Democracy in the Dominions, 1948–1963

Apr 6th, 2018 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage NowDemocracy in the Dominions : A Comparative Study in Institutions was a 614-page university textbook by the Canadian Professor of Political Science Alexander Brady — first published in 1947, with a second edition in 1952 and a third in 1958.

By this point the dominions in question had been reduced to four : Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

The Irish Free State created as a British dominion in 1922 had given itself a new constitution in 1937, approved by 56% of the voters in a national plebiscite. This retained the Westminster parliamentary democracy established in 1922. But it replaced the ceremonial office of Governor General with a popularly elected ceremonial President, and affirmed that “all powers of government ‘derive, under God, from the people’.”

Exactly what this meant internationally was at first left somewhat vague. For more than a decade the “other governments of the British Commonwealth countries chose to continue to regard Ireland as a member of the British Commonwealth.” The Irish parliament’s Republic of Ireland Act which came into force on Easter Monday 1949 finally clarified that (Southern) Ireland was a parliamentary democratic republic, outside the Commonwealth of Nations.

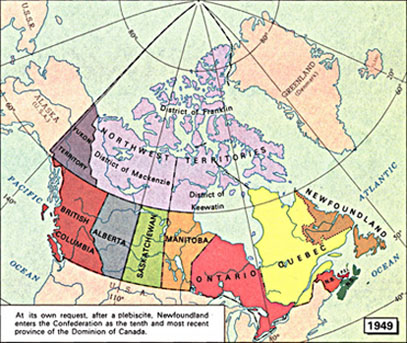

Meanwhile, the Dominion of Newfoundland had come to a practical end in the middle of the 1930s Great Depression. The United Kingdom, which had been effectively administering Newfoundland and Labrador through a Commission of Government since 1934, finally held two referendums on the future of “The Rock” in 1948.

Joey Smallwood, member of a “National Convention” that had been studying the issue since 1946, agitated for joining the 1867 Canadian confederation at last. This was one of three options in a popular referendum held on June 3, 1948. (The other two were keeping the UK Commission of Government or returning to independent responsible government.) No option won a majority. A second referendum on the two most popular options (independent responsible government or join Canada) was held on July 22, 1948. Joining Canada won 52.3% of the vote, and Newfoundland became Canada’s tenth province at midnight on March 31, 1949.

* * * *

It was a long stretch at best to call the Union of South Africa that had become a self-governing British dominion in 1910 a democracy.

In the late 1940s this was thinly veiled by not unrelated bad habits more subtly at work in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. But in the clearly worst case South Africa from the start had a black African (and “Coloured” and “Asian”) majority, and a white settler minority (Dutch or Afrikaner, and British). Although the original electoral franchise showed no explicit racial bias in one part of the new union, other “qualifications limited the suffrage of all citizens according to education and wealth.” And this effectively disenfranchised the great majority of non-white citizens.

The South African parliament had further eroded non-white voter rolls in all parts of the union, even after other qualifications on white male and female voters were removed in 1931. In his preface to the third edition of Democracy in the Dominions in 1958 Alexander Brady underlined “the democratic values and procedures that the European people of South Africa formally adopted for themselves but seem unwilling to share as partners with the coloured races.”

In his 1958 preface Brady also underlined “the extensive amendments introduced by the Nationalists to the constitutional system of South Africa between 1952 and 1956.” The tightening Apartheid regime of the Nationalist Hendrik Verwoerd led to South Africa’s transformation from a not-really-democratic British dominion into an openly white supremacist republic outside a changing Commonwealth of Nations in 1961. (And Nelson Mandela started his 27 long years in jail in 1962.)

Meanwhile, both India and Pakistan had become new self-governing dominions of an emerging new global commonwealth in 1947. India would soon graduate to a secular parliamentary democratic republic that replaced the British monarch with a ceremonial president as head of state, in 1950. Pakistan became what would prove a less stable Islamic republic in 1956.

