The new northern British America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

Jun 17th, 2015 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage NowOn the world wide web in the summer of 2015 the Wikipedia entry for “United Empire Loyalist” declared that “Loyalists settled in what was initially Quebec … and modern-day Ontario … and in Nova Scotia (including modern-day New Brunswick). Their arrival marked the beginning of a predominantly English-speaking population in the future Canada west and east of the Quebec border.” (Where Loyalists, again, were former residents of the new United States who remained loyal to the British Crown and the “United Empire”.)

This Wikipedia Loyalist account has evolved somewhat since 2015. Yet even in its mildly revised winter 2024 edition it still overlooked earlier migrations into what is now Atlantic Canada from the United Kingdom and what eventually became the United States (the slowly gathering resident fishermen of Newfoundland and John Bartlet Brebner’s Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia, eg), fur trade stragglers into what are now Ontario and Quebec from Albany and New York after the Peace of Paris in 1763, and the transient operators of Hudson’s Bay Company trading posts since 1670.

New Brunswick is properly enough known as “The Loyalist Province.” It was established in 1784 to accommodate comparatively large numbers of American Loyalists who had moved to what had been mainland Nova Scotia. But New Brunswick also became the largest ultimate refuge for French-speaking Acadians. Today it is probably best known beyond its own borders as Canada’s only “officially bilingual province.”

The Ontario provincial government adopted a Loyalist Latin motto in 1909 (Ut incepit fidelis, sic permanet or “Loyal she began, loyal she remains”) —125 years after the Loyalist migrations of the late 18th century. Yet the great majority of the English-speaking people who moved into the new Province of Upper Canada (the future Ontario) during the late 18th and early 19th centuries were ordinary frontier migrants from the United States, attracted by cheap land for pioneer family farms (and sometimes quaintly known as “late Loyalists”).

Similar northward continental migrations — spillovers from the same go-west frontier that would finally take the United States all the way to the Pacific Ocean — had brought the neutral Yankees to Nova Scotia. And American frontier migrants would later help spread the culture of the English-speaking peoples over “the last best west” in Western Canada.

In fact, British empire loyalism in the early history of English-speaking Canada had at least as much to do with an anglophile, conservative, elitist, and monarchist local political ideology, as with any real-world demographic history. Yet from the end of the American War of Independence all the way to the end of the Second World War (and even somewhat later), “Loyalist” ideology enjoyed a social and cultural weight in Canada that transcended its at best modest demographic dimensions.

To no small extent, this was because “United Empire Loyalism” did help buttress or explain a key existential fact of life for the ongoing evolution of a Canadian political and economic community, separate from the rising young giant of the new American Republic next door.

Whatever else (and even to the francophone majority in Quebec), the history of the 65 years after the Peace of Versailles in 1783 showed that, just as the fur trade and the cod fisheries “made inevitable the continuation of control by Great Britain in the northern half of North America,” the modern Canada that began in the 16th and 17th centuries could almost certainly not avoid being absorbed by the rising new United States in the 19th century, without the military, political, and even economic and cultural protection of the United Kingdom and the increasingly global British empire.

* * * *

The first stark demonstration of this fact of political life was the North American War of 1812. In the early 21st century plots to revive old colonial Canadian attachments to military royalism, the British monarchy, and even, it sometimes seemed, the fallen British empire, made (or re-made) what should more properly be called the North American War of 1812–14 an over-indulged object of partisan veneration.

The veneration ebbed when the partisanship changed in 2015. Yet another nagging sense that 1812–1814 has played a role of consequence in Canadian history predates the early 21st century. One of the major projects of late 20th century English-speaking Canada’s best-known (and quite liberal) popular historian, Pierre Berton, was a two-volume account of the War of 1812 published in 1980 and 1981, in the age of the first Quebec sovereignty referendum and the birth of the Constitution Act, 1982.

In some respects, this early 19th century war in North America just echoed all three wars of the mid to late 18th century. The chief combatants were the new United States and the old United Kingdom, and it was the former that declared war on the latter. The major grievance of the United States was the United Kingdom’s habit of impressing American sailors into the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars. The major enthusiasm of at least some states of the new union was the apparent prospect of painlessly acquiring Canada — or, as many stateside saw things, of liberating the new Province of Upper Canada from British imperial rule.

