Misty moment of contact : Giovanni Caboto and the British Monarchy (and Parliament) in Atlantic Canada, 1485–1689

Nov 19th, 2014 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage NowThis is Part I, Chapter 1 of Randall White’s work in progress, tentatively entitled Children of the Global Village : Democracy in Canada Since 1497. For more on the project see The Long Journey to a Canadian Republic, which also includes drafts of all remaining chapters in this initial prepublication format. The entire book in draft is now pre-published on this site. A final more carefully edited and source-referenced hard-copy print edition will be published by eastendbooks in the near future.

* * * *

One sign of the continuing influence of Harold Innis’s more than 90-year-old local classic, The Fur Trade in Canada, is that it remains in print today. And the first date it still points to in modern Canadian history is 1497.

Innis says nothing specific about the date. His first detailed reportage jumps to Jacques Cartier’s early exploration of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1534. He just seems to assume that his readers will already know about John Cabot’s brief encounter with today’s Atlantic Canada in the late spring or very early summer of 1497, on behalf of the English monarch Henry VII.

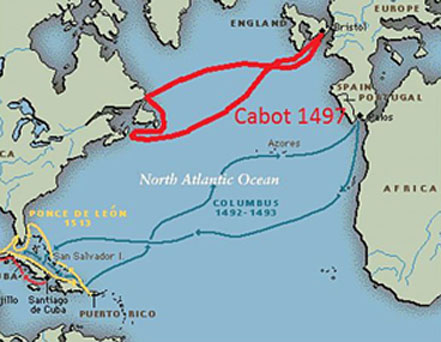

Cabot’s 1497 adventure — five years after Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to what we now know as America — can be understood from different angles.

Like Columbus’s voyage of 1492 , or Vasco da Gama’s arrival in India in 1498, it marks an early signpost on the long journey to what we now call globalization (or the world economy).

Somewhat more narrowly, Cabot’s voyage on behalf of Henry VII of England marks at least a formal beginning for English-speaking interest in North America. And this has significance for the modern histories of both Canada and the United States, and a number of islands in the present-day Commonwealth Caribbean.

More narrowly again, John Cabot’s voyage of 1497 inaugurates the history of the British monarchy in Canada. It would be more than a century before this history included any enduring English-speaking settlement. And this settlement started in Newfoundland, which did not finally join the modern Canadian political experiment until 1949. Yet it remains true enough that, in the late spring or very early summer of 1497 (as time is reckoned in the Christian or so-called Common tradition), a navigator commissioned by the King of England landed (probably) somewhere on the coast of what is now called Canada — of which the present British monarch, King Charles III, remains the symbolic ceremonial head of state (for the time being, at least).

* * * *

Whatever angle you come at John Cabot’s ocean-going voyage of 1497 from, there are qualifications which suggest good reasons for not jumping too quickly to any big conclusions about any aspect of anything involved.

Cabot himself, to start with, was not “English” (or “British”). He began life as Giovanni Caboto (aka Zuan Chabotto), born and raised in the political jungle of the 15th century Italian city states (also the home and native land of the Florentine bureaucrat Niccolo Machiavelli, 1469 –1527, arguably a key founder of modern political science in the global village).

Though he may have grown up in Genoa (like Columbus), Caboto ended the strictly Italian phase of his career as a citizen of the Republic of Venice. He was another forward-looking mercantile mariner who had begun to ponder the new truth that the earth was round, not flat. And he too thought that meant you could sail west from Europe directly to Asia.

He tried to interest the Spanish monarchy in certain further experiments. But Columbus already had that market cornered. So Caboto moved to England. There he managed to enlist the support of Henry VII and some merchants from the then enterprising western seaport of Bristol. And he reinvented himself as John Cabot.

Cabot may have understood that Christopher Columbus had not in fact reached the beginnings of Asia in 1492, as Columbus himself at first believed. He may have thought “that the western sea route to Asia remained to be discovered.” His way of differentiating his ultimate English project from Christopher Columbus’s Spanish voyage of 1492 also urged that, because the earth was a sphere, the westerly distance from Europe to Asia was shorter further north.

