Brian Mulroney from Baie-Comeau : The last of the Progressive Conservatives?

Mar 6th, 2024 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In Brief

COUNTERWEIGHTS EDITORS, GANATSEKWYAGON, ON. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 6, 2024. Yesterday’s announcement of the state funeral for former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney (1984–1993) from present Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (2015–20??) is suitably couched in high-minded language :

“Brian Mulroney devoted his career to serving Canadians. He was an extraordinary statesman and distinguished politician, respected both here at home and around the world … To honour the legacy he leaves behind, a state funeral is being held in Montreal on March 23rd …”

Most of the almost ubiquitous other commentary we’ve seen has had a similar tone. And in this context we at least found online journalist Holly Doan’s posting of some much more unguarded Mulroney remarks on March 4 refreshing (or at least a more realistic change of pace).

The remarks were taken from Peter C. Newman’s controversial 2005 book on the “Secret Mulroney Tapes” (which Mr. Mulroney himself felt was a betrayal) : “Prime Minister Brian Mulroney: Ottawa is a ‘sick’ city that runs on ‘goddamned incest’: ‘They’re all married to one another. They’re shacked up with one another. Their wives are on the payroll of the CBC. It’s just awful.’”

There is no doubt some deeper truth in all this — which is of course why it’s interesting. (It’s also telling tales out of school, which is also why it’s interesting.) At the same time, it finally reminded us that we have a good enough and even somewhat more high-minded tribute to Brian Mulroney of our own, in the relevant pages of senior editor Randall White’s almost altogether completed work in progress, Children of the Global Village : Democracy in Canada Since 1497.

With respect and (as with so many others among us) some real admiration, here then are the first two sections on Canada’s 18th prime minister from Part IV, Chapter 2 of Dr. White’s draft Canadian political history book as it appears on this site. They start with a subtitle …

Postscript, 1982—1992 :

The last of the Progressive Conservatives?

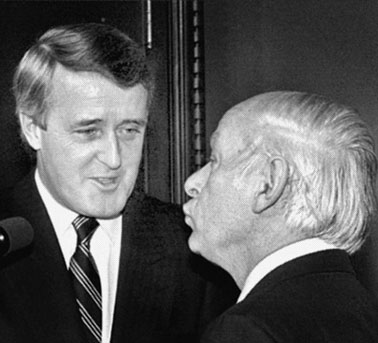

On June 11, 1983 — not quite 14 months after Elizabeth II had proclaimed the Constitution Act, 1982 in Ottawa — the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada did something unusually sensible and strategic.

At a convention in the federal capital it elected as leader a 44-year-old labour lawyer, negotiator, and political activist of Irish descent, who had grown up in a francophone and even sovereigntist region of Quebec, and was almost as flawlessly bilingual as the retiring Pierre Trudeau.

Brian Mulroney from Baie-Comeau (in a provincial electoral district now known as René-Lévesque) had (like others) failed his bar exams twice in the 1960s. His personal charm and negotiating skill nonetheless built a bustling Montreal legal career in the 1970s.

Mulroney did not hold elected office until just after he became PC leader in 1983. But he had worked in the fedeal Conservative Party since John Diefenbaker’s historic majority win in the 1958 election. He had a failed but instructive dry run as a candidate for the federal PC leadership in 1976. And : “He made telephone calls because he wanted to, because reaching out and talking was an essential part of his nature” (Bob Rae).

When he finally resigned as PC leader and Prime Minister of Canada in June 1993 Brian Mulroney and his party had become astoundingly unpopular. Under the leadership of his successor, Kim Campbell from Vancouver Centre, the Progressive Conservatives won only two seats (and a mere 16% of the Canada-wide popular vote) in the October 1993 federal election.

Yet in the 1984 election that brought them to office the Mulroney Conservatives had done almost as well as the Diefenbaker Conservatives in 1958. They won just under 75% of the seats in the House, with just over 50% of the popular vote. (In 1958 Diefenbaker’s party had won more than 78% of the seats with just under 54% of the vote.)

