100th anniversary of Easter 1916 Rebellion in Ireland .. one view from Toronto, Canada

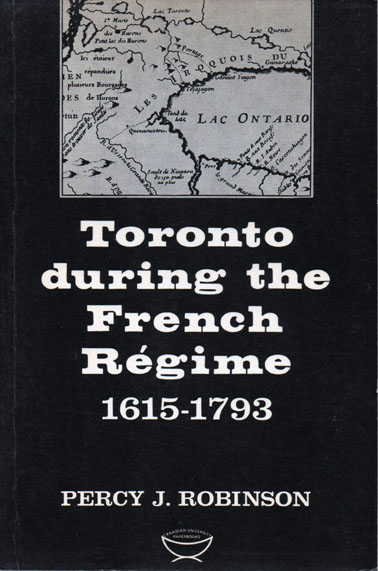

Mar 27th, 2016 | By Dominic Berry | Category: Countries of the World In the 1930s the local historian (and private school Latin teacher) Percy Robinson – author of the still invaluable Toronto during the French Regime, 1615—1793 – called Toronto, Ontario, Canada (all North American indigenous words) “the citadel of British sentiment in America.”

In the 1930s the local historian (and private school Latin teacher) Percy Robinson – author of the still invaluable Toronto during the French Regime, 1615—1793 – called Toronto, Ontario, Canada (all North American indigenous words) “the citadel of British sentiment in America.”

On a somewhat earlier and more extreme, possibly even exaggerated variation on the theme it was “the Belfast of North America.” And, exaggerated or otherwise, it is a nowadays awkward plain truth that in 1914, on the eve of the First World War, two-thirds of Toronto city council belonged to the Loyal Orange Lodge.

This old song has largely ended in 2016. But “Orangemen” still dominated city council until the 1960s – or at least until the “Mayor of All the People” Nathan Phillips, 1955—1962, a decade and more after the Second World War. And even today, in the aftermath of subsequent vast diverse migrations from all over the global village, something of the melody lingers on – and sometimes in surprising places.

(Just two examples : The South Asian Bollywood Toronto of the early 21st century, with its own history in the empire on which the sun never dared to set, is in some ways a quite logical descendant of the old British Toronto of the early 20th century. Â And much of the Caribbean community in Toronto today has parallel roots in the old British West Indies.)

(Just two examples : The South Asian Bollywood Toronto of the early 21st century, with its own history in the empire on which the sun never dared to set, is in some ways a quite logical descendant of the old British Toronto of the early 20th century. Â And much of the Caribbean community in Toronto today has parallel roots in the old British West Indies.)

For all these and other reasons, perhaps, the 100th anniversary of the Easter 1916 Rebellion in Dublin – the great bloody failed sacrifice that, on some accounts at any rate, finally gave birth to the Irish republic some two (or three) decades later – is not exactly something in the air even in the Toronto where I live in 2016.

Yet the “Buffalo/Toronto” PBS station, which broadcasts to Southern Ontario as well as Western New York, did run an evening-long look at the history of “Easter 1916” in Dublin a few days ago. And Toronto has had an annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade now since 1988.

At Canadian confederation in 1867 Irish Catholics who had fled the Great Famine in the Emerald Isle accounted for as much as a quarter of the Toronto population. And a 19th century tradition of brawling between Green Irish Catholics and Orange Irish Protestants on St. Patrick’s Day apparently prompted the Orange-dominated city council to ban St. Patrick’s Day Parades in 1878. In the old Toronto of the later 19th and earlier 20th centuries the rival related big event was the Orange Parade on July 12.

Even so, the present iconic Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team was actually known as the Toronto St. Patricks from 1919 to 1927. And the police detective in the current Canadian TV series Murdoch Mysteries, allegedly set in late 19th and early 20th century Toronto, is an Irish Catholic – like the iconic Toronto novelist and short story writer Morley Callaghan, who once knocked out Ernest Hemingway in a boxing match in Paris!

In 2016 as well there are those among us who still follow the wider world by keeping one eye on New York and the other on London (along with such other more Pacific century places as San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, Honolulu, Â Melbourne, Mumbai, Shanghai, Tokyo … oh and Paris, Rome, and much more in other directions too).