(Pierre Berton put the bold declaration Henry Clay from Kentucky made to the US Senate in February 1810 at the start of his book: “The conquest of Canada is in our power … the militia of Kentucky are alone competent to place Montreal and Upper Canada at your feet.” The controversial Samuel Eliot Morison in his American history quotes the Virginia Congressman John Randolph, who opposed the war, and “poured his scorn on this ‘cant of patriotism,’ this ‘agrarian cupidity,’ this chanting ‘like a whippoorwill, but one monotonous tone – Canada, Canada, Canada!’.”)

US forces did invade Upper Canada (what is now Ontario), and wreak some havoc. But they were finally pushed back onto their own side of the border. Unlike some of his predecessors (and successors), Pierre Berton was honest enough to point out that the successful defence of the province did not have much to do with its 75,000 or so only recently arrived English-speaking settlers — “most of them Americans” who “did not want to fight” and “certainly did not call themselves Canadian. (That word was reserved for their French-speaking neighbours, many of whom lived on American soil in the vicinity of Detroit.)”

North of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River, the real heroes of the War of 1812–14 were the regular troops of the British army and their Indigenous allies. Pierre Berton goes on to explain that the “role of the Indians and that of the British regulars was played down in the years following the war. For more than a century it was common cant that the diverse population of Upper Canada — immigrants, settlers, ex-Americans, Loyalists, Britons, Scots, and Irish — closed ranks to defeat the enemy. The belief still lingers, though there is little evidence to support it.”

Berton also allowed that, even though it was the British regulars and the Indigenous warriors who turned back the American invasion, “in an odd way … the myth of the war … encouraged and enforced by” a “pro-British ruling elite” helped give “rootless new settlers a sense of community.” In the very end both the “myth of the people’s war” and the might of the second British empire helped ensure that, unlike such places as the Mexican provinces of Texas or California a little further down the road (where restless American frontier migrants also settled), “Canada would not become a part of the Union to the south.” Instead, very gradually over the next century, “an alternative form of democracy grew out of the British colonial oligarchy in the northern half of the continent.”

* * * *

The Indian or Aboriginal or Indigenous side of the War of 1812 makes another largely forgotten part of it look like a reprise of Francis Parkman’s Conspiracy of Pontiac immediately after the Peace of Paris in 1763. The ultimate British effort to replace Onontio, and become a new father to Richard White’s Algonquians, was never entirely successful. But for a time it worked well enough.

There is even a serious sense in which the strategy that finally preserved Canada in the War of 1812–14 was an updated version of the strategy that Governor Vaudreuil had unsuccessfully urged on Montcalm in the late 1750s. Like Vaudreuil, by 1812 the new British colonial masters had at least come to appreciate the northern North American “necessity for the colony to maintain its native alliances.”

