The Palace Letters in Australia 1975 – a big boost for the republican cause down under in 2020 (and in Canada too)!

Jul 15th, 2020 | By Greg Barns | Category: Key Current Issues

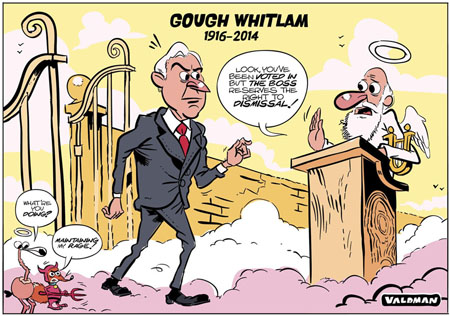

SPECIAL FROM GREG BARNS. HOBART, MELBOURNE, BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA, 14 JULY 2020. The 11th of November 1975 is a date etched into the collective mind of the Australian body politic. It was the day that the Queen’s representative, Governor General John Kerr, dismissed the elected Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, and commissioned Opposition Leader Malcolm Fraser to form a caretaker government. Mr Fraser’s centre right Liberal-National Party coalition government went on to record a thumping victory in a general election a few weeks later and remained in office until 1983.

And now in July 2020, after a four year battle for historian Jenny Hocking, which went all the way to the High Court (equivalent to Canada’s Supreme Court), Australia’s National Archives has this week unlocked 1975 correspondence between Kerr and Buckingham Palace. What it reveals is that while the Queen was not informed by Kerr he was going to sack Whitlam, she and her Private Secretary Martin Charteris overstepped the mark in encouraging Kerr and implicitly approving Kerr’s actions which were based in part on his fear Whitlam would sack him first.

For Australians and Canadians the Palace Letters, as they are being called in the media here, amply demonstrate the lack of independence each nation labours under by refusing to cut the apron strings to London.

The sacking of the Whitlam government occurred because the opposition parties had determined to block Supply in the Senate. Unlike its Canadian counterpart in Australia the Senate is a fully elected chamber and it has the power under the Australian constitution to reject a government’s budget. Whitlam and the Australian Labor Party (ALP) he led, had been elected in 1972 after 23 years of conservative government. Like his Canadian counterpart Pierre Trudeau, Whitlam was a well educated and erudite politician who wasted no time in embarking on a large-scale reform program that included introducing government health care, no fault divorce laws, a more independent foreign policy, and greater control over Australia’s vast mineral and energy resources. By mid 1975 his government had been battered by the world oil crisis and rampaging inflation. Senior ministers were forced to resign after they sought petro dollar loans through a shady middle man called Tirith Khemlani. By September that year the newly appointed and politically ruthless Opposition Leader Malcolm Fraser determined to force Whitlam to an election, two years before it was due. Fraser’s tactic was simple. The conservative parties, that had a majority in the Senate, would block the Supply Bills which grant authorisation for the government’s budget spending.

Kerr as Governor General watched events unfolding closely, knowing that he might be asked to intervene to resolve the fast moving constitutional crisis. Whitlam had suggested holding an election for half the senate to resolve the impasse. The Palace Letters also reveal that Kerr, and Buckingham Palace were also of this view, could enact the Supply Bills into law, bypassing the Senate. Whitlam, a formidable lawyer before entering parliament in 1955, would not sanction such an action arguing it was unconstitutional. Kerr turned to the Chief Justice of Australia Garfield Barwick who had been a minister in the conservative government during the 1960s and who was known to be hostile to the Whitlam government. The issue was whether what are termed the “reserve powers” of the Queen’s representative, to sack a government that cannot command supply, could be invoked.

What the Palace Letters reveal is the extent to which the Queen and Private Secretary Charteris were involved in the events happening 20,000 kilometres away. But first, consider this. The Queen and the Palace strongly opposed the release of the correspondence, which consists of 211 letters covering 1200 pages. As Jenny Hocking describes it : “The queen’s private secretary argued strongly against their release when the case began in the Federal Court, as did the governor-general’s official secretary, even claiming in letters included in a submission from the official secretary, Mark Fraser, that their continued secrecy was essential ‘to preserve the constitutional position of the Monarch and the Monarchy.’”