And some of us received via email a few days ago a new article from the London Review of Books called “After I am hanged my portrait will be interesting … Colm TóibÃn tells the story of Easter 1916.” (Which early on sketches the career of O’Donovan Rossa of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, aka Fenians : “In January 1881 his followers exploded a bomb in Salford, the first time a bomb had been planted in Britain to further a political cause.”)

1. What does Easter 1916 mean for playboys of the western world and beyond in 2016?

Colm TóibÃn is a 60-something “Irish novelist, short story writer, essayist, playwright, journalist, critic and poet,” whose paternal grandfather was a member of the IRA and took part in the 1916 Rebellion. And in his London Review of Books piece he offers a nicely crafted summary of just what “Easter 1916” was and was not all about, from the standpoint of the early 21st century :

(1) It all begins in the 1880s with “the movement to bomb Britain,” to further the cause of an Irish republic independent from the United Kingdom. The movement’s “culmination was Dynamite Saturday in January 1885.” As reported by the American novelist Henry James, then resident in London : “The country is gloomy, anxious, and London reflects its gloom. Westminster Hall and the Tower were half blown up two days ago by Irish Dynamiters.”

(2) Patrick Pearse (who “had kept a school”) – Â a key figure in what finally became “Easter 1916” – wrote in 1913 that “it is a goodly thing to see arms in Irish hands … We may make mistakes at the beginning and shoot the wrong people; but bloodshed is a cleansing and sanctifying thing, and the nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.”

(3) On Easter Monday 1916 “rebels took the General Post Office in Dublin. A republic was declared … It was Pearse … who read out the Proclamation … Its seven signatories included Pearse himself, Clarke, MacDonagh and MacDermott … ‘There was very little noise in the street – practically silent,’ one witness recalled … ‘The crowd numbered about two hundred and I’m sure that many of them didn’t recognise the significance of what Pearse was saying … there was no reaction’ … Â Another witness reported: ‘Slowly the crowd broke up … Quite a few, bored with the whole affair, simply turned and wandered away’ … Â ‘The people simply listened and shrugged their shoulders … ’the writer Stephen McKenna recorded. Within a week, however, the Chicago Tribune reported that when Pearse finished speaking ‘thundering shouts rent the air, lasting for many minutes. The cries were taken all along Sackville Street and the adjoining thoroughfares.’” (And people complain about truth and the media today … !)

(3) On Easter Monday 1916 “rebels took the General Post Office in Dublin. A republic was declared … It was Pearse … who read out the Proclamation … Its seven signatories included Pearse himself, Clarke, MacDonagh and MacDermott … ‘There was very little noise in the street – practically silent,’ one witness recalled … ‘The crowd numbered about two hundred and I’m sure that many of them didn’t recognise the significance of what Pearse was saying … there was no reaction’ … Â Another witness reported: ‘Slowly the crowd broke up … Quite a few, bored with the whole affair, simply turned and wandered away’ … Â ‘The people simply listened and shrugged their shoulders … ’the writer Stephen McKenna recorded. Within a week, however, the Chicago Tribune reported that when Pearse finished speaking ‘thundering shouts rent the air, lasting for many minutes. The cries were taken all along Sackville Street and the adjoining thoroughfares.’” (And people complain about truth and the media today … !)

(4) “Over the last hundred years there has been much discussion about the rebellion in Dublin that began on Easter Monday and ended with unconditional surrender the following Saturday. It involved the destruction of the city centre and the deaths of almost five hundred people, just over half of them civilians, some of them children. Very soon after the rebellion ended, what McGarry calls ‘a powerful narrative emerged … the Rising was seen as a heroic fight by selfless patriots who had recklessly taken on the might of the British Empire, the nobility of their cause and vindictiveness of the British response resurrecting a quiescent Irish nation.’ According to this narrative, the 1916 Rising led directly to Sinn Féin’s spectacular victory in the 1918 election, the ensuing guerrilla war against Britain, and Irish independence.”