Derek Croxton, a young American historian writing in the late 20th century, memorably portrayed John Cabot’s ambitions: He “had a simple yet ingenious plan, to start from a northerly latitude where the longitudes are much closer together, and where, as a result, the voyage would be much shorter. Sailing west … he could reach land comparatively quickly, revictual, and coast southward until he found ‘Cipango’ or Japan.” And his “scheme might have succeeded were it not for Canada.”

* * * *

Surprisingly little is known from the surviving documents on Cabot’s voyage from Bristol to northern North America in the spring of 1497.

As explained on a website of the Newfoundland and Labrador provincial government today, Henry VII had “issued letters patent to Cabot and his sons authorizing them to sail to all parts ‘of the eastern, western and northern sea to discover and investigate ‘whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.’”

Cabot’s small but sturdy ship, the Matthew, with a crew of no more than 20 men (and perhaps less), reached some stretch of land on the North Atlantic coast of what Europeans would only later understand was, for them at any rate, a “new world” and not Asia at all. There seems some agreement nowadays that the land Cabot reached was probably in the present-day Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. But it may have been on Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, or even in the present US State of Maine.

Wherever Cabot landed, he did not stay long. He was unable to find fresh supplies and his crew grew nervous about running out. He undertook some further vague explorations and returned to Bristol. There his and his crew’s reports of their venture caused much excitement and won fresh support. A more elaborate five-ship voyage was launched in 1498. Its exact fate — and that of John Cabot himself — remains uncertain.

It seems to fit the case that the most interesting recent historian of Cabot’s “North American discovery voyages,” the late Dr. Alwyn Ruddock of the University of London, worked for years on what her peers expected would be a “groundbreaking volume,” that would resolve many longstanding mysteries of Cabot’s career, including his second voyage in 1498. But the book was never published. To thicken the plot, on Dr. Ruddock’s death “in December 2005, aged eighty-nine, she ordered the destruction of all her research.”

A seven-page book proposal for Dr. Ruddock’s groundbreaking volume which never appeared, along with subsequent correspondence, makes clear that she believed John Cabot finally returned to England “in the spring of 1500” and then died “less than four months after his return.” Her belief is reflected in Jasper Ridley’s late 1990s popular history of The Tudor Age, which proposes that John Cabot “died soon after his return to England.” And all this departs from the earlier view proposed by the controversial retired New England rear admiral and historian Samuel Eliot Morison, in his mid-1960s Oxford History of the American People. Morison believed that “We know nothing more” of John Cabot’s second voyage in 1498 “than that he started, but never returned; apparently the ships were lost with all hands.” In 2009 the University of Bristol in England established The Cabot Project, “to investigate the Bristol discovery voyages of the late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries — in particular, those undertaken by the Venetian adventurer, John Cabot … The origins of the project lie in Dr Evan Jones’ investigations of the research claims of Dr Alwyn Ruddock.”

* * * *

Regardless of exactly what happened in 1498, Giovanni Caboto’s voyage of 1497 on behalf of Henry VII still marks the beginning of the British monarchy and what subsequently became the British empire in Canada. Yet there are further qualifications which suggest good reasons for not jumping too quickly to any big conclusions about any aspect of anything involved.

To start with, properly speaking, there was no such thing as a British monarchy in 1497. At the very least that would have to wait until 1603, when King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England and Ireland — in the so-called union of the English and Scottish crowns.

Then some will want to stress that despite the union of the crowns in 1603, England and Scotland remained separate sovereign states, with separate parliaments or law-making bodies, until the Acts of Union in 1707 created the United Kingdom of Great Britain. And then again, finally, the British monarchy that some would say created the Canadian confederation of 1867, from which Canada today most recently descends, legally or institutionally, did not arrive until the Acts of Union of 1800 or 1801, which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

As some who grew up in English-speaking Canada during the 1950s may remember being taught with an ingenious folding-paper mechanism, this history is summarized symbolically in the evolution of the modern British Union Jack. It began with the English red cross of St. George on a white background — the flag flown by John Cabot on his voyage of 1497. This was first supplemented in the 17th century by the Scottish white diagonal cross of St. Andrew on a blue background, and finally completed in 1801 by the red diagonal cross of St. Patrick on white.