Unlike Ireland, India and Pakistan remained in an evolving Commonwealth of Nations even after they became republics. The independence of the old British Raj after the Second World War nonetheless signalled the start of a fundamental reorganization (if not quite dismantling) of the empire on which the sun once never dared to set.

John Bowle’s Rise and Transformation of the British Empire would later explain that “when in 1949 a Conference of Commonwealth Prime Ministers accepted the Republic of India into the Commonwealth it took a radical decision.” Stanley de Smith, Professor of Public Law at the London School of Economics, summarized the impact of the decision in the 1960s : “Once the principle of republican membership of the Commonwealth had been conceded, the time had arrived for pronouncing obsequies over the doctrine of common allegiance.”

In 1953 an only recently crowned young Queen Elizabeth II was declared Head of the Commonwealth. Yet, as also urged by John Bowle, this had no practical constitutional meaning. And “for the Commonwealth, as such, the Crown had become entirely symbolic.”

* * * *

All four dominions in Alexander Brady’s book were founding members of the United Nations established at the end of the Second World War in 1945. For the long future vast changes were in the air. But Canada in the 1951 census was still quite “British” (and “French”).

By this point it was home to just over 14 million people. Just under 48% were reporting British and just under 31% French “origins.” Not quite 14% were various Other Europeans. A little more than 1% reported themselves as “Native Indian and Inuit (Eskimo),” about 0.5% “Asiatic,” and somewhat more than 0.1% “Negro.” (And you could still not claim “Canadian” origins in the Census of Canada.)

The Dominion Bureau of Statistics’ Canada Year Book for 1954 began with a colour photograph of “Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second on the day of Her coronation, June 2, 1953.” Keeping faith with the Incredible Canadian, however, the later text under “Constitution and Government” also stressed that : “Canada, under the Crown, has equality of status with the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth nations in both domestic and foreign affairs ; its government advises the Crown in the person of the Governor General on all matters relating to Canada.”

In 1947 Elizabeth II’s father George VI had issued new “Letters Patent Constituting the Office of Governor General of Canada” (also signed by “W. L. MACKENZIE KING, Prime Minister of Canada”). Under this dispensation the British monarch did “hereby authorize and empower Our Governor General, with the advice of Our Privy Council for Canada or of any members thereof or individually, as the case requires, to exercise all powers and authorities lawfully belonging to Us in respect of Canada.”

* * * *

On one related evolutionary path, in 1952 Canadian prime minister Louis St. Laurent appointed the Massey-Harris agricultural machinery heir Vincent Massey as “Canada’s first Canadian governor general” — or in the later words of the Winnipeg wit Larry Zolf “the first governor general who was not a British aristocrat and the last who looked like he was.”

(On another related path, in 1949 the Supreme Court of Canada had finally replaced the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom as the highest court of appeal in Canada.)

Not long before Vincent Massey became Governor General, Prime Minister St Laurent had also appointed him chair of a Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, in the spring of 1949. (A prominent other member of the Commission was Father Georges-Henri Lévesque from Laval University.) This was another response to the rapid rise of a cold-war American imperialism after 1945. In the words of Harold Innis (again), the new imperialism next door “has been made plausible and attractive in part by the insistence that it is not imperialistic.” And it inevitably threatened Mackenzie King’s Canadian nation-building legacy.

The Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences presented its final report on June 1, 1951. As explained by the Canadian Encyclopedia today, it “concluded that Canada faced ‘influences from across the border as pervasive as they are friendly,’ and warned against ‘the very present danger of permanent dependence’ on American culture.” It “advocated for the federal funding of a wide range of cultural activities,” including “the Canada Council for the Arts, federal aid for universities and the conservation of Canada’s historic places.” And this led to “the first major steps by the Canadian government to nurture, preserve and promote Canadian culture” (in both English and French).

On another related evolutionary path again : “In 1952, the first CBC and Radio-Canada television stations, CBLT-Toronto and CBFT-Montréal, began broadcasting. By 1955, CBC/Radio-Canada’s television services were available to 66 per cent of the Canadian population” (CBC/Radio-Canada, “Our History”).