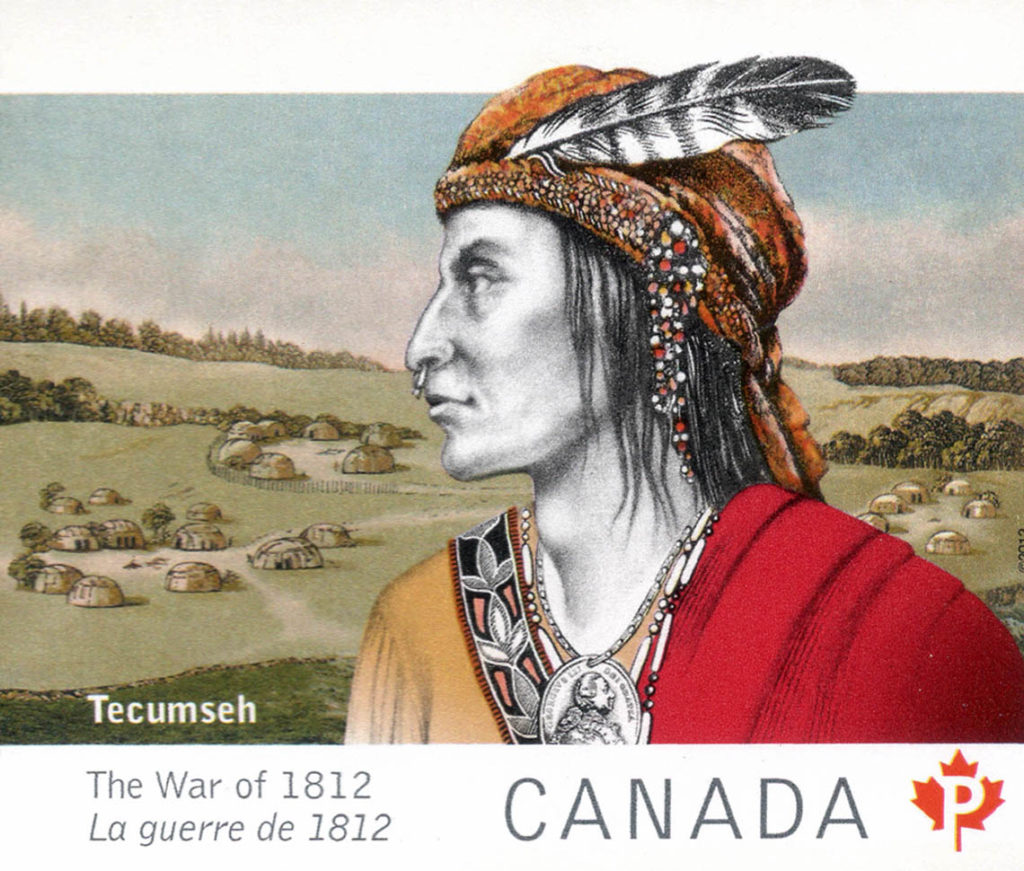

On the other side of the middle ground, the Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes who had once followed Pontiac were still fighting the never-ending assault on their ancestral lands by the restless Anglo-American settlement frontier, now with the unflinching force of the new United States of America behind it. This time the Shawnee Prophet had taken up the role of the old Delaware Prophet, and Pontiac himself was succeeded by Tecumseh — leader of a multi-tribal confederacy, that formally allied with the British empire in the War of 1812.

Unhappily, the war did not work out as well for Tecumseh and his confederacy as it did for Canada. (The American historian Alan Taylor, who sees the War of 1812 as a kind of “civil war,” has also urged that the ultimate settlement was “most ominous to the Indians.”) Tecumseh himself died at the Battle of the Thames River, near present-day Chatham, Ontario, on October 5, 1813. His confederacy had fought for the British father, in exchange for support of “a vision of establishing an independent American Indian nation east of the Mississippi.” When peace negotiations between the United States and the United Kingdom finally began, at Ghent in Belgium, during the summer of 1814, British negotiators actually translated this into (in the tidy words of Pierre Berton) : “Great Britain wants an Indian buffer state separating the United States from Canada, an area in which neither Canadians nor Americans can purchase land.”

But the United States would not even think about this demand. (Already some “hundred thousand white settlers … occupy the proposed Indian buffer state.”) And the United Kingdom had dropped it as a negotiating position by the fall of 1814.

In the lower Great Lakes and all points east the War of 1812 spelled the beginning of the end for the old Indigenous-European middle ground as well. According to Richard White: “It would be an exaggeration to say that the middle ground died in battle with Tecumseh … It died in bits and pieces, but with the death of Tecumseh, its attempt to rally failed. The imperial contest over the pays d’en haut ended with the War of 1812, and politically the consequence of Indians faded. They could no longer pose a major threat or be a major asset to an empire or a republic.”

North American native peoples would have a somewhat different fate in Canada than in the United States. They are referred to in Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982, but not in the American Constitution. There are Métis (or mixed race) peoples of Canada, but no such official category in the United States (as there is “mestizo” in Mexico). And then there is Harold Innis’s complaint of 1930: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.”

At the same time, Canada would have its own mass settlement frontier. And south and east of Lake Superior and Lake Huron, it began to grow rapidly enough after the War of 1812. In many ways Richard White’s concluding two sentences apply to both the United States and Canada: “Tecumseh’s death was a merciful one. He would not live to see the years of exile and the legacy of defeat and domination.”

* * * *

With a few brief exceptions, the War of 1812 was fought almost entirely in what is now Ontario — the old upper country west of Montreal, that had become the new British Province of Upper Canada in 1791.

