Canada – peacemaker or powder monkey today .. and three 18th century wars that made two countries

May 16th, 2015 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In Brief

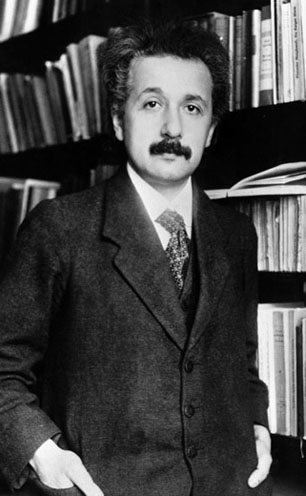

Freeman Dyson’s recent interesting note on Albert Einstein and the old  “dualistic philosophy” of quantum mechanics – masquerading as a New York review of Stephen Gimbel’s Einstein: His Space and Times – has also made some of us think about what ought to be another big issue in this year’s Canadian federal election. (Believe it or not!)

The abolition of nuclear weapons became one of the great causes of Einstein’s later life. One of his last acts before his death on April 18, 1955 (about five weeks after the much younger modern jazz giant Charlie Parker) was to sign a public statement underlining the unprecedented dangers of nuclear war, later known as the Russell—Einstein manifesto.

Dyson explains that : “After the Russell-Einstein manifesto was published, there grew out of it an organization called the Pugwash movement, bringing together scientists from East and West to discuss the problems of war and weapons. The name Pugwash came from the small town in eastern Canada where the first meeting was held in 1957. Since that time, meetings have been held in many countries, continuing up to the present day.”

Dyson’s review of  Einstein: His Space and Times has been passed around here at the office. It reminded a number of us of a book about Canadian foreign policy first published in 1960 by the then CBC Washington correspondent James M. Minifie, and very provocatively called Peacemaker or Powder-monkey: Canada’s Role in a Revolutionary World.

Dyson’s review of  Einstein: His Space and Times has been passed around here at the office. It reminded a number of us of a book about Canadian foreign policy first published in 1960 by the then CBC Washington correspondent James M. Minifie, and very provocatively called Peacemaker or Powder-monkey: Canada’s Role in a Revolutionary World.

With only a little more digging on the wonderful world wide web, we were not surprised to find a much more recent blog item by a disgruntled old federal progressive conservative from the Niagara region, with the equally provocative title today : “Canada in the Ukraine: Peacemaker or Powder Monkey?”

In several respects Mr. Minifie’s book was unusually successful back in the early 1960s. Still more importantly, no doubt, the accession of the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize winner Lester Pearson to the office of Prime Minister of Canada, in April 1963, locked in the emerging “peacekeeping” tradition in Canadian foreign policy after the Second World War.

Latest news is Natalie Portman will portray Jackie Kennedy in a new period drama about the days immediately after the assassination of JFK in 1963. JFK’s fellow liberal democrat Lester Pearson first became prime minister of Canada in the same year.

It may be that, even without Stephen Harper and his new Conservative Party of Canada, the powder-monkey side of James M. Minifie’s “dualistic philosophy” of Canadian foreign policy would have reasserted itself for a time in the early 21st century.

What we do know for the plain truth is that under the Harper government there has been a premeditated long march into powder-monkey territory. (We can never really be dangerous or militarily menacing in Canada, of course  – we are just nowhere near big enough, in every way except geographically.)

And we here aggressively agree with the rising proposition that, regardless of how we the people of Canada today have wound up in the powder-monkey’s pocket, it is time for some kind of vigorous return to the post Second World War peacemaker tradition. The past decade and a half has finally shown once again how peacekeeping is more useful and important work for a country like ours in the contemporary global village. And it is probably  more dangerous too.

We also ought to be hearing more about the peacemaker vs powder-monkey debate in Canadian foreign policy in this year’s federal election than we probably will. The old Latin tag  Si vis pacem, para bellum (“If you want peace, prepare for war”) still strikes many among us as ultimately compelling.  But it may well be as obsolete today as the Latin language itself. And “If you want peace, work for it” almost certainly makes more sense for countries like Canada, with only modest shares of the world’s demography and wealth, at best.

The now almost forgotten middle act of the three great (northern) North American wars of the 18th century, that bequeathed the essential broad political framework we still have today.

Meanwhile, all these thoughts of Canada and war have reminded us that  it is time for yet another installment of Randall White’s Children of the Global Village book project – on our Long Journey to a Canadian Republic page.

If you go to the page, on the bar at the top above (or just CLICK HERE), you will find a brief account of the project, along with the “Prologue : too much geography” – followed by links to Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Chapter 4, and Chapter 5 of PART I : THE DEEP CANADIAN PAST, 1497—1763.

You will now find as well a link to the concluding Chapter 6 of PART I : “Three 18th century wars that made two countries, 1754—1784.”

From a place  in the sun, nursing a small regular coffee on a park bench across the street from the nearest Tim Horton’s, Dr. White explained :

“Three successive bloody conflicts over a single generation, from the mid 1750s to the mid 1780s, established (somewhat ironically) the essential broad political framework for North America north of the Rio Grande that we are still living with today. This concluding chapter of Part I just tries to sketch what happened in a comparatively short space, and (necessarily in a history of Canada) from a present-day Canadian point of view.”