I said, it had become (in my own less-than-systematic perception at any rate) just another vehicle for the North American dissemination of British television programming.

This is a noble objective of much traditional (Anglophone) Canadian communications policy, no doubt. Yet back in the early 1970s it seemed for a few brief moments of madness that what Wild Bill Davis established as the Ontario Educational Communications Authority might start helping we the modern people of Ontario begin to understand ourselves.

The problem was (and of course still is), my wiser interlocutor explained, that it is just a lot cheaper to buy ready-made and frequently excellent British programming for regional distribution, than it is to create new regional programming of your own. And for at least the past quarter century (or more) TVOntario, like so much else in what many still think of as the broader public sector, has seen less and less of its revenue come from government tax dollars.

Most recently, I also seem to have stumbled across not just one but two quite good personal reasons for applauding the particular selections of British television programming TVOntario is currently making available. As it happens, by at least half an accident I caught both programs this past Thursday night – and I travelled a kind of spontaneous seam from one to the other.

Most recently, I also seem to have stumbled across not just one but two quite good personal reasons for applauding the particular selections of British television programming TVOntario is currently making available. As it happens, by at least half an accident I caught both programs this past Thursday night – and I travelled a kind of spontaneous seam from one to the other.

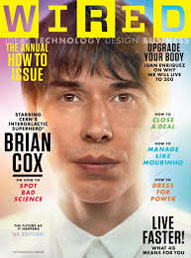

Both programs are parts of three-episode series originally produced for the BBC back across the North Atlantic. Last night I watched the last of the three episodes of The High Art of the Low Countries with Andrew Graham-Dixon. And then I watched the first of the three episodes of In Search of Science, where Professor Brian Cox “is going in search of the best of British science.”

This is of course not television programming for all tastes. But it is an attempt to blend educational and entertainment objectives in an engaging way.

There are similarly no doubt a variety of critical things one might say about the BBC in the early 21st century. Yet, thanks in part to the 2000 years of recorded history which still more or less weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living British public, the BBC and a certain strand of British television programming generally do seem to have figured out ways of doing programs like The High Art of the Low Countries and In Search of Science that work – certainly for people like me and probably you too.

There are similarly no doubt a variety of critical things one might say about the BBC in the early 21st century. Yet, thanks in part to the 2000 years of recorded history which still more or less weigh like a nightmare on the brain of the living British public, the BBC and a certain strand of British television programming generally do seem to have figured out ways of doing programs like The High Art of the Low Countries and In Search of Science that work – certainly for people like me and probably you too.

(Or you wouldn’t have made it even this far in this longish piece of instant digital text. And I do have a little more to say on each of the two BBC programs : click on “Read the rest of this page” and/or scroll below, if you must … and all that, old sport, or is that just what the Great Gatsby on Long Island would say?)

1. The High Art of the Low Countries – Andrew Graham-Dixon

To be altogether honest, I thought the third and final episode of Andrew Graham-Dixon’s High Art of the Low Countries, “Daydreams and Nightmares,” was the weakest of the series. The earlier two episodes – “Dream of Plenty” (1) and “Boom and Bust” (2) – struck me as considerably stronger.

Mr. Graham-Dixon himself almost seemed to be offering an explanation for this, at the end of the third episode. This dealt with the latest period in what are now the Netherlands and Belgium (and Luxembourg). And Graham-Dixon seems to believe that nowadays neither the Belgians (whoever they may be) nor the Dutch are really interested in great art, as they were in earlier eras, from the 16th on down to somewhere in the 19th century.

(I think I’ve got the dates more or less correct. But the 15th century may be a more exact beginning than the 16th. The BBC’s dates for Jan van Eyck, who did so much to pioneer oil painting, are c.1380—1390—1441.)

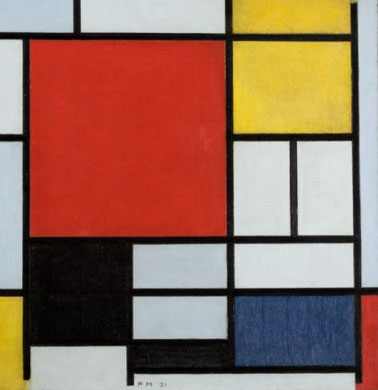

Without pretending to know anything serious about the subject, I think Graham-Dixon probably has a point – about how the Dutch have lost their passion for great art. The works of Pieter Bruegel (Brueghel) the Elder (c. 1525 —1569) certainly strike me as more interesting to look at than those of Pieter Cornelis “Piet” Mondrian (1872—1944) . Though I did think the Mondrian house Graham-Dixon introduced us to was intriguing – so long as I don’t have to live in it myself.

What most appealed to me in episodes 1 and 2 of High Art of the Low Countries – and is perhaps somewhat less on display in episode 3 – was how Andrew Graham-Dixon linked art history with political and economic history, in ways that freshly illuminate what are usually seen as very different subjects.

The high art of the Low Countries in its various heydays, that is to say, was a striking accompaniment to and even reflection of the birth of the European modern age around 1500, and its subsequent earlier history. The Low Countries were pioneers in the politics and economics of all this. And on certain still compelling views of how the world works, it is not surprising that the political and economic pioneering also gave birth to some great art.

