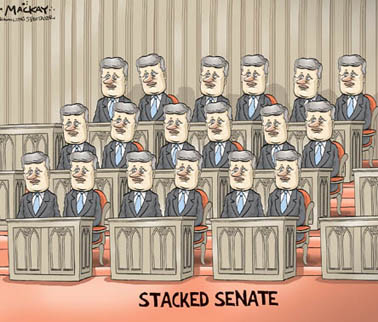

Who or what would reformed Senate of Canada represent is crucial question for Senate reformers now!

Mar 17th, 2013 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

Stockwell Day, back in the day – the new Conservative Party’s Justin Trudeau, in an earlier era (or not)?

Sometimes, when not much seems to be happening on the current political scene, you can catch glimpses of a more fascinating long-term future in the minor events of the day.

The headline on Andy Radia’s recent interview with the now retired Stockwell Day, in the wilds of BC, may qualify under this heading, despite all current scepticism in opposite directions : “Yahoo! Exclusive: A Liberal-NDP alliance is inevitable, Stockwell Day predicts.”

Another seemingly drab headline of today that just might qualify for a brighter long-term future, I think, is this past Friday’s “Senate reform could weaken minority language representation, rights groups say.” The long and short here is summarized in the article’s first sentence : “The country’s largest organization representing French-language communities across Canada fears current proposals for an elected Senate could harm representation for minority language rights, and is hoping the Supreme Court of Canada will hear their concerns.”

Marie-France Kenny, présidente de la Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne (FCFA) du Canada.

It is worth underlining, I think as well, that Marie-France Kenny, president of the Federation of Francophone and Acadian communities of Canada, is NOT arguing for abolition of the unreformed Senate of Canada we have today: “If we abolish the Senate, we lose representation of minorities … Having the counterweight of the Senate in terms of representation of Francophones makes sense.” And : “We’re not saying we’re against reforms per se, what we’re saying is that in any reforms we look at . . . we should ensure (fair) representation.”

I am someone who has been (almost insanely, I agree, it does often seem) interested in Canadian Senate reform, ever since writing a book on the subject almost a quarter of a century ago, at a publisher’s suggestion. And these recent comments from the Federation of Francophone and Acadian communities of Canada have struck a soft spot, in the armoured vests we Senate reformers have grown accustomed to wearing over the years, as a matter of safety first.

Senator Mike Duffy holds up his glass during the Maritime Energy Association's annual dinner in Halifax earlier this year. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Devaan Ingraham.

Marie-France Kenny, that is to say, does point to what has increasingly seemed to me a key current reality about the apparently insanely quixotic subject of reforming the unreformed Senate of Canada at last. No matter how many times Pamela Walin and/or Mike Duffy (or anyone else) may or may not make dubious expense claims, the debate on reform won’t even start to get serious, until we start talking seriously about just what representation in a reformed Senate ought to involve. It goes without saying (much more) that a reformed federal Senate has to be democratically elected, and that there have to be reasonable term limits for senators. The key question is just what or who should reformed senators be representing – that isn’t already taken account of by the principle of representation by population in the Canadian House of Commons?

Geography as a first principle

The main answer to this question that I have long been convinced by – as a self-confessed Senate reformer – is geography. Geographically vast democratic “federations” like Canada (or Australia or the United States or India, as opposed to geographically compact “unitary states” like France or England or Japan) need to have some adequate democratic representation for less populated stretches of important geography in their federal institutions – along with democratic representation by population (where every adult person gets one vote) .

It is for this reason that both the United States and Australia have important democratically elected Senates, and India has a parallel body known as the Rajya Sabha (as opposed to the Lok Sabha, comparable to the Canadian House of Commons).

During my earliest career as a Senate reformer I at least took very seriously the original modern Western Canadian demand (as it were, with special reference to the mid 1980s provincial government of Alberta) for a so-called “Triple E” Senate in Canada (elected, effective, and equal), modelled on the US and Australian experience. In this case each legal or regional sovereign unit in the federal system – states in Australia and the US, provinces in Canada – has equal representation in the federal Senate.