Meanwhile, a certain degree of westward tilt in the Canadian economic geography bequeathed by the transcontinental fur trade had set in. A commemorative volume celebrating the 125th anniversary of the City of Toronto in 1959 included a contentious chapter on “The Economic Capital of Canada.” It told how “‘Toronto is America’s gateway to Canada,’ an editor from Montreal said this past winter. He thought that explained what was to him the unnatural pre-eminence of Toronto.”

* * * *

In sheer population numbers Canada’s historic metropolis in Montreal would remain larger than the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area until 1976. And a February 1947 “spewing geyser of oil at Leduc,” Alberta would soon enough bring further westward pressures to the confederation of 1867.

At the same time, while Halifax remained a crucial symbol for the Bank of Nova Scotia, the new de facto head office building the bank opened in Toronto in 1951 was a sign of growing financial muscle and economic clout in Canada’s then still second largest big city.

At the same time again, like almost everything else, all five largest Census Metropolitan Areas grew between 1951 and 1961 : Montreal from 1.54 million people to 2.22 million ; Toronto from 1.26 million to 1.92 million ; Vancouver from 586,000 to 827,000 ; Winnipeg from 357,000 to 479,000 ; and the Ottawa capital area from 312,000 to 457,000.

It was similarly a strength of Alexander Brady’s treatment of Canada in Democracy in the Dominions that it began with a chapter on “Regions and Nation.” This spelled out how: “Regionalism, the offspring of a continental state, profoundly influences the workings of Canadian democracy, and is reflected in the five main regions or sections, the Atlantic Provinces, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairie Provinces, and British Columbia.” When Robert Bothwell, Ian Drummond, and John English first published their commanding history of Canada Since 1945 in 1981 their related subtitle was Power, Politics, and Provincialism.

The rise and fall of Uncle Louis

(and last days of C.D. Howe)

Louis St. Laurent, a fluently bilingual Quebec lawyer with a French Canadian father and an Irish Canadian mother, had become Mackenzie King’s trusted Quebec lieutenant after the death of Ernest Lapointe in 1941.

Following a Liberal tradition of alternating anglophones and francophones, he was also “King’s chosen successor” as party leader, “a selection ratified by a … convention” in Ottawa in August 1948. As newly elected Liberal leader, St. Laurent was finally sworn in to replace Mackenzie King as Prime Minister of Canada on November 15, 1948.

According to a Canadian Encyclopedia article originally written by Robert Bothwell, St. Laurent “headed a cabinet of exceptional competence, including Lester Pearson in external affairs, C.D. Howe in trade and commerce, Douglas Abbott in finance and Brooke Claxton in national defence.” The exceptionally competent cabinet carried on with the gradual enlargement of the modest beginnings for a federal side to the 20th century welfare state, very gradually put in place by Mackenzie King — and the gradual extension of King’s parallel nation-building legacy.

As one part of its new national responsibilities, “Canada garrisoned troops in Europe under NATO [the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, established in 1949] and sent forces to fight for the UN [United Nations] in Korea” (1950–1953 : Canada sent more than 25,000 troops to the Korean peninsula, and more than 500 Canadians died in the conflict between North and South Korea). On a domestic nation-building front, federal equalization payments to help less wealthy provinces deliver some common national standard of public services — as first recommended by the Rowell-Sirois Commission in 1940 — started on the ground at last in 1957.

* * * *

Federal Liberal party strategists dubbed the silver-haired St. Laurent “Uncle Louis” for popular consumption. And for a time the act worked very well.

In the federal election of June 27, 1949 Uncle Louis’s Liberals won 191 of 262 seats in the Canadian House of Commons with just under 50% of the Canada-wide popular vote — to that point the greatest federal majority since 1867. They faced a mere 41 “Progressive Conservatives” led by George Drew, former premier of Ontario, 13 CCF members (mostly from Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and BC) led by M.J. Coldwell, and 10 Social Credit members (all from Alberta) led by Solon Low.