* * * *

Brian Mulroney had one great success in his career as Canadian prime minister, 1984–1993 — the ultimate achievement of a modern Canada-US (and then Canada-US-Mexico) free trade agreement. And he had one great failure — the defeat of his two efforts to win Quebec’s formal assent to the Constitution Act 1982, in the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords.

At the same time, though he got on famously with President Ronald Reagan in the United States (and then with President George H.W. Bush), Mulroney was more of a Diefenbaker Progressive Conservative than the kind of new right ideologue brought into the 1980s limelight by both Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom. (As spelled out, eg, in the political direct mail pioneer Richard Viguerie’s The New Right : We’re Ready To Lead, self-published in 1980 and 1981 in Falls Church, Virginia, USA, with an introduction by televangelist Jerry Falwell.)

Somewhere in between Mulroney’s one great success and one great failure, he also managed a few more modest but enduring and largely progressive accomplishments. The almost certainly most compelling example flowed from his stalwart support for ending the white supremacist apartheid regime in South Africa.

Even the South Africa that had figured in Alexander Brady’s Democracy in the Dominions in 1947 was still far from any seriously inclusive practical embrace of the country’s black African majority. But the rise of a more openly white supremacist, segregated regime can be dated to the at first shaky electoral victory of D.F.Malan’s Nationalist party in 1948. Malan’s successors would finally lock the African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela in jail in 1962. And in 1961 John Diefenbaker had already set Canada on the side of global diversity (and against the United Kingdom, Australian, and New Zealand governments of the day), with his support for apartheid South Africa’s leaving the new Commonwealth of Nations, into which the old British empire was rapidly dissolving.

Mulroney carried on and stiffened this Diefenbaker tradition with his aggressive support for the liberation of Mandela and the end of South African apartheid in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Many years later, in 2015, he was awarded the new South Africa’s Order of the Companions of O.R. Tambo in Gold, in recognition of his contribution. The explanatory text for the award summarizes this particular achievement :

“Brian Mulroney’s role in the fight against apartheid … contributed immensely to South Africa’s liberation struggle … From 1985, Mulroney spearheaded an aggressive Canadian push within the Commonwealth for sanctions to pressure the racist South African government to end apartheid and release Mandela from prison where he had been locked up for a quarter century … That put him [Mulroney] at odds with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher … After his release from prison in 1990, Mandela … ended apartheid as national leader … But in the 1980s, when he needed foreign friends the most, it was Mulroney’s Canadian Government that led the way. Mandela never forgot it.”

Brian Mulroney can claim credit as well for some pioneering Canadian federal interest in climate change and the environment. Future Green Party of Canada leader Elizabeth May served as senior policy advisor to Mulroney’s Minister of the Environment, Tom McMillan, 1986–88. She helped create several new national parks, and negotiate the Montréal Protocol, an international agreement on Earth’s ozone layer. The Mulroney government similarly passed an Environmental Protection Act in 1988, and negotiated an Acid Rain Accord with George H.W. Bush’s USA in 1991 — “an air quality agreement that has significantly reduced acid rain levels and sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions.”

In 1991 the Mulroney government also introduced an unpopular value-added sales tax called the Goods and Services Tax, that helped manage federal government finances without aggressively cutting popular public services. Prime Minister Mulroney was sometimes impressively non-partisan in his appointments as well. The most striking example may be his choice of former Ontario New Democratic Party leader Stephen Lewis (also the son of former federal NDP leader David Lewis) as Canadian ambassador to the United Nations, 1984–1988.

For more on each of PM Mulroney’s one great success and one great failure see the final sections of Randall White’s Children of the Global Village, Chapter 2 of PART IV : THE LONG JOURNEY TO A CANADIAN REPUBLIC, 1963—20?? — “New northern directions (and two lights that failed), 1976—1992.”