Subsequent experience and reflection, however, has persuaded me that “equal provincial representation” in a reformed Senate is an unworkable formula in the unique circumstances of Canada. And here, I think, two key Canadian peculiarities stand out. The first is the role of Quebec – which has never quite been “a province like the others,” as a result of its continuing francophone majority. (And this status has now been confirmed, one might reasonably enough argue, by the Canadian House of Commons’ late November 2006 recognition that the Quebecois constitute a nation within a united Canada!) The second is a somewhat unusually extreme tendency in Canada for population to be concentrated in a minority of “big”provinces.

Supplementary cultural representation formulas

To get right down to essentials without further adieu, for a number of years now I have been in favour of a reformed Senate of Canada representation formula that gives special representation to our country’s vast geography, while at the same time recognizing the unique circumstances of francophone Quebec, and the unusual concentration of population in the largest provinces.

This gives (in my particular twisted vision at any rate) a provincial allocation of elected or reformed Senate of Canada seats as follows: Quebec — 12; British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario — 6 each ; all other provinces — 3 each ; and three territories — 1 each.

From the blog “Buckdog – Fresh Winds From The Prairies,” in a Thursday, August 27, 2009 article entitled “Harper Names Nine New Tory Porkers To Senate.”

Pondering the current arguments being presented to the Supreme Court of Canada by Marie-France Kenny, president of the Federation of Francophone and Acadian communities of Canada, and others like her, I have remembered that I earlier also wanted to accommodate minority cultural, as it were, as well as majority geographic interests in any reformed Senate scheme of representation.

Without getting into a lot more detail at this juncture, I want to add two strands of what might be called minority cultural as well majority geographic representation to my own list of key current representation formulas. The first is an additional three-member delegation representing officially linguistic minorities – say two senators for francophone Canadians outside Quebec and one senator for anglophones inside Quebec?

Nalini Sharma and Mika Midolo at cp24 TV in Toronto – more faces of Canada today that we are so lucky to have on display, even if they will never be members of the Senate of Canada, reformed or unreformed, etc, etc.

The second item here is an additional three-member delegation representing what sections 25 and 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 call the aboriginal peoples of Canada.

In both cases the senators involved would be elected, with suitable term limits and so forth. And in both cases there are important questions about just who qualifies as entitled to vote for either the linguistic or aboriginal minority three-person delegations.

Having thought about such matters for quite a few years as well, I feel there are several possible practical approaches to this kind of problem. And, by way of celebrating the annual North American cultural holiday of the Irish, who finally figured out how to turn a (nowadays rather oxymoronic) British parliamentary democratic monarchy into an Irish parliamentary democratic republic (and in a way that would also inspire India a generation later), that is mercifully all I have to say on any branch of this or any other subject right now.

(And, on a strictly local note in Canada’s current biggest city region, may none of the green beer you may or may not drink today with such Irish folk heroes as Gurdeep Ahluwalia, Nathan Downer, Melissa Grelo, Jamie Gutfreund, Pooja Handa, Rena Heer, Jee Yun Lee, George Lagogianes, Mika Midolo, Farah Nasser, Ann Rohmer, Nalini Sharma, Katie Simpson, Cam Woolley, and Karman Wong, etc, etc, etc, etc, make you terminally or even otherwise ill! Just remember : NOW’S THE TIME TO START THINKING SERIOUSLY ABOUT REFORMING THE SENATE OF CANADA’S REPRESENTATION FORMULA, BELIEVE IT OR NOT! And I at least will raise a moderate glass of Irish whiskey to that.)

(And, on a strictly local note in Canada’s current biggest city region, may none of the green beer you may or may not drink today with such Irish folk heroes as Gurdeep Ahluwalia, Nathan Downer, Melissa Grelo, Jamie Gutfreund, Pooja Handa, Rena Heer, Jee Yun Lee, George Lagogianes, Mika Midolo, Farah Nasser, Ann Rohmer, Nalini Sharma, Katie Simpson, Cam Woolley, and Karman Wong, etc, etc, etc, etc, make you terminally or even otherwise ill! Just remember : NOW’S THE TIME TO START THINKING SERIOUSLY ABOUT REFORMING THE SENATE OF CANADA’S REPRESENTATION FORMULA, BELIEVE IT OR NOT! And I at least will raise a moderate glass of Irish whiskey to that.)