Uncle Louis’s Liberals did not do quite as well in the federal election held on August 10, 1953. But they still won 169 of 265 seats in the House (or 64% of the total) with just under 49% of the popular vote. Drew’s Conservatives took a somewhat more respectable 51 seats. Coldwell’s CCF had 23 seats (11 from Saskatchewan) and Low’s Social Credit 15 (four from BC and only 11 from Alberta).

Meanwhile, the once dominant Canadian age of the North American family farm was fading fast. Less than 35% of Canada’s population had been “urban” in 1901 (living in “densely settled built-up” areas, often linked to large cities). In 1951 63% were urban, rising to 70% in 1961.

By the 1950s as well many earlier economic hazards for individuals and families “were alleviated by family allowances, unemployment insurance, and above all a booming economy.” In pursuit of “a family, a home, a little land” Canadians fled to “the suburbs … Outside every Canadian city vast muddy tracts sprouted monotonous rows of houses.” Old rural areas adjusted to “an invasion of people who now expected running water and sewer lines as well as schools and roads” (Desmond Morton).

Meanwhile again, as explained on the “Official Web Site of the Nobel Prize” today : “In 1956, Great Britain, France and Israel launched an attack on Egypt aimed at removing President Nasser. The United States had not been informed, and the Soviet Union threatened to use atomic weapons against the assailants. The ‘Suez Crisis’ found its solution when the Canadian Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester Pearson, who had served as President of the United Nations General Assembly in 1952, won support for sending a United Nations Emergency Force to the region to separate the warring parties. This gained him the Peace Prize for 1957.”

* * * *

Lester Pearson’s Nobel Peace Prize made at least some Canadians proud, and gave a perhaps similar assortment an attachment to United Nations “peacekeeping” after the Second World War. By 1955, however, the federal Liberals had been in office for 20 consecutive years, and for 40 of the 55 years (73%) since the start of the 20th century. They increasingly saw themselves as “the natural governing party of Canada,” and (critics might say) it was going to their collective heads.

One part of the problem had been somewhat jocularly flagged by Harold Innis in the spring of 1948, a few months before the convention that ratified Louis St. Laurent as Mackenzie King’s chosen successor.

“As evidence of the futility of political discussion in Canada,” Innis told an academic audience in the United Kingdom, “there were Liberals who deplored the activities of the federal administration in no uncertain terms but always concluded with what was to them an unanswerable argument — ‘What is the alternative?’ In one’s weaker moments the answer does appear conclusive, but what a comment on political life …”

Another part of the problem was just Uncle Louis’s age, health, and waning enthusiasm for a demanding job. Early in 1954 (several months after leading his party to a 36-seat majority in the 1953 election) the prime minister had discussed his longer future with his “Minister of Everything,” C.D. Howe. As told in the appropriately masterful 1979 biography of Howe by Robert Bothwell and William Kilbourn : “St. Laurent had several times considered retiring. Each time he held back, convinced that his duty bound him to stick by his party, whose most conspicuous asset he was. But he was now seventy-two. After two great victories surely he had done enough for the party. Howe agreed. It would soon be time to go …”

Yet the time would not ultimately arrive for more than three more years. Meanwhile, trouble was growing around C.D. Howe himself, the US-born Massachusetts Institute of Technology businessman who became a British subject resident in Canada in 1913, and went on to dazzle Ottawa as a man who got things done in Liberal cabinets, from 1935 to 1957.

The leading issue around which the downfall of C.D. Howe and the Liberal party took place — the construction of a Trans-Canada pipeline to bring gas from western Canadian oilfields to eastern Canadian markets — was one on which Howe’s substantive position (to just get the pipeline built, in the face of vast obstacles in almost every direction) was at least on the side of the Canadian nation-building angels.