The independent Canadian maple leaf flag of 1965 had yet to be invented during the 1950s. The colonial Canadian red ensign which served in its place had a Union Jack in the top left-hand corner. This was accompanied by a shield in the centre right. It included three golden lions for England, a red lion rampant of Scotland, the Irish harp of Tara, three gold fleurs-de-lis of royal France, and a sprig of three maple leaves – green at first, finally turning red in 1957.

In the 20th century the historic golden-age incarnation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland also began to change again on its own home ground, with the gradual evolution of today’s Republic of Ireland in three stages (1922, 1937, and 1949). This has more recently been followed by the Scottish National Party, “devolution” and a separate Scottish Parliament, and the failed but influential referendum on Scottish independence in September 2014. There have been somewhat parallel developments in Wales and Northern Ireland. And even for the hallowed Union Jack there have been recent proposals “to incorporate black bordering around the crosses to represent the ethnic … diversity of the United Kingdom today.” (Though it also often seems that the still more recent UK “Brexit” adventure has been in part a protest against current British diversity. Which has nonetheless led to its own counter-protest against the protest, on behalf of more diverse white and non-white understandings of what it means to be “British” – if not exactly English, Irish, Scottish, or Welsh – in the 21st century.)

* * * *

There are still further complications in the history of the British monarchy outside and inside Canada since 1497 :

● Though his “claim to the throne was very dubious” (Jasper Ridley), Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond overthrew Richard III and made himself King of England as Henry VII in 1485.This marked the beginning of the end of the Wars of the Roses — a long bloody contest for the English crown between the House of Lancaster and the House of York.

● The Tudor monarchy to which Henry VII dubiously but effectively laid claim in the late summer of 1485 — and that would go on to include Henry VIII (who had six wives, two of whom were beheaded), Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey (the “nine day queen” who was finally beheaded), Mary I (“Bloody Mary” to some of her subjects), and Elizabeth I — had a lot in common with the political jungle of the 15th century Italian city states.

● During the 17th century England (and to some extent the Scotland involved in the 1603 union of the crowns) embarked on a period of political turbulence and experimentation, which finally culminated in the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688 – 1689. All this bequeathed the beginnings of a “constitutional monarchy,” whose powers were hedged by and shared with an increasingly influential Parliament.

● The high point of the age of turbulence and experimentation was the English Civil War between Parliament and the Crown (with something called the New Model Army more or less on Parliament’s side, from time to time). An inconclusive battle at Edgehill on October 23, 1642 began the conflict. It finally led to the execution of King Charles I on January 30, 1649, and the declaration of a republic known as the Commonwealth of England. Just before this, on January 4, 1649, the so-called Rump of the Long Parliament resolved that “the people are, under God, the original of all just power,” and that “the Commons of England in Parliament assembled, being chosen by and representing the people, have the supreme power in this nation.”

● At best the Commonwealth (or “English Republic,” as it is called in Winston Churchill’s History of the English Speaking Peoples) was premature. At worst (in the minds of some), it bred confusing early modern aspirations for democracy and almost a kind of communism. Even some confirmed English republicans (such as John Milton) realized they did not yet know just what to replace the executive power of the monarch with. All too soon the Commonwealth was replaced in 1653 by the Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell and then, briefly, under his son Richard.

