Looking at the old British dominion of Ireland and its new relevance for Canada after the death of Queen Elizabeth II

Nov 29th, 2022 | By Randall White | Category: In BriefONTARIO TONITE. RANDALL WHITE, FERNWOOD PARK, TORONTO, TUESDAY 29 NOVEMBER 2022. John Kerrigan, the Cambridge University literary scholar (and convener of the Cambridge Group for Irish Studies), has just published a more than 7000-word discussion of one movie (Kenneth Branagh’s “Belfast”) and 15 recent books about Ireland today, in the October 20, 2022 issue of the London Review of Books.

The long title of Kerrigan’s piece is “Turning Wolfe Tone: A Third Way for Ireland.” (Where Wolfe Tone was the late 18th century Protestant Irish republican who played a leading role in the failed Irish Rebellion of 1798 — a “major uprising against British rule in Ireland.”)

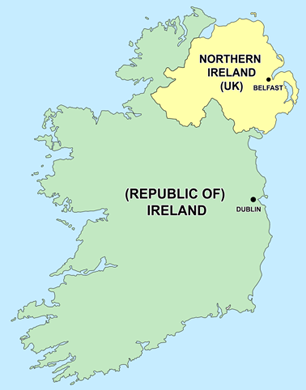

Fate of the Six Counties of Northern Ireland

As best as I can make out, the underlying political thrust of Kerrigan’s piece turns around the fate of the six counties of Northern Ireland, that for the time being remain yet another part of the more complex world of the 2020s United Kingdom (along with England, Scotland, and Wales).

What many among us outside the UK see as its current tragic mistake of taking Brexit seriously has brought this fate into fresh limelight. And this light flows from the knotty question of the border between the Northern Ireland that is still part of the United Kingdom, and the more southerly 26 counties of the modern Republic of Ireland that is still part of the European Union.

The ultimate political bottom line of John Kerrigan’s discussion of more broadly cultural books such as Seamus Deane’s Small World : Ireland 1798–2018 or Malcolm Sen’s A History of Irish Literature and the Environment clearly enough seems to be that the six (once especially Protestant) counties of the north will ultimately (and stress that word) join (or rejoin) the 26 (once especially Catholic) counties of the south, in an ultimately united Irish republic that covers the entire emerald isle.

As Kerrigan writes : “It did no harm to the [Kenneth Branagh] film’s reception that the insecurities induced by Covid were compounded in Northern Ireland by Brexit … loyalists were becoming agitated about the Northern Ireland Protocol. Nationalists and republicans also had a concern … (or … a hope) that … a full-on Brexit would have the contrary effect of pushing the six counties back towards the border infrastructure … Loyalism is now adrift and frustrated … The success of Sinn Féin in the May elections added fuel to the fire, while the death of Elizabeth II and the recent census result, showing a Catholic majority in the North … increase unease.”

The changing Republic of Ireland in the south (and west)

At the same time, Kerrigan notes, the traditional “stranglehold of Catholicism on Irish lives” in the republic of the south has been losing its grip as the new economic age of the”Celtic Tiger” has settled in, after the initial Irish boom years 1995–2007.

As “the editors of the Routledge International Handbook put it ‘the success of the 2015 Marriage Referendum made Ireland the first nation to support same-sex marriage by way of a popular vote, and a second referendum in 2018 … allowed for abortion on demand.’”

(Kerrigan notes as well that : “About one-eighth of the population of the Republic is now categorised as ‘non-Irish national’, a society as ethnically diverse as England …”)

Like Kenneth Branagh, John Kerrigan also has some sympathy for the current Northern Irish dilemma. The “ most subversive” side of Branagh’s “Belfast” is how it shows “working-class Protestants in a good light.” Kerrigan similarly writes : “We can still learn plenty from Deane about the problems of partition, and from his inadequate approach to them. The core of this inadequacy is a lack of empathy with the culture of Northern Irish Protestantism.”

Yet in the late fall of 2022, Kerrigan concludes : “With talk of a border poll now spreading and middle-class voters increasingly open to unification, Ulster Protestants are wondering about alternative futures … The old joke about the Irish question is that when Gladstone thought he’d answered it the Irish changed the question. The subtitle of Patterson’s book, ‘Will six into twenty-six ever go?’ is politically as unresolved as it is arithmetically impossible, but it has the virtue of asking the inhabitants of the island to answer the question for themselves. Ulster Protestants are familiar with the coercions that either force them into Irishness or invite them to leave, though of course they still have the option of turning into Wolfe Tone.”

(And embracing the tricolour flag of the Republic of Ireland, which already has green, white, and orange — the last of which may remind some very old and even a very few younger Ontario residents of the Protestant Orange Parades, that in an earlier era blossomed north of the North American Great Lakes, once also especially Loyal to the global British Empire.)

The Irish Free State 1922–1937 — “established as a dominion of the British Empire”

All this is quite intriguing, but it quietly passes by the political elements of Irish history in the 20th century that are most interesting for Ontario — and Canada — today in the 21st century.

As explained by Wikipedia, the legendary “Easter Rising” of 1916 “was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an independent Irish Republic while the United Kingdom was fighting the First World War. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798 and the first armed conflict of the Irish revolutionary period..”

The Easter Rising finally led to the “three-year Irish War of Independence [1919–1921] between the forces of the Irish Republic — the Irish Republican Army (IRA) — and British Crown forces.” And this finally led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921.