Andrew Graham-Dixon’s approach more or less reverses the traditional Marxian assumptions about the direction of influence. He argues that studying the high art of the Low Countries, especially in the early modern era (and its late medieval prelude), is a compelling way of understanding the same era’s political and economic innovations.

These innovations came to a head in the so-called golden age, summarized well enough by today’s Wikipedia article on the Dutch city of Amsterdam: “The 17th century is considered Amsterdam’s Golden Age, during which it became the wealthiest city in the world. Ships sailed from Amsterdam to the Baltic Sea, North America, and Africa, as well as present-day Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, and Brazil, forming the basis of a worldwide trading network. Amsterdam’s merchants had the largest share in both the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company. These companies acquired overseas possessions that later became Dutch colonies … In 1602, the Amsterdam office of the Dutch East India Company became the world’s first stock exchange by trading in its own shares.”

The great political instrument of this economic expansion was the Dutch Republic, whose widest dates are 1581—1795. Graham-Dixon points alluringly in this direction with an optimistic painting by Peter Paul Rubens (28 June 1577 — 30 May 1640), at the end of episode one.

The Low Countries’ golden age and somewhat after is at the centre of episode two (which may be the best of all three?). The great artist of the Dutch Republic and the Golden Age is of course Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (15 July 1606 — 4 October 1669). And if all of the politics, economics, and high art of the Low Countries slipped into different and inevitably less brilliant phases in the 19th, 20th, and early 21st centuries, that is hardly Andrew Graham-Dixon’s fault.

2. In Search of Science with Professor Brian Cox

Brian Cox’s In Search of Science is a quite different kind of entertaining educational TV show than The High Art of the Low Countries. And since I have only seen the first of three episodes so far, I have mercifully less to say about it too (well … a little less, I think).

In some ways Cox’s show reminds me of a more elaborate BBC TV series from long ago in the 1970s, Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent of Man. Judging from the elegantly produced companion coffee-table book, a copy of which I still have, Bronowski’s show had some 13 episodes to tell its story, not just three. It was more about what science has contributed to the larger story of human beings on planet earth, and less about “Science” itself (to say nothing of the search for “the best of British science”). And it covered a longer time.

For the kind of broader general audience of which I am a member, however, both The Ascent of Man and In Search of Science are trying to bring vaguely interested non-scientists up to date on the current state of the art in science (well …). And the differences between Jacob Bronowski in the early 1970s and Brian Cox in the mid 2010s (?is that what it is now?) seem to say quite a lot about how a great many things have changed, over the past 40 years.

From Wikpedia you can learn that Brian Cox is a remarkable person from relatively ordinary circumstances. He was born in 1968 in the Manchester area of the UK, to parents who “were bankers.” He attended Hulme Grammar School in Oldham, and went on to study physics at the University of Manchester. He was also a rock-band keyboardist in his younger years. And midway through his physics education, “he joined D:Ream, a group that had several hits in the UK charts, including the number one, ‘Things Can Only Get Better’, later used as a New Labour election anthem.” Then : “After D:Ream disbanded in 1997, Cox completed his Doctor of Philosophy in high-energy particle physics at the University of Manchester.”

Nowadays, Brian Cox is “a member of the High Energy Physics group at the University of Manchester, and works on the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, near Geneva, Switzerland.” Yet he “is best known to the public as the presenter of a number of science programmes for the BBC, boosting the popularity of subjects such as astronomy and physics. He has been described as the natural successor for BBC’s scientific programming by both David Attenborough and the late Patrick Moore.”

To me, on the basis of just one hour’s TV acquaintance, Brian Cox looks and even sounds a little too much like the unbelievably juvenile Los Angeles physicists on the US TV situation comedy The Big Bang Theory . (And I’m not sure I even want to know what that means.)

I nonetheless started watching his three-part series In Search of Science this past Thursday night, only because it immediately followed the final episode of The High Art of the Low Countries. My initial thought was that I’d take a quick look and then move on. But I never did move on.

And now I intend to watch the next two episodes as well. So, as far as I’m concerned, Brian Cox is no Jacob Bronowski (whose book on The Ascent of Man was apparently reissued in the UK a few years ago, with a foreword by Richard Dawkins). But he does seem to be doing something right for the world as we know it today. And I’m intrigued to see if I can discover what it is!

If you can receive TVOntario where you live, the second episode of In Search of Science, “Frankenstein’s Monster,” will air Tuesday, June 24, 2014, 9 PM, and Thursday, June 26, 10 PM. The third episode, “Money,” will air Tuesday, July 1, 2014, 9 PM, and Thursday, July 3, 10 PM. A video of the first episode, “Method and Madness” is available online until July 17, 2014.

A video of the first episode of High Art of The Low Countries is available online until June 29, 2014. A video of the second episode is available until July 5, 2014, and of the third episode until July 19, 2014.

For a current example of the early 21st century high art spawned by the unique political and economic circumstances north of the Great Lakes in North America today (another “watery world,” as Andrew Graham-Dixon calls the European Low Countries), see “Michael Seward Visual Artist … ‘When I finish a painting, another piece of the puzzle falls into place for me’” ; and “The French fall classic 2006 .. and Central Europe in Toronto Art.”