Even his friends, however, did not claim much for Howe’s diplomatic instincts and retail political skills. He could be arrogant and impatient. There was much narrow, self-interested opposition to his last great infrastructure project of a Trans-Canada pipeline. The arrogant and impatient C.D. Howe (now Minister of Trade and Commerce and Minister of Defence Production) became “the Tories’ biggest asset in Parliament,” according to his Suez-crisis cabinet colleague Lester Pearson.

The broader Canadian-American economic development background to the pipeline issue also stirred divisions inside the natural governing party, between C.D. Howe “business Liberals” and rising Canadian “economic nationalist Liberals” clustered around Walter Gordon from Toronto. And Gordon finally chaired a Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects (which worried about growing foreign and especially US ownership of the Canadian economy), from 1955 to 1957.

In the end Uncle Louis ran as Liberal leader one last time, in the federal election of June 10, 1957. And even at this point his Liberals managed a greater share of the popular vote than any other party (40.5%).

Yet the Progressive Conservatives under their new leader, John Diefenbaker from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, won 112 seats — seven more than the Liberals — with only 38.5% of the cross-Canada popular vote. There was some talk that the St. Laurent Liberals in 1957 could do the same as the King Liberals in 1925–26, and hang on to a minority government that looked to 25 CCF MPs for ongoing support. But the CCF was apparently not interested. And neither was the now 75-year-old Uncle Louis. He and his cabinet resigned on June 21, 1957, and John Diefenbaker formed the first non-Liberal government of Canada since 1935.

Renegade in Power

(And last prime minister of the old Dominion of Canada)

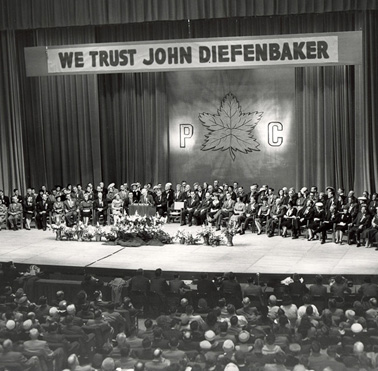

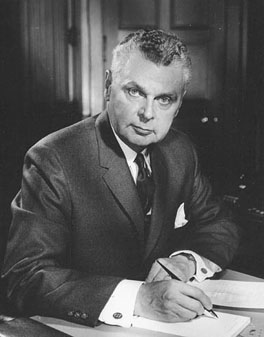

Peter C. Newman entitled his biography of the thirteenth prime minister of the 1867 confederation in Canada Renegade in power : the Diefenbaker years. (A half century on Allan Levine would write about the “defining Canadian political blockbuster, 50 years later.”)

In using the word “renegade” to describe Prime Minister Diefenbaker (aka “Dief the Chief” etc) Newman was adopting the jargon of the clubby old anglophone business establishment in central Canada (whose praises he would later sing in another book). The “Pipeline debate” finally focused on the month of May 1956 in the Canadian House of Commons. But in a broader sense it started in 1955 and carried on into the first half of 1957. And it ultimately grew into a populist revolt against elites too long in office. In the words of Wikpedia it was all about “the finances of the TransCanada pipeline, proper parliamentary procedure, and American economic influence on Canada.” In the first place it led “to the defeat of Louis St. Laurent at the polls in 1957.”

What happened next owed something to the domestic political miscalculations of the Nobel-Peace-Prize-winning Lester Pearson, in his very early days as new Liberal leader. He succeeded Louis St. Laurent at an Ottawa Coliseum convention in the middle of January 1958. A few days later he introduced a parliamentary resolution aggressively criticizing John G. Diefenbaker’s then only seven-month-old minority government, and proposing a motion of non-confidence in the new administration.

Liberal activist Walter Gordon later explained what followed in his mid-1970s memoirs : “This was just the opportunity Diefenbaker was looking for. In a long and devastating speech on February 1 he called the resolution arrogance and tore Pearson and the Liberal Party apart. He then announced that Parliament would be dissolved and a general election held on March 31 … The Conservatives under John Diefenbaker won 208 seats on March 31, 1958, the largest number of members ever elected by any political party in Canada’s history.”