Within the 26 counties of the south this Treaty “provided for the establishment of the Irish Free State within a year as a self-governing dominion within the ‘community of nations known as the British Empire’, a status ‘the same as that of the Dominion of Canada’. It also provided [the six counties of] Northern Ireland, which had been created by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, an option to opt out of the Irish Free State, which the Parliament of Northern Ireland exercised.”

Not all those on the side of the Irish Republic from the three-year War of Independence supported the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which gave only Irish republicans in the south only the same status as the 1920s self-governing Dominion of Canada, with the British monarch as head of state, represented locally by a governor general appointed by the UK government. The “treaty was narrowly approved” by Irish republicans, and “the split led to the Irish Civil War, which was won by the pro-treaty side.”

One of the early key leaders on the pro-treaty side, Michael Collins, “justified his acceptance of the Treaty as giving Ireland ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’. It was, in other words, a half-way house, but was the most that could be got at that moment, given the impoverished and exhausted state of Ireland and the power of the British Empire. In the fullness of time, Collins predicted, complete freedom — a republic — would be attained. Once again, he was right.”

President of Ireland replaces Governor General of Free State in 1937

The crux of the modern Irish political achievement in realizing Michael Collins’s vision of the early 1920s was figuring how to turn the institutions of a self-governing British dominion into those of a completely free or independent republican parliamentary democracy on the so-called “Westminster model”, by turning the British monarch’s representative of governor general into an independent republican Irish ceremonial head of state, more or less above the partisan political fray.

In taking this crucial step — in two further parts in 1937 and then again in 1949 — the British dominion known as the Irish Free State was helped along its ultimate path by Canadian prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s struggle to make the governor general of a British dominion accountable to the dominion’s own government (in the person of the dominion prime minister!), rather than the British or imperial or UK government at Westminster on the River Thames.

This struggle began with the so-called King-Byng Crisis in the Canadian election of 1926, and ended with the formal marker of the UK Statute of Westminster in 1931.

From here, with the office of a dominion’s governor general newly accountable to the dominion government rather than the imperial government in London, it was a logical if no doubt radical enough innovation to make the office of governor general accountable to the dominion electorate, or the democratic people of the particular Westminster parliamentary democracy involved.

This is what the government of the Irish Free State did when it rewrote its 1922 constitution in 1937. Borrowing yet again from Wikipedia, the government “presented a draft of an entirely new Constitution” to the Irish Free State parliament (known in Irish as the Oireachtas). An “amended version of the draft document was subsequently approved” by parliament. And a popular “plebiscite was held on 1 July 1937, which was the same day as the 1937 general election, when a relatively narrow majority approved” the document (56.5%).

The new Constitution came into effect on 29 December 1937. In the words of Wikipedia again : “The state was named Ireland (Éire in the Irish language), and a new office of President of Ireland was instituted in place of the Governor-General of the Irish Free State.”

Office of Irish President and Canada today

The new president of Ireland had and still has essentially the same largely ceremonial powers as the old governor general. (The prime minister or in Irish the Taoiseach remains head of government and chief executive, and the most influential political office holder.)

In what also remains a comparatively radical gesture, however, the President of Ireland was (and still is) directly or popularly elected by the Irish people — albeit only by the people choosing among candidates nominated by either “At least 20 members of the Oireachtas” or parliament (of which there are currently 218 members) or “At least four county or city councils ” (where there are now 31).

In 1937 many observers argued that, even with such a tight nominating process, a directly or popularly elected ceremonial head of state could not long survive in a parliamentary democracy, without challenging the role of the prime minister and throwing the Westminster political system into some kind of chaos. Even today many argue that a directly elected ceremonial head of state as a replacement for the British monarch could not work in remaining so-called Commonwealth realms such as Canada.

Yet, whatever else, an institution of this sort has now survived and even prospered in Ireland for some 85 years, while leaving the essential operation of a Westminster parliamentary democracy with a prime minister as head of government quite intact. The current President of Ireland Michael Higgins is the ninth holder of the office since 1937!

One subtle further wrinkle in this history is that from 1937 to 1949 there remained some international ambiguity about the status of the President of Ireland. The British “Empire and Commonwealth” also held its last Imperial Conference of “British and dominion prime ministers” in 1937. And this was “the first Imperial Conference in which the Irish Free State chose not to participate … Nonetheless, the Irish Free State was still regarded as a Commonwealth member.”

In 1949 the government of the 26 counties in southern Ireland “explicitly became a republic under the terms of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948, definitively ending its tenuous membership of the British Commonwealth.”

In 1949 as well a Constituent Assembly of the former British dominion of India passed legislation under which it became a Westminster-style parliamentary democratic republic in 1950. But, with the agreement of other Commonwealth prime ministers in such places as Canada, India remained a republican member of a newly evolving Commonwealth of Nations.

India’s selection method for its ceremonial president replacing the former governor general was and still is somewhat different from Ireland’s. In this case the president is indirectly elected by federal and state parliaments or legislatures. And this may prove the preferred approach to politely and no doubt gradually waving goodbye to the British monarch as head of state in Canada, now that the long reign of the much-admired Queen Elizabeth II has ended.

The president of the Republic of Ireland nonetheless remains an intriguing alternate model, of particular appeal to more radical democrats concerned to underline the ultimate sovereignty of the Canadian people in what the Constitution Act, 1982 quietly alludes to as Canada’s present-day “free and democratic society.”