● None of these arrangements proved durable. In a broader sweep of world history, they began a haphazard path towards the birth of the English-speaking American republic across the Atlantic Ocean, almost a century and a quarter later — presided over by an elected president instead of a hereditary monarch. But in England itself the monarchy was restored in the spring of 1660 under the son of the executed Charles I, Charles II, who had been in exile in France and what is now Belgium

● Charles II (the “Merry Monarch” of popular legend) was unusually clever and had the right personality to make the restoration work for a quarter of a century. Even he, however, fell out with Parliament in his later years. His brother James II, who succeeded him in1685, was an ideological Catholic in a country the Tudors had finally turned Protestant. James II was soon quarrelling mindlessly with Parliament. Then he began an aggressive policy of strengthening the position of his fellow Catholics in his Protestant kingdom. Then in June 1688 his queen bore him a son and heir.

● The English republic of 1649—1653 had not worked. But many of the social and economic forces behind it remained in play. Not long after the birth of James II’s son seven influential Englishmen (including the former Anglican Bishop of London and some prominent Whig aristocrats) invited the Dutch Protestant prince William of Orange (who, as luck would have it, was married to Mary, the daughter of James II) to invade England, and take over the monarchy.

● On November 5, 1688 William of Orange landed in England. Local supporters rallied to his side. By Christmas, he “was provisionally in charge of the government of England.” He “summoned a Convention Parliament, which met in February 1689.” William and Mary (again, James II’s daughter) “were accepted as joint sovereigns, and a Bill of Rights stated limitations on their power.”

● All this (again as well) was a 17th century homeland counterpoint to events on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, in what would eventually become the new United States of America. (And so the 1970 Ken Hughes’ movie Cromwell begins with the English legend in a moment of despondency, thinking that he too might soon move west to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.)

* * * *

There are two important final notes here for the history of democracy in Canada since 1497.

First, the practical political legacy that Canada today has, as it were, inherited from across the seas is what the Constitution Act, 1867 calls “a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.” And this is much more indebted to the ultimate Parliamentary victors of the Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689 than it is to any of the British monarchs who succeeded William and Mary. From the standpoint of how the government of Canada today actually works the historic and still highly valued if also congenitally reform-able gift from Westminster is parliamentary democracy — highest present-day heir of the Long Parliament’s 1649 assertion that “the people are, under God, the original of all just power.”

Second, and of much more immediate significance for this book, the British monarchy and the early British empire were, regardless of all other faults and even in some minds virtues or at least advantages, only minor misty actors in the deepest Canadian past from 1497 to 1763.

Some provocative mixtures of Indigenous, First Nations, or aboriginal peoples (or native North Americans) and other Europeans were much more important — and interesting from our vantage point today.

SOURCES

This is an initial dry-run at what will finally appear in a published hard-copy text, subject to further checking, correction, and editing. The order of the items here broadly matches the order of the text above. The online linkages reported are as of Summer 2023.

BC Historical Books Featured Collection, The fur trade in Canada : An introduction to Canadian economic history, Innis, Harold A. (Harold Adams), 1894-1952. An online accessible electronic copy of (an only somewhat battered but not at all impaired hard copy of) the 1930 original or first edition, published by Yale University Press. Compliments of the University of British Columbia.

https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcbooks/items/1.0374758

Harold A. Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. Introduction by Arthur Ray. EBOOK – EPUB, Published: June 2017 © 1999 (1970, 1962, 1956, 1930). University of Toronto Press, Series: The Canada 150 Collection.

https://utorontopress.com/9781487516840/the-fur-trade-in-canada/

amazon.ca, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History … Paperback — March 20 1999 … by Harold A. Innis (Author), Arthur Ray (Introduction), 4.3 out of 5 stars, 10 ratings … “At the time of its publication in 1930, The Fur Trade in Canada challenged and inspired scholars, historians, and economists. Now … Harold Innis’s fundamental reinterpretation of Canadian history continues to exert a magnetic influence.”

https://www.amazon.ca/Fur-Trade-Canada-Introduction-Canadian/dp/0802081967

Fur Trade in Canada [sound Recording] : an Introduction to Canadian Economic History … Harold A. Innis … University of Toronto Press, 1984 – Canada Economic conditions – 485 pages. [Scroll down for an interesting short bio on Innis that ultimately places far too much altogether unwarranted stress on a “Laurentian paradigm” that Innis himself never wrote about, and on Innis as someone with a Canadian “nationalist outlook” — which altogether misunderstands the author of both The Fur Trade in Canada, 1930 and Empire and Communications, 1950.]