The 208 “Progressive Conservative”seats across the country also included 50 of the 75 seats in Quebec — thanks in no small part to Premier Maurice Duplessis’s governing Union Nationale provincial political machine, concerned to “N’Isolons Pas Québec” (and no doubt to strike a francophone blow for conservative political philosophy in Ottawa as well).

Lester Pearson’s Liberals were similarly not the only party that withered in the Progressive Conservative populist storm. On March 31, 1958 Coldwell’s CCF won only 8 seats (only one of which was on the Prairies) — down from 25 in 1957, and Solon Low’s Social Credit won no seats at all. In his late 1960s analysis Murray Beck would point out that, for a moment in 1958 at any rate, John Diefenbaker’s “popularity far exceeded that of his party,” and he “was anything but an orthodox Conservative … Could he pursue a course that would satisfy the business and financial interests of central Canada — the backbone of the party — and still retain his new supporters from western Canada? … Did the results have even wider implications for Canadian politics in general? Dennis Wrong thought they might mean the emergence in Canada of what American analysts called ‘the nationalization of politics.’”

* * * *

By the early 1960s it was clear enough that 1958 would mark the peak of influence and popularity for Diefenbaker’s new populist Progressive Conservatism — and that, in various troublesome respects, the prime minister himself finally did prove to be a Renegade in Power.

At the same time, John George Diefenbaker, MP for Lake Centre and then for Mackenzie King’s sometime old seat of Prince Albert, in Saskatchewan, did win three consecutive federal elections as PC leader, in 1957, 1958, and 1962 . (Though in the first and last he could manage only minority governments.) There are at least two sides to his Canadian political legacy as well. In one he is the fading voice of a past that brings diminishing returns. In the other he speaks for the future, in a voice that will echo even after his death in 1979, while still serving as MP for Prince Albert, at the age of 83.

* * * *

Diefenbaker’s fading voice of the past could be reasonably enough summarized by calling him the last prime minister of the old first self-governing dominion of the British empire — or even just the last real prime minister of the old Dominion of Canada, that began to vanish in the real world of the 1960s.

The problem with this voice was (and still is, some will say) that, even by the 1950s, the old global empire was changing into something that could no longer fulfill the expectations of partisans like John Diefenbaker from Prince Albert (a city descended from a Presbyterian mission for Cree-speaking First Nations in what soon became the Northwest Territory of Canada, named to commemorate Queen Victoria’s beloved late husband).

Diefenbaker had a mother of Scottish and a father of German descent. Certainly in his own mind, his non-British surname gave his Canadian imperial faith a kind of principled purity that those who leaned towards the empire because of British ethnic and/or cultural origins lacked. But that was no protection against the changing political and economic structure of the global empire itself.

The Diefenbaker Conservative answer to the concern over increasing American economic influence in Canada, that figured in both the Pipeline Debate and the Liberals’ Gordon Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects, was to fall back on the old Imperial Preference in Canadian trade policy — and sell more to UK and other empire markets.

In this at least John Diefenbaker was not a renegade in power. And the strategy had made real sense in the early 20th century. In 1910, just before the “Our Lady of the Snows” election that brought Robert Borden’s Conservatives to office, some 50% of Canadian exports were going to the United Kingdom, and an additional 6% to other parts of the empire.

By 1950, however, only 15% of exports were going to the UK, and 6% to other parts of the empire/commonwealth. By 1965 only 14% were bound for the UK (and the other-commonwealth share was still 6%). Meanwhile, for many countries, the biggest market in the world was now in the rising giant of the USA (also for Canada conveniently next door).

Similarly, even for those Canadians who did favour the old empire because of “British” origins, times were quietly beginning to change.

The United Kingdom had remained the single largest source of migrants to Canada at large, from the 1820s to the middle of the 20th century. And there was a last British wave of this sort after the Second World War, induced in no small part by various federal and provincial government policies. But by the 1960s more diverse global migration trends were taking shape. The growing non-British immigrant population that had surfaced in Canada earlier in the 20th century was growing larger.