(5) “More recently, historians have offered other narratives … Another historian, David Fitzpatrick, has commented … ‘By raising their tricolour in the centre of the main shopping area and close to Dublin’s northside slums, the rebels ensured massive human and material losses once their position was attacked. It is difficult to avoid the inference that the republican strategists were intent upon provoking maximum bloodshed, destruction and coercion, in the hope of resuscitating Irish Anglophobia and clawing back popular support for their discredited militant programme.’”

(6) “The British were surprised by the Rebellion … They followed earlier failure with a sudden burst of energy, handing over effective power in Ireland to the military, arresting 3430 men and 79 women and raiding houses throughout the country. In a series of court martials they sentenced 90 rebels to be shot. Fifteen of these sentences were quickly carried out …Among those shot by firing squad were Pearse, Clarke, MacDonagh, MacDermott and Edward Daly, Clarke’s brother-in-law … As early as 3 May – the day Clarke, Pearse and MacDonagh were shot – Redmond protested to Asquith, the prime minister, that ‘if any more executions take place in Ireland, the position will become impossible for any Constitutional Party …’ On 10 May Asquith sent instructions to Dublin that ‘no further executions are to take place until further orders.’”

(7) “Despite … Asquith’s instructions, Connolly and MacDermott were shot on 12 May … On 3 August, Roger Casement was hanged in London … Around 1600 prisoners were transferred from Ireland to England. They were held as ‘enemy aliens’, which some considered strange since they were indisputably British citizens, or would be until six years later, when the British left Southern Ireland, having made every further mistake possible: losing the support of the Catholic Church, continuing the threat of conscription and sending in the Black and Tans, a force not known for its restraint or discipline, to attempt to pacify the country.”

(8) After the fact, the Irish poet who became a gift to English literature, William Butler Yeats, finally wrote “‘Easter 1916’, a poem which … seems to give the leaders of the Rebellion heroic status and in its repetition of the line ‘a terrible beauty is born’ appears to make the Rebellion itself iconic, almost noble. But in the last two stanzas, in a number of startling images, Yeats had much to question, much to say about the idea of violence and violent insurrection and nationalism.”

(9) Seán O’Casey, who would finally write a play about “Easter 1916” in the mid-1920s (The Plough and the Stars) “had also drafted a constitution for the Irish Citizen Army early in 1914 that would have distinct echoes” in Patrick Pearse’s 1916 Proclamation in front of the General Post Office in Dublin. “‘That the first and last principle of the Irish Citizen Army,’ O’Casey wrote, ‘is the avowal that the ownership of Ireland, moral and material, is vested of right in the people of Ireland.’ The Proclamation, which Pearse read in front of the GPO on Easter Monday 1916, included the sentence: ‘We declare the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies, to be sovereign and indefeasible.’”

(10) “So, as the afterglow of the Rebellion continued to shine, the best-known poem about it wasn’t published until four years after its composition, and the best-known play caused riots and walkouts. The rhythmic energy in Yeats’s ‘Easter 1916’ and the hilarity and pathos in The Plough and the Stars partly arose from their authors’ involvement not only in an argument with themselves but in an argument with a powerful myth about the value of political violence and blood sacrifice, which was slowly becoming dominant.”

Historic speech by Irish rebel leader Patrick Pearse at the graveside of Fenian leader O’Donovan Rossa, 1915 – commemorated by Irish stamp in 2015. Pearse is to the right, dressed in military uniform and holding his hat.

(11) “By the time they sat in their prison cells in the early hours of 3 May 1916 awaiting execution, it was clear that Clarke and Pearse had divided public opinion in Britain and Ireland in a way that would come to matter. They appeared to the British as supremely treacherous. They had stabbed the country in the back during a time of war … It was hard to imagine, if viewed from the British side, what else could have been done with the leaders of the rebellion. It must have seemed not only natural, but just and right, to shoot them.”

(12) “But the rebels appeared to the Irish side in a totally different light. The stark divergence in this after-image – Â the creation of a deep fissure between Britain and Ireland – Â was perhaps the rebels’ real achievement … Clarke and Pearse and their followers, despite their fanaticism, had somehow managed to present themselves in Ireland as noble spirits … Once they were shot, they became, as Yeats suggested, changed, oddly heroic … the night before his execution Pearse composed a poem about the beauty of the world which we all learned in school fifty years after his death. He also wrote a letter to his mother. In it he said … ‘This is the death I should have asked for if God had given me the choice … Â to die a soldier’s death for Ireland and for freedom.’

