Canada has its own populisms .. and rebellions – in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan!

Mar 23rd, 2017 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

Last week the irrepressible Preston Manning had an article in the Globe and Mail on how “Canada’s elites could use a crash course in populism.”

He cited  Tom Flanagan’s Waiting for the Wave and W. L. Morton’s The Progressive Party in Canada as useful reading for any elites actually wanting to take the course he recommends.

Not surprisingly, he did not cite such related volumes as S.M. Lipset’s Agrarian Socialism : The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in Saskatchewan (1950, 1971) or C.B. Macpherson’s Democracy in Alberta : Social Credit and the Party System (1953, 1962, 2013).

(Mr. Manning is a right-wing rather than a left-wing populist – and both the Lipset and Macpherson books are broadly left-wing.)

There are nonetheless two passages in Preston Manning’s piece that strike me as probably worth repeating. The first is : “it is probably safe to say that Canada’s political and media establishment have never really understood populism in this country and are therefore ill-equipped to understand or respond to its current manifestations.”

(Well … One finer point I have trouble with here is that, to me, Canada – happily enough – has a number of political and media establishments : one of which may actually include Preston Manning, and another of which speaks French, etc, etc. Mr. Manning occupies more solid ground when he focuses on … “Ottawa” say.)

My second worth-repeating passage in “Canada’s elites could use a crash course in populism” is just the article’s concluding paragraph (which does finally land on more solid ground) :

“Canada has had its own past experience with populism – some of it bad, much of it good, but all of it instructive. Given the uprising of populist sentiment in our times, today’s politicos and pundits would be wise to revisit and learn from that extensive and instructive experience. Failure to do so, especially at the national level, could mean that Ottawa will be the next capital city to be the last to know what is going on.”

I would (I should make clear, in the interests of science) never vote for or otherwise politically endorse Preston Manning. But I do think there is wisdom in these two quoted passages from his recent Globe and Mail article.

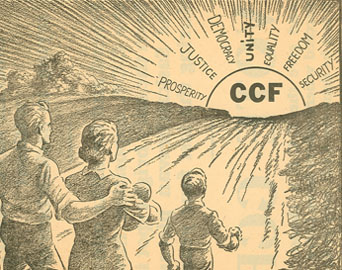

Early CCF ad. Tommy Douglas’s CCF government in Saskatchewan, first elected in 1944, pioneered public health care in Canada – supported federally with the Medical Care Act of 1966.

At the same time, to me there is still something crucial that is missing in Mr. Manning’s crash course as well. And, to seriously instruct today’s politicos and pundits who haunt the bars and restaurants of the Sparks Street Mall, the Byward Market, Elgin Street, and on and on it should be included.

When Preston Manning talks about populism in the adjacent United States, for instance, he alludes to two figures from the 19th century – Andrew Jackson and William Jennings Bryan. But in his Canadian examples he sticks to the 20th century, which he knows directly himself.

Canadian populism in the 20th century, however, has its own 19th century ancestors. And all our 21st century  political and media establishments could probably profit from pondering them somewhat more deeply than usual, during the 150th anniversary year of the 1867 confederation.

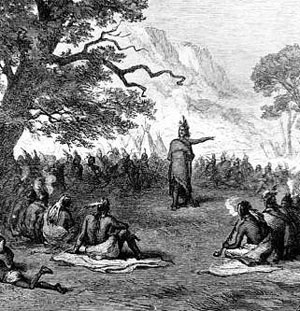

Painting of the Assembly of the Six Counties by Charles Alexander Smith. The Assembly of the Six Counties / Assemblée des six-comtés was a gathering of “Patriotes” held in Saint-Charles, Lower Canada on October 23 and October 24, 1837, despite a June 15 Proclamation of the government forbidding public assemblies. It was the most famous of various public assemblies that became a prelude to the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837—38.

To make a potentially quite long story very short, I’m just talking about the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837—1838, the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, the First Riel or Red River Rebellion of 1869—1870, and the Second Riel or Northwest Rebellion of 1885.

Many further things could be said about the 19th century rebellions in Canada – which at least strike me as crucial precursors of all 20th century (and beyond) Canadian populisms. Â But that might just confuse things unnecessarily for the moment.