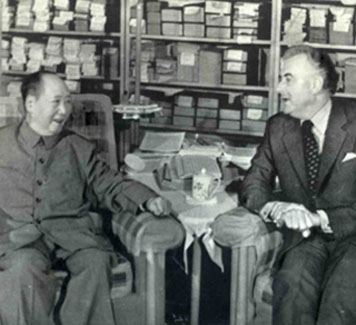

She and they might well have been so opposed. It is clear that the Queen and her advisers were giving Kerr comfort and advice. Malcolm Turnbull, himself Australia’s Prime Minister 2015-2018, and the former chair of the Australian Republican Movement, said the correspondence shows that the “governor-general was reporting to her [the Queen] almost like a local manager reporting to head office and seeking advice as to his options. Of course he made the final decision himself but he was getting a lot of advice on the way through.”

The Palace Letters reveal Kerr reporting to the Queen and Charteris on the views of the Australian media about the crisis. His conversations with Whitlam were also duly reported to London. And instead of Buckingham Palace asking Kerr to desist from seeking to involve the Queen in Australian political matters, they encouraged his conduct. Charteris was notably obsequious to the insecure Kerr writing seven days before the dismissal, “I think you are playing the vice-regal hand with skill and wisdom … The fact you have powers is recognised. But it’s also clear you will only use them in the last resort, and then only for constitutional – and not for political – reasons.”

On the issue of Kerr fearing Whitlam might sack him Charteris wrote on 2 October 1975 : “Prince Charles told me a good deal, and you’d spoken of the possibility of the Prime Minister advising the Queen to terminate your commission. At the end of the road, the Queen – as a constitutional sovereign – would have no option but to follow the advice of her Prime Minister.” In other words, Charteris was opining about an Australian domestic political matter and giving Kerr comfort. In fact as early as July 30, 1975 Charteris wrote to Kerr thanking him for sending “[t]hese fascinating accounts of what has been going on in Canberra,” which “have been read with great interest by The Queen. Indeed, Her Majesty’s interest in them has to some extent delayed this reply. She likes to read them at leisure.”

The monarchists in Australia are busy today defending the Queen and Buckingham Palace, because the Palace Letters reveal Kerr did not tell the Queen he was going to sack Whitlam. He did not tell her, he said, to protect the monarchy. But as Andrew Clark noted in the Financial Review today Charteris in a 4 November letter “told Kerr that the work of constitutional scholar Eugene Forsey supported the idea of dissolving Parliament, which is effectively what he secured by sacking Whitlam. An eminent Canadian constitutional expert on relations between the Crown and Commonwealth parliaments, Forsey believed it was ‘proper’ to grant a dissolution if supply was refused.”

The Palace Letters are of real relevance today for Commonwealth constitutional monarchies like Australia and Canada. They show the fundamental flaw in having a monarch in a foreign country with, at the end of the day, a role in the domestic political and democratic travails of supposedly independent nations. Why is it that Kerr had to contact Buckingham Palace in the first place? Because Australia, like Canada, is not fully independent while it has a deputy head of state in the form of the Governor General. And for a foreign head of state to interfere in the democratic process of Australia and Canada – and yes what Kerr did could happen in Canada : just ask the writings of the late Eugene Forsey – is surely intolerable to those who believe that Canadians and Australians are entitled to be masters of their own destiny.

The argument for an Australian or Canadian republic is demonstrably strengthened by the release of the Palace Letters.

Greg Barns SC is a barrister and author. He was Campaign Director for the 1999 Republic Referendum in Australia and Chair of the Australian Republican Movement from 2000-2002. He is, with Anna- Krawec-Wheaton, the author of An Australian Republic (Scribe Books 2006).

He currently works at Salamanca Chambers Hobart, Gorman Chambers Melbourne, and Higgins Chambers Brisbane.

John Kerr should have considered the options and then made a decision which he deemed best in accordance with Australia’s constitution.There was no reason to bring the Queen into it.