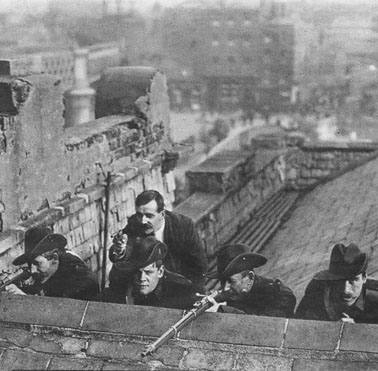

Archive image of Irish Citizen Army fighters on a Dublin rooftop during the Easter Rising 1916. (Image Camera Press Ireland.)

On Easter Sunday 2016 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada it also seems hard not to notice some similarity between the “powerful myth about the value of political violence and blood sacrifice” in early 20th century Ireland and “international jihadism” today.

It seems hard not to notice as well that the virulent response of British authorities to the “political violence and blood sacrifice” of the 1916 Irish rebellion – Â the executions and then the Black and Tans – Â had almost exactly the opposite ultimate impact on events to the one the virulent response intended. Â (The Black and Tans were similarly one legendary nemesis of the progressive political tradition in old Toronto, as I remember hearing long ago from the left-wing father of a friend in high school.) Somewhere here there are lessons about responding to violent political protest (and “international jihadism”) today that still go largely unheeded.

2. Easter 1916 in Ireland and the Reluctant Canadian Republic in Toronto in 2016

There are still those who just cannot take seriously the notion that there is a Canadian republican movement with two active organizations in Toronto today. But there is, nonetheless.

There are still those who just cannot take seriously the notion that there is a Canadian republican movement with two active organizations in Toronto today. But there is, nonetheless.

Its ultimate objective is “the replacement of the non-resident British monarch as Canada’s head of state with a democratically-selected, resident Canadian.” Â And intellectual and political honesty oblige me to confess that I am among the strong supporters of this goal. Especially when the present widely respected British monarch sadly passes from the scene. (And see here also some recent musings from Malcolm Turnbull, Australian republican PM of Canada’s fellow former British dominion down under.)

FACING UP TO THE CONFEDERATION’S “DREADFULLY TORY” CONSTITUTION OF 1867 AT LAST

None of this is to deny that, as George Brown of the Globe wrote to his wife long ago, what we now call the Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly the British North America Act, 1867 – a law of the Parliament of the United Kingdom) is, in some respects still, a “dreadfully Tory” constitution. But …

None of this is to deny that, as George Brown of the Globe wrote to his wife long ago, what we now call the Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly the British North America Act, 1867 – a law of the Parliament of the United Kingdom) is, in some respects still, a “dreadfully Tory” constitution. But …

To start with, as explained some time ago by the late, great George Woodcock from BC (via Winnipeg and the UK), the old British North America Act, 1867 (and current Constitution Act, 1867) was just “a makeshift document cobbled together by colonial politicians.” It ought to be amended soon enough in the 21st century, and it is a leading article of the Canadian republican faith that it will be – and quite possibly sooner than many think (maybe, of course : Canada will always be a complicated and diverse place, politically and every other way too, etc) …

Moreover, a great many things about both Canada and the wider global village have changed dramatically since 1867. And the “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom” established by the old British North America Act also established a still largely “unwritten” and flexible fundamental governmental order, with a long tradition of adapting to and even innovating for changing times, without changing any exact letters of old laws.

Moreover, a great many things about both Canada and the wider global village have changed dramatically since 1867. And the “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom” established by the old British North America Act also established a still largely “unwritten” and flexible fundamental governmental order, with a long tradition of adapting to and even innovating for changing times, without changing any exact letters of old laws.