https://books.google.ca/books/about/Fur_Trade_in_Canada_sound_Recording_an_I.html?id=7WJoPwAACAAJ&redir_esc=y

Memorial University of Newfoundland, A history of Newfoundland from the English, colonial, and foreign records. Prowse, D. W. (Daniel Woodley). London : Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1895, 1896. An online accessible electronic copy of a (tidy enough) hard copy of the early second edition of the Newfoundland judge Daniel Prowse’s classic history of what is now Canada’s youngest province, from 1485 to 1895.

https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/cns/id/26838

Newfoundland Historical Society [Terry Bishop-Stirling, James K. Hiller, Olaf U. Janzen, Peter E. Pope, Lisa Rankin, and Jeff A. Webb], A Short History of Newfoundland and Labrador. St. John’s, NL. : Boulder Publications [Boulder Books], 2008 [2013].

https://www.nlhistory.ca/publication/short-history/

https://www.amazon.ca/Short-History-Newfoundland-Labrador/dp/0978338189

Wikipedia, “John Cabot.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cabot

R.A. Skelton, “CABOT (Caboto), JOHN (Giovanni),” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume 1, 1966, 1979, 2014.

http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=34223

Derek Croxton, “The Cabot Dilemma: John Cabot’s 1497 Voyage & the Limits of Historiography,” Essays in History Published by the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, Volume Thirty-Three, 1990-1991.

http://etext.virginia.edu/journals/EH/EH33/croxto33.html

Fordham University, “Modern History Sourcebook: John Cabot (c.1450-1499): Voyage to North America, 1497.”

http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1497cabot-3docs.html

Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador, “John Cabot.”

https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/john-cabot.php

_________________, “John Cabot’s Voyage of 1497.”

https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/cabot-1497.php

Evan T. Jones, “Alwyn Ruddock: ‘John Cabot and the Discovery of America’,” Historical Research, Volume 81, Issue 212, May 2008, p. 224-254 … First published: 05 April 2007 … “Other documents she mentions revealed what happened to the 1498 expedition, the fate of which has never been established. She also claimed to have discovered evidence of a religious mission to Newfoundland in 1498, which resulted in the construction of the first church in North America.”

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1468-2281.2007.00422.x

Jasper Ridley, A Brief History of The Tudor Age. London : Constable, 1998, Constable & Robinson, 2002, 210-211.

Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People. New York : Oxford University Press, 1965, 29.

http://www.amazon.ca/The-Oxford-History-American-People/dp/0195000307

Wikipedia, “Samuel Eliot Morison … Morison was criticized by some African-American scholars for his treatment of American slavery in early editions of his book The Growth of the American Republic, which he co-wrote with Henry Steele Commager and later with Commager’s student William E. Leuchtenburg.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Eliot_Morison

Howard Zinn, “Columbus and the Lens of History,” howardzinn.org, nd … “One can lie outright about the past. Or one can omit facts which might lead to unacceptable conclusions. Morison does neither. He refuses to lie about Columbus. He does not omit the story of mass murder; indeed he describes it with the harshest word one can use: genocide … But he does something else—he mentions the truth quickly and goes on to other things more important to him.”

https://www.howardzinn.org/collection/columbus-lens-of-history/

Steve Sailer, “Samuel Eliot Morison And America’s Displaced Protestant Establishment,” vdare.com, 02/28/2010

https://vdare.com/articles/samuel-eliot-morison-and-america-s-displaced-protestant-establishment

University of Bristol, Department of History, “The Cabot Project.” https://www.bristol.ac.uk/history/research/cabot/

UK Parliament, “Union of the Crowns.”

https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/act-of-union-1707/overview/union-of-the-crowns/

__, “Act of Union 1707.”

https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/act-of-union-1707/

__, “An Act for the Union of Great Britain and Ireland.”

https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/parliamentandireland/collections/ireland/act-of-union-1800/