In any case, click on “Read the rest of this page” and/or scroll below for four further quick notes, on : (1) The Rebellion Tradition in Canada Matters (too) ; (2) Louis Riel and Justin Trudeau ; (3) 18th century ancestor – “The Conspiracy of Pontiac” ; and (4) Another late 20th century descendant : the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution Act, 1982.

(1) The Rebellion Tradition in Canada Matters (too)

Ever since the conservative Nova Scotian “politician, judge, and author” Thomas Chandler Haliburton dismissed the 1837—38 rebellions as The Bubbles of Canada in 1839, various subsequent political and media establishments have belittled their importance.

C.W. Jefferys’ famous enough sketch of the December 5 march down Yonge Street in the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, with the image somehow reversed, or switched from left to right! Not for the last time angry people would try to attack the provincial capital in Toronto.

This was not the attitude of many alive at the time. When the Upper Canada Rebellion leader William Lyon Mackenzie died in Toronto, eg, late in August 1861, the Globe (precursor of today’s Globe and Mail) editorialized : “It must be reiterated that insurrection was the immediate cause of the introduction of a new system. It might have been gained without rebellion but the rebellion gained it.”

The “new system” alluded to by the Globe here has traditionally been called “responsible government.” It marked the beginnings of self-governing parliamentary democracy in the old British North American provinces. And it arrived in 1848 (aka the “year of revolution” in Europe), to no small extent as a result of the 1837—38 rebellions.

All this has been explored a littler further in various places on this website, including : “175th anniversary of 1837 rebellions more important for Canadian democracy today than War of 1812” (Dec 4th, 2012) ; Â “The beginnings of various regional democracies in what is now Canada, after the War of 1812” (Aug 21st, 2015) ; and “The Canadian boom of the 1850s and the road to Confederation, 1848—1864” (Feb 19th, 2016).

(2) Louis Riel and Justin Trudeau

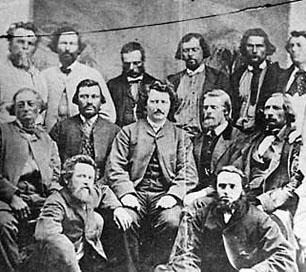

Louis Riel used to be a controversial figure in Canadian history. One sign of his more recent rehabilitation and enhanced status was the establishment in 2008 of a public holiday in the province of Manitoba known as Louis Riel Day, on the third Monday of February.

(A holiday also now held on the same  third Monday of February is much less imaginatively known as Family Day in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, as Nova Scotia Heritage Day in Nova Scotia, and Islander Day in Prince Edward Island. And another version of Louis Riel Day is celebrated by some of his Canadian Métis descendants on November 16 – the day he was finally hanged for treason by the Ottawa-based federal government, on a cold Regina morning  in 1885.)

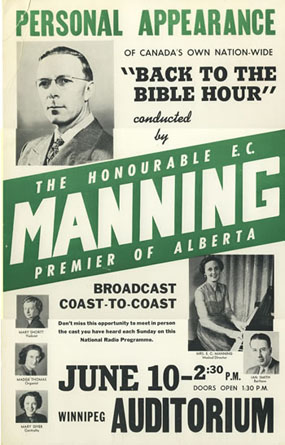

Louis Riel (standing centre) addresses the court during his trial for treason in Regina, summer 1885. Courtesy of the National Archives of Canada.

I have recently been personally forced (so to speak) to come to grips with the legacy of Louis Riel in Canada  today as part of a current book project. See : “First self-governing dominion of the British empire : Further founding moments, 1867—1873” (Sep 15th, 2016) ; and “Arduous Destiny : Canada’s alternative to the Great Barbecue, 1873-1896” (Mar 8th, 2017).

Of much greater consequence Justin Trudeau – first as Liberal Party of Canada leader and then as prime minister – issued quite glowing statements about Louis Riel’s Canadian legacy for Manitoba’s Louis Riel Day on : February 17, 2014 ; Â February 16, 2015 ; and February 15, 2016 (English / French). Â As best I can tell from perusing the JUSTIN TRUDEAU, PRIME MINISTER OF CANADA website, there is no comparable statement for Manitoba’s Louis Riel Day this year on February 20. (The closest would seem to be “Statement by the Prime Minister of Canada on National Flag of Canada Day, Ottawa, Ontario, February 15, 2017.”) Just what any of this might mean I have no idea myself. But I think it is worth wondering about.