And then the father of the current Canadian prime minister finally managed to quite peacefully “patriate” the written part of the Canadian Constitution from the United Kingdom, via the Constitution Act, 1982 and its Canadian Charter of Right and Freedoms.  (In the wake of the failure of the first Quebec sovereignty referendum in 1980 – after a long wind-up stretching back into the early 1960s, and including our own Canadian early flirtations with powerful myths about “the value of political violence and blood sacrifice” – in the Front de libération du Québec [FLQ] and the October Crisis of 1970.)

THE CONSTITUTION ACT, 1982 AND THE RISE OF THE RELUCTANT REPUBLIC

Canadian patriot Pamela Anderson shows how Canada still has a lot to offer in 2016, even or especially without the British monarch as colonial head of state.

In any event, for Canadian republicans today the point about the dreadfully Tory constitution inherited from the colonial past is that (as George Brown also wrote to his wife long ago) “we have the power in our hands … to change it as we like.” Â And this was at least finally realized in the written part of the constitution by the (admittedly too quaintly complex) amending formulae of the Constitution Act, 1982 (which have nonetheless worked already, on several occasions!).

And then we have political scientist Frederick Vaughan’s interesting and helpful book of 2003 (even if I don’t at all agree with every word of it) : Â The Canadian Federalist Experiment : From Defiant Monarchy to Reluctant Republic.

(Vaughan “argues that Trudeau’s 1982 Charter quietly undermined the monarchic character of the constitution by introducing republican principles of government. The result has been old institutional structures at odds with the republican ambitions, leaving Canada clinging to the wreckage of the old aristocratic order while attempting to provide a new order founded on republican equality.”)

I could go on, but this is already too long ! The bottom line is what, if anything, does the 100th anniversary of  “Easter 1916” in Ireland mean for the Canadian republican cause today? And the main answer here is almost certainly not very much.

MODERN CANADIAN TRADITION OF NO BLOODSHED

Reading Colm TóibÃn’s piece in the London Review of Books, it did occur to me at some points that the failed Irish rebellion of 1916 has a few strange things in common with the failed Upper Canada and Lower Canada rebellions of 1837—38 in North America.

And as noted by my counterweights editorial colleagues some dozen years ago now, just after the arrival of the independent Canadian maple leaf flag in 1965, “the visiting president of the Irish Republic Eamon de Valera apparently told Lester Pearson … that real national flags have to be baptized in blood. And the only real blood involved in the birth of Canada’s flag was the sort that Winston Churchill had in mind, when he said: ‘Politics is almost as exciting as war, and even more dangerous. In war you can only be killed once, but in politics many times.’”

Canada’s flag has subsequently become a serious enough binding force in today’s Canadian parliamentary democracy without any domestic bloodshed at all.

And Canada will finally become a parliamentary democratic republic in the contemporary Commonwealth (and La francophonie) without any domestic bloodshed at all. That is the modern Canadian way.

THE MOST DEMOCRATIC MODEL FOR CEREMONIAL HEAD OF STATE IN A PARLIAMENTARY DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC

What happened, however, after “the 1916 Rising led directly to Sinn Féin’s spectacular victory in the 1918 election, the ensuing guerrilla war against Britain, and Irish independence” is still of some interest to Canadian republicans in 2016 :

Irish Free State with governor general 1922. Very briefly, in 1922 a political entity known as the Irish Free State – in the twenty-six counties of southern Ireland (the six counties of northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom) – became a self-governing dominion of the British Commonwealth, like Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and the Union of South Africa. And the head of state of this Irish Free State was a governor general theoretically accountable to the British monarch (a 19th century colonial concept still in use in Canada, Australia, and 13 other places today) .

Eire with elected ceremonial president 1937. Then in 1937 the government of the Irish Free State  introduced a new constitution. This replaced “the governor general with a [strictly ceremonial] president, elected by the Irish people. And it changes the name of the nation from the Irish Free State to Eire (Gaelic for Ireland) … In spite of vociferous protests from northern Ireland, the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, accepts the constitutional changes …”

Ceremonial president of the Republic of Ireland 1949. Finally, in 1948 the government of Eire introduced “the Republic of Ireland bill –  severing the last constitutional connection with the United Kingdom.” The resulting act of the Dáil or Irish parliament “announces the withdrawal of the twenty-six counties from the Commonwealth and transfers to the Irish president all the functions previously performed by the British crown.” It also “declared that the description of the State shall be the Republic of Ireland.” It “was signed into law on 21 December 1948 and came into force on 18 April 1949, Easter Monday, the 33rd anniversary of the beginning of the Easter Rising.”

