Maybe new Advisory Board for Senate Appointments in Canada should experiment with selection by lottery too

Oct 28th, 2016 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

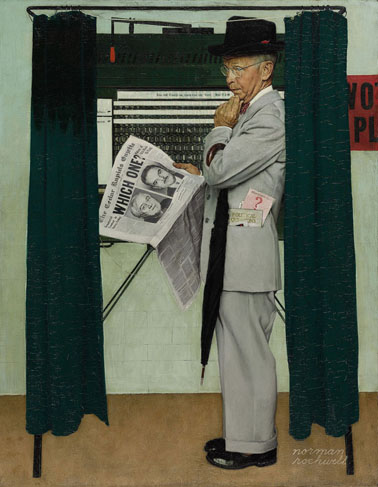

Norman Rockwell’s 1944 painting “Which One? (Undecided; Man in Voting Booth),” which was a cover for The Saturday Evening Post during the presidential race between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Thomas E. Dewey. Credit SEPS licensed by Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN, via Sotheby’s. All rights reserved.

The juxtaposition of the last days of the twisted 2016 US election campaign and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s latest round of “independent” appointments to the still seriously unreformed Senate of Canada casts some harsh light on what the new Liberal government in Ottawa is trying to do with this archaic Canadian institution – still too much modelled on the 19th century British House of Lords.

This past February the Hamilton Centre New Democrat MP David Christopherson told a Commons standing committee that he’s worried the Trudeau government’s new Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments will just “end up perpetuating an elitist system.” Mr. Christopherson “would like somebody in there who knows what it’s like to get up every day and get their fingernails dirty for a living.”

In fact, the main theory behind the new Board and its “Merit-based criteria” for recommending Senate appointments to the prime minister is that the Senate should be a place for people who have distinguished themselves and become part of one or another kind of non-political elite in their community. The assumption is that this kind of person can best inject some “sober second thought” into more politically charged legislation passed by the popularly elected Canadian House of Commons.

In this spirit the latest round of new appointments includes a senior fellow in public policy at UBC, a Manitoba art historian, a Winnipeg psychiatrist and internationally recognized expert in palliative care, a lawyer and human rights activist, the president of the Societe Nationale de L’Acadie, a New Brunswick women’s issues expert, a Nova Scotia social worker and educator, a senior adviser for the Mi’kmaw First Nation of Membertou, NS, and a Prince Edward Island conservationist and former provincial deputy minister.

Yet one of the things the twisted 2016 US election campaign seems to be telling us is that large swaths of the mass base of our kind of democracy have become quite alienated from all manner of elite expertise. A still merely appointed Senate of Canada that cultivates any kind of elitism is not really going to seem more legitimate than the present Senate, with all its traditional ties to partisan political patronage on the old discredited 19th century Canadian model.

All this just underlines the current relevance of a question David Christopherson put this past February to Huguette Labelle, chair of the new Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments : “How do we avoid the continuation of the view that the Senate is full of elites?”

* * * *

The popularly elected Australian Senate at work. As in Canada the Senate Chamber in the Land of Oz  is decorated in red.

One immediate and obvious answer of course would be to turn the current Senate of Canada into a popularly elected institution – on the model of the US and Australian Senates. Yet neither the US nor Australian Senate is all that popular in its homeland at the moment. And in any case, as Stephen Harper finally discovered, to establish an elected Senate in the true north of North America you would have to wade into the great Canadian constitutional swamp. The Trudeau government is not interested. It just wants to neutralize the Senate as an issue, for the more immediate future. Sunny ways also mean avoiding deep troubled waters, including swamps.

But there is another answer to David Christopherson’s question about avoiding elites. And it may fit more easily into the current limited-change objectives of Ms Labelle’s Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments – which has already invited interested ordinary Canadians to apply for work.

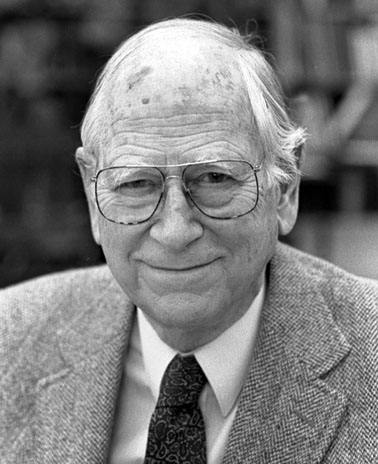

“Robert A. Dahl, 98, an esteemed and influential political scientist who in such books as ‘Who Governs?’ championed democracy in theory and critiqued it in practice” passed away early in February 2014.

Back in the late 20th century the American political scientist Robert A. Dahl (1915—2014) – perhaps anticipating some of the democratic challenges that have surfaced with particular clarity in the  twisted 2016 US election campaign – noted the uses of “selection by lot” to fill offices in the ancient democracies of classical Greece.  And he proposed “we seriously consider restoring that ancient device and use it for selecting advisory councils to every elected official of the giant polyarchy,” that has come to define our representative democracy today.

Similar proposals have already been made with regard to the Senate of Canada. In 2011a reddit post “Okay, how about Senate by lottery?” was active for a short while on the net. The proponent(s) explained : “Similar to jury duty, people from each region of the country would be selected randomly from a list of eligible citizens. Anybody who couldn’t serve” would have to “give a legitimate reason they couldn’t serve … Credit goes to black_as_nails for the idea.”

In 2012 Â Devin Penner, then a PhD candidate at York University in Toronto, and now an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Studies at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, presented a paper called “Beyond Triple-E and Abolition: A Radically Democratic Third Option for Senate Reform,” at the annual Canadian Political Science Association Conference (in Edmonton that year). This paper also argued for a Canadian Senate selected randomly by lottery, on the ancient Greek democratic model.

Consummate old Ottawa pro Huguette Labelle, now chair of the new Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments.

Whether one might want an entire Senate selected randomly by lottery, as with jury duty, could be a poignant question. But it also seems arguable that Huguette Labelle’s new Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments might experiment with periodically recommending a few Canadian Senate candidates selected randomly by lottery to the prime minister – as may be required down the road. The prime minister just might similarly decide to appoint a few Senators selected this way. And that could go at least some distance to answering David Christopherson’s question of this past February about avoiding elites. It could even start to make the Senate in Ottawa a more seriously interesting and innovative new kind of democratic institution as well.

Randall White is the author of a number of books on Canadian history and politics, including Voice of Region : The Long Journey to Senate Reform in Canada. He has a PhD in political science from the University of Toronto, and spent a dozen years in the Ontario public service. For the subsequent three decades he worked as an independent public policy consultant for a wide variety of public and private sector clients. He also contributes to the Ontario News Watch website today, and serves on the editorial advisory committee of the journal Ontario History.