Finally, the changing British empire of the 1950s and 1960s had strategic implications for one crucial source of diversity in the original 1867 confederation, about which the “un-hyphenated Canadian” John G. Diefenbaker (again in keeping with some 20th century Conservative traditions) had scant understanding and even less sympathy.

Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessiss’s help in extending the 1958 landslide to la belle province could have opened a door to some return to the confederation’s founding Conservative age of Macdonald and Cartier. But John Diefenbaker was not the person to take advantage of the opportunity. There was a side to him that would later warm to a side of Pierre Trudeau. But it was not the side that actually spoke French.

* * * *

Diefenbaker had been born, in 1895, in Neustadt – a picturesque rural village in southwestern Ontario “with German roots.” His father was a teacher with “deep interests in history and politics,” who traveled in pursuit of improved employment. When John was eight years old the family moved to an old Hudson Bay Company post in what soon became the new Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Then in his mid-teens the Diefenbakers settled in the northern city of Saskatoon, where father William found more attractive work as a public servant.

After two other higher educational degrees, and some mildly controversial military service in the First World War, John Diefenbaker graduated from the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon with a law degree in 1919, in his mid 20s. His first law office was in a very small Saskatchewan town called Wakaw. But his practice prospered and by 1924 he had moved to the nearby city of Prince Albert. His political career as a somewhat unusual Conservative in a then largely Liberal province began a few years later. And he ran unsuccessfully against Mackenzie King for the Prince Albert seat in the 1926 federal election.

After a long period of persistent struggle in his political career (accompanied by rising success as a dramatic courtroom and sometime criminal lawyer), John Diefenbaker finally won the Saskatchewan federal seat of Lake Centre for the Conservatives in 1940. He held this seat until 1952 when it was abolished. Then he finally won Prince Albert (where he lived and worked) in 1953, and held it until his death in 1979. (Or as biographer Denis Smith has observed on the great turning point in 1940 : “After five successive electoral defeats, he would never suffer another.”)

Diefenbaker also ran twice for the federal Conservative leadership unsuccessfully, in 1942 and 1948, before finally winning (on the first ballot) in 1956. He had lived with the rise and fall of the Canadian prairie wheat economy up close, in a Saskatchewan that suffered enough from the 1930s Great Depression to elect Tommy Douglas’s provincial CCF party as the “first socialist government in North America” in 1944. Many of John Diefenbaker’s policy views fit better with the Progressive Conservative party that the former Progressive premier of Manitoba John Bracken had tried to create federally between 1943 and 1948, than with the party that former Ontario premier George Drew had led from 1948 to 1956.

In any case, the progressive side of Prime Minister Diefenbaker stands out clearly enough. In 1957 he appointed the first woman to a Canadian federal cabinet. Ellen Fairclough initially served as the somewhat ceremonial (and now defunct) Secretary of State for Canada. But she was soon promoted to Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, and then finished as Postmaster General in the Chief’s last cabinet. While at Citizenship and Immigration in 1962 she gave a major push to the growing liberalization and diversification of Canadian immigration policy.

In 1958 Diefenbaker appointed the first Indigenous member of the Senate of Canada — James Gladstone, a Cree adopted by the Blackfoot Confederacy, representing the province of Alberta. And partly at Senator Gladstone’s urging, in 1960 the Diefenbaker Conservatives used their vast parliamentary majority to finally give the vote in federal elections to all Indigenous adult citizens, including “status Indians” living on reserves.

Living (and making a living) in the troubled wheat economy of Saskatchewan during the 1930s gave Diefenbaker a particular sympathy for the struggles of provinces and regions in the midst of economic misfortune. He supported the federal-provincial equalization program at last introduced by the St. Laurent government. And in 1961 his Progressive Conservatives passed “the Agricultural Rehabilitation and Development Act [ARDA] … one of the first explicit attempts to create a national program for rural economic development.”