It may well be that the Canadian republic of the 21st century will finally come into being through some similar staged process – which could at least begin to get under way after the passing of the present much-admired Queen Elizabeth II.

Eugenie Bouchard celebrates her win against Jana Cepelova of Slovakia during the third match at the Fed Cup in April 2014. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jacques Boissinot.

And (along with the parallel appearance of the new independent Republic of India as the first Commonwealth republic in 1950) the replacement of  “the governor general with a [strictly ceremonial] president, elected by the Irish people” has since 1937 set a successful precedent for the more general transformation of former British dominions that blended parliamentary democracy and colonial constitutional monarchy into parliamentary democratic republics in the modern Commonwealth (that has now succeeded the old global-village-empire on which the sun once never dared set).

That, it would seem, is the largest significance of the 100th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rebellion in Ireland for Canada today, in 2016. Whatever else it may or may not have done, the republican movement in Ireland finally came up with the most democratic model for replacing “the non-resident British monarch as Canada’s head of state with a democratically-selected, resident Canadian.”

NOTES ON SOURCES

Counterweights Editors, “Canada Day 2009 : Percy Robinson and the reluctant Canadian republic.” Â Jun 28th, 2009.

Brock Millman, “Toronto the Belfast of North America,” University of Toronto Press, 2016.

William J. Smyth, Â Toronto, the Belfast of Canada: The Orange Order and the Shaping of Municipal Culture, University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Nathan Phillips (politician) … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Carola Vyhnak, “Once Upon a City: Why St. Patrick’s Day parade was banned for 110 years …Â Feuding between Catholic and Protestant Irishmen erupted in 1878 into “one of the wildest nights in the city’s history,” Toronto Star, Sat Mar 12 2016.

Toronto St. Patricks … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Carola Vyhnak, “Once Upon a City: Morley Callaghan both loved and lost in Toronto … A look back on his life on the 25th anniversary of his death tells the story of a Toronto wordsmith who waited years to be feted as one of Canada’s literary treasures,” Toronto Star, Thu Aug 20 2015.

1. What does Easter 1916 mean for playboys of the western world and beyond in 2016?

John Millington Synge, The Playboy of the Western World … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Abbey Tavern Singers, “We’re Off to Dublin in the Green” (IRA Marching Song), 1966.

Colm TóibÃn … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Colm TóibÃn, “After I am hanged my portrait will be interesting,” London Review of Books, 31 March 2016.

William Butler Yeats, “Easter 1916.”

Seán O’Casey, The Plough and the Stars … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Mark Lilla, “How the French Face Terror” (on “international jihadism”), New York Review of Books, March 24, 2016.

2. Easter 1916 in Ireland and the Reluctant Canadian Republic in Toronto in 2016

Citizens for a Canadian Republic.

Republic Now || République du Canada.

“Malcolm Turnbull says now not time for Australian republic: We must wait until Queen leaves throne,” The Daily Telegraph, January 26, 2016.

Frederick Vaughan, The Canadian Federalist Experiment : From Defiant Monarchy to Reluctant Republic, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003.

Christopher Moore, Â 1867: How the Fathers Made a Deal, McClelland & Stewart, 1997.

Front de libération du Québec … From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Counterweights Editors, “Flapping the flag in Newfoundland and Labrador.. a holiday sport,” Dec 31st, 2004. “ … the the visiting president of the Irish Republic Eamon de Valera apparently told Lester Pearson … that real national flags have to be baptized in blood …”

“Guelph’s Joe Tersigni offers a history lesson on the Maple Leaf flag,” Guelph Mercury, Fri., Feb 06, 2015. “president Éamon de Valera of Ireland warned him that …  ‘To get a new flag accepted, you have to have blood on it.’”

History World, “HISTORY OF THE REPUBLIC OF IRELAND.”