RIP V.S. Naipaul – who thought briefly about moving to Canada long ago but then went back to England

Aug 24th, 2018 | By Randall White | Category: Entertainment

I have no deep familiarity with the writing of V.S. Naipaul, who “died at his home in London” Saturday, August 11, 2018, just a few days short of his 86th birthday.

But he is at least one of only a few great literary talents I for a while found fascinating after my mid-30s. I feel an urge to say something at the time of his death. (And why not? As explained on Twitter : “We are all journalists now.”)

I was late coming to Naipaul’s work. I first learned about him on Dick Cavett’s PBS series, during the age of “the last great intellectual talk-show host” on US TV.

Based on records now online, that was in late November 1980. And I was fascinated (refreshed even) by the man talking to Dick Cavett.

Not long after, I received Naipaul’s 1979 novel about modern Africa, A Bend in the River, as a birthday gift. Reading that led me to buy his early 1981 collection of four gripping non-fiction pieces, published in paperback by Vintage Books in New York as The Return of Eva Peron.

The next Naipaul book I bought (in hardcover this time) was his mid-1970s report on India : A Wounded Civilization. (He was born and raised on the Caribbean island of Trinidad – a grandchild of reputedly high-caste migrants from India.)

Sometime later I was lucky to come across a remaindered hardcover copy of Naipaul’s 1984 collection of two brilliant non-fiction pieces, Finding the Center. (The first piece pursues his own autobiography, and the second his travels in West Africa.)

Over the past few days I’ve been pleased to (re)discover that Ian Buruma (a great literary talent in his own right) considers both A Bend in the River and Finding the Center “masterpieces.”

Finding the Center is also Buruma’s personal favourite, among Naipaul’s “more than 30 books in a distinguished writing career spanning five decades.”

After Finding the Center I bought three more books by V.S. Naipaul myself.

A Turn in the South, published in 1989, describes his 1980s travels in the most angular geographic region of the USA today (and long ago as well).

Beyond Belief : Islamic Excursions Among the Converted Peoples was published in 1998. It draws on Naipaul’s travels in the Muslim countries of Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, and Pakistan.

Finally, I also managed to find a remaindered hardcover copy of the 2004 novel, Magic Seeds. It reports on adventures in India, Berlin, and London, and “Britain’s new multi-racial identity.”

More generally, all three of these later Naipaul books that still sit on my shelves deal with subjects that are still interesting and important in the turbulent global village today. But I have not found them as gripping as the first four of his books I read, in the first half of the 1980s.

There is nonetheless (I have just agreeably rediscovered) an eighth and final Naipaul item on my shelves today. And it has proved especially helpful in my personal homage to the many reasons to admire the body of his writing, now at the time of his death.

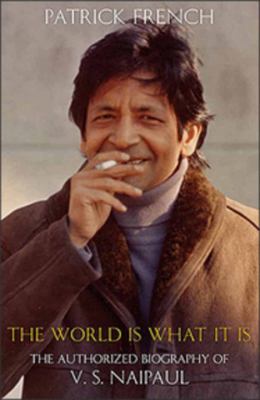

It is a neatly folded 7-page “hard” copy of Ian Buruma’s late 2008 review of Patrick French’s The World Is What It Is : The Authorized Biography of V.S. Naipaul.

It also fits well enough with Buruma’s August 13, 2018 eulogy, “V.S. Naipaul, Poet of the Displaced.”

Both pieces are from the New York Review of Books. The last paragraph of Buruma’s (online NYR Daily) eulogy a week or so ago is worth quoting in full up front :

“There is no such thing as a whole civilization. But some of Naipaul’s greatest literature came out of his yearning for it. Although he may, at times, have associated this with England or India, his imaginary civilization was not tied to any nation. It was a literary idea, secular, enlightened, passed on through writing. That is where he made his home, and that is where, in his books, he will live on.”