The “two Canadas” of 1791—1841 (ie present-day Ontario and Quebec, or Upper and Lower Canada in the old British colonial lexicon that many today find amusing) did not include all the wider British North America under “the second empire.”

To start with, the British North American Atlantic provinces of Newfoundland (1610), Nova Scotia (1713), Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island, 1720), and New Brunswick (1784) were not part of “Canada” in the first half of the 19th century.

Neither were the vast spaces of the Rupert’s Land that Charles II had (again somewhat presumptuously, to say the least) assigned to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 — or the Pacific Coast region that is now British Columbia (visited in the late 18th century by sea by the Spanish commander Esteban José Marténez, and the British seafarers Captain Cook, John Meares, and George Vancouver, and then “from Canada by land” in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by the fur traders Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson).

The British Parliament’s Constitutional Act of 1791 divided the old Province of Quebec into two new provinces (as in the “two Canadas” or the more southerly parts of today’s Ontario and Quebec above). And this began the long process by which the more culturally specific and almost folkloric “Canada” of the 17th and earlier 18th centuries gradually expanded into the larger Canadian political community of today.

Yet, as Pierre Berton alluded to, even in the earlier 19th century a Canadian (or Canadien) was still someone who spoke French. By the 1830s it seems clear enough that there were a few English-speaking people west of the Ottawa River who had begun to think of themselves as Canadians. But this was only the beginning of a surprisingly long process — that had its first major broadening out with the 1867 confederation and that, in various ways, has continued into the early 21st century.

Throughout the 65 year-period from the end of the American War of Independence in 1783 to the achievement of so-called colonial “responsible” self-government in 1848, the most general name for the territory north of the new United States that is nowadays Canada was still just British North America. And — contrary thoughts among some Indigenous peoples notwithstanding — the ultimate sovereigns over this broad territory (much of the exact boundary of which remained quite uncertain) were the British monarchs George III (1760–1820), George IV (1820–1830), William IV (1830–1837), and Queen Victoria (who came to the throne as a young lady in 1837, and stayed there into a celebrated old age, until 1901).

The first British North America that the world began to recognize as the new United States of America in 1783 was succeeded by a new more northerly variation on the theme. Or (yet again) as Richard White has so poetically summarized the ultimate legacy of Pontiac, he “rose against the British to restore his French father and created a British father instead.” The War of 1812 marked the beginning of the end of the Indigenous-European middle ground. Yet something of Pontiac’s unique achievement would live on (and become a kind of hidden groundwork for the Canadian political confederation created in the wake of the American Civil War).

SOURCES

This is an initial dry-run at what will finally appear in a published hard-copy text, subject to further checking, correction, and editing. The order of the items here broadly matches the order of the text above. The online linkages reported are as of Winter (or 1Q)2024.

Wikipedia, “United Empire Loyalist.” … “These Loyalists settled in what was initially Quebec (including the Eastern Townships) and modern-day Ontario, where they received land grants of 200 acres (81 ha) per person, and in Nova Scotia (including modern-day New Brunswick). Their arrival marked the beginning of a predominantly English-speaking population in the future Canada west and east of the Quebec border.”[2015].

“American Loyalists who resettled in British North America during or after the American Revolution … settled primarily in Nova Scotia and the Province of Quebec … This resettlement added many English speakers to the Canadian population. It was the beginning of new waves of immigration that established a predominantly Anglo-Canadian population in the future Canada both west and east of the modern Quebec border.” [2024].

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Empire_Loyalist

Simner, Marvin L., “A Misguided Attempt to Populate Upper Canada with Loyalists After the American Revolution” (2023). History Publications. 413.

https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/historypub/413

https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1703&context=historypub

University of New Brunswick Libraries, “Black Loyalists in New Brunswick, 1783-1854.”

https://preserve.lib.unb.ca/wayback/20141205152154/http://atlanticportal.hil.unb.ca/acva/blackloyalists/en/

R. Cole Harris (ed), Geoffrey J. Matthews (cartographer/designer), Historical Atlas of Canada, Volume I, From the Beginning to 1800. Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 1987, 80.

https://www.amazon.ca/Historical-Atlas-Canada-Beginning-1800/dp/0802024955

https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDM157718&R=157718

—————————, Historical Atlas of Canada, Volume II, The Land Transformed, 1800–1891. Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 1993, 24–25.