Two very last notes : First, the Winnipeg Centre NDP MP Pat Martin last introduced his private member’s bill “to reverse the conviction of Louis Riel for high treason and to formally recognize and commemorate his role in the advancement of the Canadian Confederation and the rights and interests of the Métis people and the people of Western Canada” in the 41st Parliament of Canada, 2nd Session, which ended in August 2015. It never became law but “Hope springs eternal in the human breast.”

Second, this coming June 15—17, 2017 the National Arts Centre Orchestra and the Canadian Opera Company will present performances of the 1967 opera Louis Riel at the National Arts Centre’s Southam Hall in Ottawa : “Sung in English, French, and Cree … The story of the polarizing Métis leader and Canada’s westward expansion is told in this landmark work. Composed by Harry Somers for our … centennial in 1967, this uniquely Canadian contribution to the opera world … will help mark the 150th anniversary of Canada’s Confederation.”

(3) 18th century ancestor – “The Conspiracy of Pontiac”

Chief Pontiac rouses supporters for his rebellion of 1763 – in defence of the old French and Indian Canada, at the end of the Seven Years War.

“Canada” is a First Nations / Aboriginal / Indigenous word (or, more exactly, Iroquoian it would seem). And it makes sense that its 19th century rebellions would have an 18th century First Nations ancestor – once known as the Conspiracy of Pontiac, now sometimes just called Pontiac’s Rebellion.

I have also recently been personally forced (so to speak) to come to grips with the legacy of Pontiac – War Chief of the Ottawa – in “Three 18th century wars that made two countries, 1754—1784 (May 15th, 2015). And for further information here I would just point to my esteemed colleague L. Frank Bunting’s long but remarkable June 2009 meditation on this website, called “There’s Pontiac .. then there’s Pontiac .. both worth a few historical tears.”

(4) Another late 20th century descendant : Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution Act, 1982

Quickly looking over what I wrote some four and a half years ago (well maybe four and a third?) in “175th anniversary of 1837 rebellions more important for Canadian democracy today than War of 1812” (Dec 4th, 2012), I came across this paragraph :

“One of the top four symbols and achievements in which pollsters have recently found that Canadians take pride is the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution Act 1982. And as the political scientist Frederick Vaughan urged a few years ago, the ‘Charter … is the closest Canadians have ever come to a document that affirms the rights of the people.’”

All four 19th century rebellions in Canada were similarly concerned to affirm the rights of the people in one sense or another. And at its best that is what populism of all and any varieties is concerned to do as well.

It may also be that the Pierre Trudeau who did so much to give us the Charter of Rights was, in some ways, almost as much of a populist as his son Justin Trudeau. And who knows? The two populists Preston Manning and Justin Trudeau today may have more in common than we think!

I think Canadian prairie populism in its principal forms was almost opposite to the hate-filled, resentful, backward-looking phenomenon that is being called “populism” nowadays — positive and forward-looking in its programmes and prepared to argue their merits on grounds of social and economic justice. The fact that its two manifestations seem to occupy opposite ends of the political spectrum as conventionally defined makes for me an excellent illustration of Stephen Leacock’s General Theory of Unsolved Riddles which bases its explanatory power on the prevalence of moral ambiguity, fragmentation, incompleteness and inconclusiveness.

I wonder what the counterweight, or alternative point of view, should be to the politicized, squashy and oh, so carefully balanced view of Canadian history that will flow through our airways and printways in the months ahead, with its measured doses of self-congratulation and self-flagellation. I am looking forward to the approaching CBC series, to see how they pull it off.

It’s also going to be fun to see what the current prime minister does in the next three weeks, if anything, to moderate the intense Vimyism that was the delight of his predecessor and will be expected by our veteranist fellow citizens. Perhaps as we honour the dead of the battle, WWI and other wars, as is most appropriate, we can take time to honour the dead of the transcontinental railroad, the Selkirk settlement, the emigrant ships, the early pioneering days of Upper Canada, our long string of epidemics, the famine in the Mackenzie Valley, the lumber industry, farming, and all the other unnatural deaths that have accompanied our long, majestic, riddle-infested march.

Stephen Leacock had an alternative point of view on “responsible government”. He thought that instead of the regional fiefdoms that were created under that policy, the British should have nurtured the development of a consolidated Empire Common Market. It’s interesting, and quite fruitless of course, to contemplate what would have happened if the world had evolved that way.