Beginnings

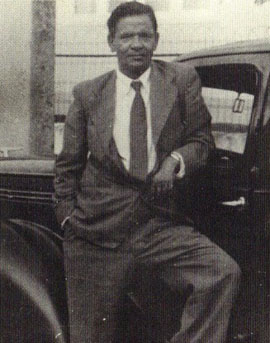

“Seepersad Naipaul, father of V. S. Naipaul, and the inspiration for the protagonist of the novel, Mr Biswas, with his Ford Prefect.”

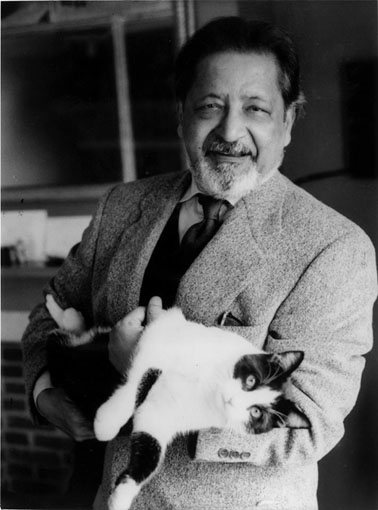

Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul TC, to give his final full official name and title, inherited his writing ambitions from his Trinidad journalist father, Seepersad Naipaul.

“Vidia” Naipaul (to his very best friends) graduated from Queen’s Royal College in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, when he was 18, and then won a Trinidad government scholarship to study at Oxford in England.

Naipaul graduated from Oxford in 1953, moved to London in 1954, and married his former Oxford fellow student Pat Hale in 1955. His first novel, The Mystic Masseur, was published in 1957, and won the John Llewllyn Rhys Prize. His break-out novel of literary greatness, A House for Mr Biswas (based on childhood memories of Trinidad) appeared in 1961.

Naipaul’s early literary success in London was not matched by immediate social and economic success. As also explained by his current Wikipedia article : “He had been especially unhappy with the increasing public animosity, in the mid-1960s, towards Asian immigrants from Britain’s ex-colonies … he and Pat sold their house in London.” In the late 1960s, “they travelled to Trinidad and Canada with a view to finding a location in which to settle.” They apparently did not find anything suitable in either place, and returned to England.

Right-wing politics?

Early on in his career in England, in the late 1950s, Naipaul had been befriended by the High Tory novelist (and earlier friend of the democratic Socialist George Orwell) Anthony Powell.

Somewhat later he “was introduced to” the popular historian “Antonia Fraser, at the time the wife of conservative politician Hugh Fraser.” She “introduced Naipaul to her social circle of upper-class British politicians, writers, and performing artists.”

By the time his novel In a Free State won the Booker Prize in 1971 (then worth the then substantial sum of £21,000) his social and economic fortunes were improving.

The trend continued. When Mel Gussow at the New York Times visited in 1994 he found Naipaul “and his wife, Patricia, have a home in Wiltshire, deep in England’s West Country … a comfortable house with modern furnishings.” There was as well a “wide lawn and garden” which “borders a meandering stream and looks out on a Constable-like landscape. The Naipauls also have an airy duplex in Chelsea, which they use when they are in London.”

Even when I first encountered V.S. Naipaul on Dick Cavett’s US TV show in 1980, it was clear enough that part of his act was at least seeming to say old-school white guy things, that a person who was not a coloured old British empire colonial could not get away with.

As Ian Buruma explained in his 2018 eulogy a week or so ago : “It is tempting to see Naipaul as a blimpish figure, aping the manners of British bigots; or as a fussy Brahmin, unwilling to eat from the same plates as lower castes.”

Yet views of this sort, Buruma went on : “miss the mark. Naipaul’s fastidiousness had more to do with what he called the ‘raw nerves’ of a displaced colonial, a man born in a provincial outpost of empire, who had struggled against the indignities of racial prejudice to make his mark … These raw nerves did not make him into an apologist for empire, let alone for the horrors inflicted by white Europeans. On the contrary, he blamed the abject state of so many former colonies on imperial conquest.”