https://www.amazon.ca/Historical-Atlas-Canada-Transformed-Addressing/dp/B008NN5F1K

Graeme Wynn, “On the Margins of Empire 1760–1840” in Craig Brown, ed., The Illustrated History of Canada. Toronto : Lester Publishing , 1987, 1991, 217–221. Montreal & Kingston : McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2012, 211–215.

https://www.mqup.ca/illustrated-history-of-canada–25th-anniversary-edition–the-products-9780773540897.php

John Bartlet Brebner, The neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia: a marginal colony during the revolutionary years. New York : Columbia University Press, 1937.

http://books.google.ca/books/about/The_neutral_Yankees_of_Nova_Scotia.html?id=QCJ6AAAAMAAJ

—————————, The Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia [Mass Market Paperback]. Toronto : McClelland and Stewart, 1937, 1969.

http://www.amazon.ca/Neutral-Yankees-Nova-Scotia/dp/B0030FJYAY

See, eg, the discussion of Ferrall Wade’s 1770s fur trading business in Toronto, funded by William Johnson in what is now Johnsonville, Rensselaer County, upstate New York, in Richard White, The Middle Ground : Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1991, 1993. 2nd edition, 2010, 2012, 334–336.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/middle-ground/5F4044644A763E02CC77F1D90AEF865B

United Empire Loyalist statue and plaque in front of 50 Main Street East, Hamilton, Ontario : THIS MONUMENT IS DEDICATED TO THE LASTING MEMORY OF THE UNITED EMPIRE LOYALISTS … Who, after the Declaration of Independence, came into British North America from the seceded American colonies and who, with faith and fortitude, and under great pioneering difficulties, largely laid the foundations of this Canadian nation as an integral part of the British Empire … Neither confiscation of their property, the pitiless persecution of their kinsmen in revolt, nor the galling chains of imprisonment could break their spirits, or divorce them from a loyalty almost without parallel. “No country ever had such founders —/No country in the world —/No not since the days of Abraham.” (Lady Tennyson).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:United_Empire_Loyalist_statue_and_plaque_in_Hamilton,_Ontario.jpg

United Empire Loyalist Statue … On May 24th, 1929 , a great ceremony was attended by numerous citizens of Hamilton . The unveiling of the United Empire Loyalists statue, which was a generous gift to the city by Mr. Stanley Mills, brought great cheers from the crowd gathered outside the Wentworth County Court House … as above, but also, eg: “The United Empire Loyalists, believing that a monarchy was better than a republic, and shrinking with abhorrence from a dismemberment of the Empire, were willing, rather than lose the one and endure the other, to bear with temporary injustice. Taking up arms for the King, they passed through all the horrors of civil war and bore what was worse than death, the hatred of their fellow-countrymen, and, when the battle went against them, sought no compromise, but, forsaking every possession excepting their honour, set their faces toward the wilderness of British North America to begin, amid untold hardships, life anew under the flag they revered … They drew lots for their lands and with their axes cleared the forest and with their hoes planted the seed of Canada’s future greatness.” — Elizabeth Bowman Spohn.

http://www.myhamilton.ca/articles/united-empire-loyalist-statue

“The United Empire Loyalist Stamp — 1934”.

http://www.uelac.org/Carletonuel/1934stamp.htm

Murray Barkley, “The Loyalist Tradition in New Brunswick: the Growth and Evolution of an Historical Myth, 1825-1914. Acadiensis, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring 1975), pp. 3-45.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/30302493

David J. Cheal, “Ontario Loyalism: A Socio-Religious Ideology in Decline.” Canadian Ethnic Studies/ Etudes Ethniques au Canada. Vol. 13, Iss. 2, (Jan 1, 1981).

https://www.proquest.com/openview/291c7fb2b030441324522926be56ec49/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1817720

Elwood H. Jones, “Loyalist Ideology: Reflections on Political Culture in Early Upper Canada. Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d’études canadiennes. Vlume 29, Number 3, Fall 1994, pp. 163-168.

https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/50/article/673819/pdf

Barry Cahill, “The Black Loyalist Myth in Atlantic Canada,” Acadiensis, vol. 29 no. 1 (Autumn 1999): 76-87.