John Diefenbaker was also arguably the modern inventor of what the Canadian singer, rapper, and basketball impresario Drake would much later celebrate as “We the North.” In his opening campaign speech of the 1958 election Diefenbaker spoke of : “One Canada, wherein Canadians will have preserved to them the control of their own economic and political destiny. Sir John A. Macdonald … opened the West. He saw Canada from East to West. I see a new Canada — a Canada of the North.” In office he “undertook a massive northern infrastructure development program, which included airports, highways, and icebreakers.”

At the 1961 Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference John Diefenbaker’s Canada was also the only former member of Alexander Brady’s four democratic dominions of 1947 to oppose South Africa’s request for continuing Commonwealth membership as a republic, because of its now clearly defined apartheid policy of oppressing its Black majority. Diefenbaker stood with “Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Malaya’s Tunku Abdul Rahman, and the other non-white Commonwealth countries,” against “Britain’s Harold Macmillan … Australia’s Robert Menzies and Keith Holyoake of New Zealand.”

Finally, John Diefenbaker’s 1960 Canadian Bill of Rights was only an ordinary act of the federal Parliament. It did not apply to provincial governments and their powers, and it was not constitutionally entrenched. (It could be cancelled altogether by just another ordinary act of another federal Parliament.) It did set the stage, however, for Pierre Trudeau’s entrenched Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution Act, 1982. And it is arguably the Chief’s most forward-looking and even important legacy from the late 1950s and early 1960s.

* * * *

There was another, third side to John G. Diefenbaker from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, that had nothing to do with either the diminishing conservative past or the expanding progressive future. And, more than anything else, some would argue, this was what finally defeated his government soundly enough in the April 8, 1963 federal election.

The single most compelling and convincing ultimate study of the subject is probably the University of Western Ontario political scientist Denis Smith’s Rogue Tory: the life and legend of John G. Diefenbaker, first published long after the fact in 1995. And it seems most suitable to let Mr. Smith adumbrate the ultimate fate of Prime Minister Diefenbaker.

At the Chief’s funeral in 1979, Smith explains, the “new Conservative prime minister, Charles Joseph (Joe) Clark, delivered the graveside eulogy, describing Diefenbaker as ‘the great populist of Canadian politics . . . an indomitable man, born to a minority group, raised in a minority region, leader of a minority party, who went on to change the very nature of his country …’.”

If this seems somewhat too partisan and aggressively hagiographic, for a man who only served as prime minister for six years, Denis Smith’s own final conclusion is more temperate and realistic : “For writer George Bowering, Diefenbaker was the wittiest of all the country’s prime ministers, ‘and he was the most amazing campaigner anyone would ever see or hear.’ But [in the end, and all too soon] he got everyone — the Americans, the British, the Liberals, the economists, the Quebecers, and his own party establishment — mad at him.’”

Smith goes on : “By temperament Diefenbaker was never a team player. Once he was in office, it was quickly evident that he could not produce harmony in his cabinet, nor could he master the technical complexities of financial, defence, and foreign policies. He was overwhelmed by the problems of administration and was relieved by the prospect of escape into the House of Commons or onto the hustings, where his talents as a populist preacher could be exuberantly exercised. There, he was melodramatic and overbearing, appealingly comical, whimsical, and sarcastic. He put on a great show.”

Something of the show may linger on, even today. And John Diefenbaker arguably had more of at least one kind of influence on the long-term Canadian destiny after his time as prime minister, in the later 1960s and 1970s. He may nonetheless also remain most influential (and interesting) in his role as the last seriously committed prime minister of the old British Dominion of Canada. (Whose official demise would finally be most memorably signaled by the change in the name of the Dominion Bureau of Statistics to Statistics Canada, in 1971.)

From

Children of the Global Village :

Democracy in Canada Since 1497

Randall White

eastendbooks 2024

(For background on the larger work-in-progress of which this is a part, see The Long Journey to a Canadian Republic.)