Mr. Buruma had further explained in his 2008 review of Patrick French’s authorized biography that “bitterness about the way black politicians in Trinidad went after the Indian minority in the 1950s certainly affected Naipaul’s views.” But he is finally “too complex a figure to be dismissed as a racist. For in fact he has written about Africans, as well as Asians, with more intimacy and sympathy than many hand-ringing leftists who take a more abstract view of humanity?”

A twisted sex life, etc ?

The late Christopher Hitchens reviewed Patrick French’s “astonishing (and astonishingly authorized) biography” of V.S. Naipaul, when it appeared in 2008.

Hitchens noted that the book’s reception “has already focused very considerably on the ways in which Naipaul maltreated his wife, not only through his extensive resort to the services of prostitutes and his long-running affair with another woman, but through what might be called a sustained assault on her self-respect.”

Ian Buruma’s 2008 review of the French biography covers similar ground. And see as well Geoffrey Levy at Daily Mail.com in January 2009 on “Misogyny, mistresses and sadism: Why Nobel prize winning author VS Naipaul is at the centre of the most vicious literary war of the decade.” (This also covers Naipaul’s quarrel with his younger fellow writer, Paul Theroux.)

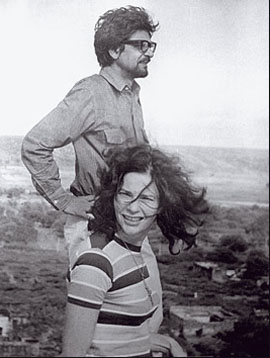

The quick details are that V.S. Naipaul married Patricia Ann Hale in 1955. The story from here is told succinctly (if not completely accurately?) in the author’s Wikpedia article : “During his first trip to Argentina, in 1972, Naipaul met and entered into an affair with Margaret Murray Gooding, a married Anglo-Argentine mother of three. [Other sources just say Margaret Murray, mother of two.] He revealed his affair to his wife one year after it began, telling her that he had never been sexually satisfied in their relationship. He moved between both women for the next 24 years.”

The Wikipedia article carries on : “In 1995, as he was traveling through Indonesia with Gooding, his wife Patricia was hospitalized with cancer. She died the following year. Within two months of her death, Naipaul ended his affair with Gooding and married Nadira Alvi, a divorced Pakistani journalist more than 20 years his junior. He had met her at the home of the American consul-general in Lahore. In 2003, he adopted Nadira’s daughter, Maleeha, who was then 25.”

Describing the relationship between Naipaul and Margaret Murray, Geoffrey Levy’s 2009 article notes “‘their’ taste for sado-masochism … Cursed by lifelong doubts about his own sexual inadequacy, he finds that he is able with Margaret – an Anglo-Argentinian who left her husband and two children for him – to indulge in abusive practices that had always fascinated him … According to Naipaul, the more he abused her, the more she came back for more.”

Levy also notes that Ms Murray wrote a letter to the New York Review of Books, in response to Ian Buruma’s 2008 review of the French biography. And her concluding sentence was “Vidia says I didn’t mind the abuse. I certainly did mind.” Further communications on the relationship appeared in subsequent additional letters to the New York Review of Books, published in the February 12, 2009 issue.

Naipaul’s second wife, Nadira, was at his side when he died on August 11, 2018. She said in a statement : “He was a giant in all that he achieved and he died surrounded by those he loved having lived a life which was full of wonderful creativity and endeavour.”

Canada (and Trinidad) as a road not taken …

Naipaul was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1990, and he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001. Two final sides to his life and career have particularly intrigued me.

The first is a passage from the later pages of A Bend in the River, which pretty clearly describes his reactions to his late 1960s trip to Canada (where I have lived virtually all my life myself), “with a view to finding a location in which to settle.”

The passage reads : “I didn’t feel I could stay in that country. I felt the place was a hoax. They thought they were part of the West, but really they had become like the rest of us who had run to them for safety. They were like people far away, living on other people’s land and off other people’s brains, and that was all they thought they should do. That was why they were so bored and dull. I thought I would die if I stayed among them.”