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/10801/11587

Alan Taylor, “A Northern Revolution of 1800? : Upper Canada and Thomas Jefferson,” in James Horn, Jan Ellen Lewis, and Peter S. Onuf , eds., The Revolution of 1800 : Democracy, Race, and the New Republic. Charlottesville and London : University of Virginia Press, 2002. 383–409.

https://www.upress.virginia.edu/title/2902/

Robert Meynell, “Were the Loyalists Right? Arguing for a Renewed Loyalist Politics in Canada.” Presented at the Canadian Political Science Association Annual General Meeting, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, May 27-229, 2009.

https://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2009/Meynell.pdf

Jane Errington, “Loyalists and Loyalism in the American Revolution and Beyond,” Acadiensis XLI, no. 2 (Summer/Autumn 2012): 164-173.

file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/administrator,+acad41_2re01.pdf

Bonnie Huskins, “Let’s work together: A loyalist historian from Canada responds to American scholars.” Early Canadian History/Historiography, March 10, 2016 at 9:25 am.

https://earlycanadianhistory.ca/2016/03/07/overlooked-loyalists/

F.S. Rivers, C.C. Goldring, and Gilbert Paterson, The Empire Story. Grade VIII. The Guidebook Series in Social Studies. Toronto : The Ryerson Press, 1939. Inevitably much in this late 1930s Ontario “Grade VIII” text book now seems absurd. But it does have early modern moments, eg : “the Empire … includes white men, black men, yellow men, brown men …” Still just men, no women, of course, and white men are first, but a start?

Pierre Berton, The Invasion of Canada 1812–1813. Toronto : McClelland and Stewart, 1980. (See pp 28–29 for “the myth of the war … Canada would not become a part of the Union to the south”… etc. )

https://www.amazon.ca/Invasion-Canada-1812-1813-Publisher-McClelland/dp/B00G3YZ80Y

______________, Flames Across the Border 1813–1814. Toronto : McClelland and Stewart, 1981. (On “Great Britain wants an Indian buffer state … etc” see pp. 405–419.)

https://www.amazon.ca/Flames-Across-Border-Pierre-Berton/dp/0385658389

On the “controversial Samuel Eliot Morison” who “quotes the Virginia Congressman John Randolph” see Samuel Eliot Morison, The Oxford History of the American People. New York : Oxford University Press, 1965, 380.

http://www.amazon.ca/The-Oxford-History-American-People/dp/0195000307

Francis Parkman, The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War After the Conquest of Canada. Volumes I, II. Toronto : George N. Morang, 1851, 1870, 1899.

Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812 : American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies. New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

https://www.abebooks.com/9781400042654/Civil-1812-American-Citizens-British-1400042658/plp

__________, The Civil War of 1812 : American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies. Toronto : Penguin Random House Canada, 2011.

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.ca/books/176724/the-civil-war-of-1812-by-alan-taylor/9780679776734

https://www.amazon.ca/Civil-War-1812-American-Citizens/dp/0679776737

Daniel Schwartz, “Historian Alan Taylor’s new take on the ‘civil war’ of 1812.” CBC News · Posted: Jun 13, 2012 8:56 AM EDT | Last Updated: June 13, 2012.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/historian-alan-taylor-s-new-take-on-the-civil-war-of-1812-1.1277948

Wikipedia, “Tecumseh.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tecumseh

CBC News, “’New landmark’ celebrated at dedication of Chief Tecumseh sculpture … The sculpture is on the beach at Lakewood Park North.” Posted: Jul 03, 2023 8:24 PM EDT | Last Updated: July 3, 2023.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/tecumseh-sculpture-dedicated-1.6896078

Canadian National Historic Sites, “Tecumseh Monument, Thamesville, Ontario,” Date Posted: 10/10/2008.

http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM4XHM_Tecumseh_Monument_Thamesville_Ontario

White, The Middle Ground , 517.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/middle-ground/5F4044644A763E02CC77F1D90AEF865B

Harold A. Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada : An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. New Haven : Yale University Press, 1930, 397; Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 1956, 1970, 392.

Berton, The Invasion of Canada 1812–1813, 26.

https://www.amazon.ca/Invasion-Canada-1812-1813-Publisher-McClelland/dp/B00G3YZ80Y

White, The Middle Ground, 268.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/middle-ground/5F4044644A763E02CC77F1D90AEF865B