Wikipedia, “Coat of arms of Canada.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coat_of_arms_of_Canada

Scottish National Party/SNP, “Delivering progress for Scotland.”

http://www.snp.org/

BBC News, “Rebranding puts black marks against UK flag,” Wednesday, 11 June 2003, 11:06 GMT 12:06 UK.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/2981038.stm

George Clark, English History : A Survey. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1971, 183–335.

https://www.amazon.ca/English-History-George-Norman-Clark/dp/0198223390

Banqueting House, “The Execution of Charles I : Killing of a ‘Treasonous’ King … Charles was convicted of treason and executed on 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall.”

https://www.hrp.org.uk/banqueting-house/history-and-stories/the-execution-of-charles-i/#gs.1p34ee

‘House of Commons Journal Volume 6: 4 January 1649’, in Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 6, 1648-1651 (London, 1802), pp. 110-111. British History Online. [accessed 24 March 2023].

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/commons-jrnl/vol6/pp110-111.

Thomas Babington Macaulay, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second. Volume One. London : J.M. Dent & Co., 1848, 1906, 1909.

Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution (With an Introduction by R.H.S. Crossman). London : Collins — Fontana Library, 1867, 1915, 1963, 1964.

https://www.amazon.ca/English-Constitution-Introduction-R-Crossman/dp/B001COLLTM

F.W. Maitland, The Constitutional History of England. Cambridge University Press, 1908, 1974.

Ivor Jennings, Cabinet Government. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1936, 1969.

G.M. Trevelyan, The English Revolution 1688–1689. New York : Oxford

University Press, Galaxy Book, 1938, 1965.

Basil Williams, The Whig Supremacy 1714–1760. Oxford University Press, 1939, 1962, 1974.

Winston S. Churchill, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Volume Two : The New World. New York : Dodd, Mead & Co., 1956, 1959. Mr. Churchill’s chapter 19 of this volume begins with (p. 285) : “The English Republic had come into existence even before the execution of the King. On January 4, 1649, the handful of Members of the House of Commons who served the purposes of Cromwell and the Army resolved that ‘the people are, under God, the original of all just power … that the Commons of England in Parliament assembled , being chosen by and representing the people, have the supreme power in this nation’.”

Christopher Hill, “Oliver Cromwell 1658–1958,” Historical Association, Pamphlet Number 38, 1958, 1967.

________________, The Century of Revolution 1603–1714. London : Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1961, Sphere Books, 1969.

________________, Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution. London : Granada Publishing, 1965, 1972.

J.H. Plumb, The Growth of Political Stability in England 1675–1725. London : Macmillan, 1967, Peregrine, 1969.

Robert Beddard, A Kingdom without a King : The Journal of the Provisional Government in the Revolution of 1688. Oxford : Phaidon Press, 1988.

Adam Gopnik, “What Happens When You Kill Your King … After the English Revolution—and an island’s experiment with republicanism—a genuine restoration was never in the cards.” The New Yorker, April 17, 2023, April 24 & May 1, 2023 Issue. (A review of Jonathan Healey, The Blazing World, Knopf.)

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/04/24/the-blazing-world-jonathan-healey-book-review

Canada, Justice Laws Website, Constitution Act, 1867. 30 & 31 Victoria, c. 3 (U.K.). “Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom:”

https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-1.html

* * * *

Randall White has a PhD in political science from the University of Toronto. From the late 1960s to the early 1980s he worked as an Ontario public servant. He has subsequently worked as an independent public policy consultant for private and public sector clients at all three levels of government in Canada and the United States. He has written 11 books on history and politics, and is at work on a twelfth.

Mr. White has served on the Editorial Advisory Committee of the journal Ontario History. And he has published articles and reviews in such places as the Canadian Journal of Political Science, the Globe and Mail, Loonie Politics, Ontario News Watch, the Toronto Star, and Urban History Review. His current writing on Canada and beyond appears intermittently on counterweights.ca and birdhop.com.