As a Canadian who has no other possible real identity I of course react against this assessment. And I think it is just one of several ways in which V.S. Naipaul’s perceptions of the world today were provocative but not finally exactly on the money.

At the same time, especially in the late 1960s (and early 1970s and even today still) the Canada I knew was in some very real ways a place that deserved the harsh summary Naipaul quietly offered towards the end of A Bend in the River. We needed and still need to improve.

At the same time again, I’d nowadays note as well that at some points the frequently abrasive and in later years curmudgeonly V.S. Naipaul had harsh things to say about almost everyone and everything.

And that included the England he and his first wife finally went back to after their unsuccessful quest for alternatives in Trinidad and Canada.

Ian Buruma noted in his 2008 review of the Patrick French biography that in a 1980 interview Naipaul declared : “In England people are very proud of being very stupid. A great price is being paid here for the cult of stupidity and idleness … Living here has been a kind of castration, really.”

Later sympathies for the BJP in India (& what about Brexit or even Donald Trump?)

The particularly intriguing side of V.S. Naipaul’s life and career I’m drawn to conclude on echoes the Right-wing politics? theme, and finally brings it right up to date in the USA today.

The particularly intriguing side of V.S. Naipaul’s life and career I’m drawn to conclude on echoes the Right-wing politics? theme, and finally brings it right up to date in the USA today.

To start with, as much as he belittled its taste for stupidity (and enjoyed travelling literally around the world ), England is where Naipaul ultimately chose to live for virtually his entire adult life. His English countryside idyll in his Wiltshire cottage may also remind the politically sensitive that “Wiltshire and Swindon vote[d] to leave EU” in the 2016 Brexit referendum. (And the county of Wiltshire gave all seven of its seats to Conservatives in the 2017 UK election.)

In his later years Naipaul also acquired something of an interest in the Hindu nationalist revival which boosted the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), that Narendra Modi finally brought to power in the 2014 Indian election.

Patrick French alluded to all this in a 2003 interview in India, while researching his Naipaul biography. Naipaul had, French suggested in response to a question, “said things which can be used in certain ways. People try to say, oh, he’s lined up with the BJP. I’m not trying to defend or condemn. I personally don’t share his position on a lot of subjects to do with India. But to see him as a mouthpiece for the BJP as he’s being presented sometimes I just don’t think is right … He goes somewhere, he studies the history, the society, the culture, he forms a certain point of view, and he expresses that view in very forceful terms. But it’s not because he is an ideologue.”

All this can take on a still sharper edge if you see Narendra Modi in India as a too much unexamined pioneer of the international right-wing populist surge that finally brought Donald Trump to the White House (which he may or may not now be occupying a little more precariously since this week of August 20-26, 2018 began).

To summarize the argument I have turned to the penultimate paragraph of the Naipaul eulogy offered by Rakesh Bedi on the Indian website firstpost.com, this past August 13, 2018 :

“The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it, Naipaul wrote. Barack Obama, in an interview to Michiko Kakutani as his presidency was winding down, found Naipaul’s vision very bleak and pessimistic. But the election of Donald Trump proves Naipaul right. The Democrats allowed themselves to be nothing and found no place in the White House. Naipaul had cannily dissected Republican pieties and foibles in his book on the Deep South. Walking across the Mason-Dixon line in A Turn in the South, Naipaul had written sharply about race and religion and their many conflicts and contradictions. And he had praised, something rare for Naipaul, James Baldwin, the black writer whose work is now being reread widely as America again grapples with its racial gladiators.”

(And in the interests of the deepest truth, I should make clear as well that I very finally agree myself with Barack Obama’s ultimate assessment of Naipaul’s vision. And it is Obama, I think, among all the democratic politicians in my lifetime, who has come closest to at least understanding the elusive [and necessarily multicultural?] “whole civilization,” for which the altogether brilliant English-language writer of the late 20th century Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul is said to have yearned.)