175th anniversary of early democracy struggle at Lount and Matthews Salon, Gladstone Hotel, Friday, April 12

Apr 9th, 2013 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In Brief

“Samuel Lount's and Peter Matthews' graves are marked with a broken marble column to symbolize two lives cut short” – and (some will say) to symbolize a dream of Canadian freedom and democracy that is still not quite complete.

This coming Friday, April 12 will mark the 175th anniversary of a significant event in the history of Toronto (and even Ontario and Canada writ large), that hardly anyone remembers now.

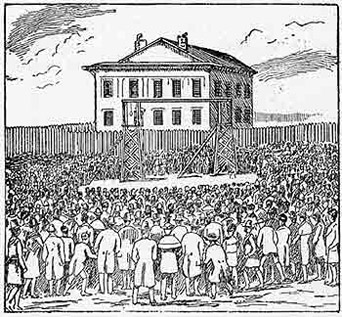

On the morning of April 12, 1838, close to the present-day intersection of King and Toronto streets downtown, Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews were publicly executed, for their quite moderate roles in the quite moderate (and immediately failed) Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837.

An old letter from John Ryerson to his brother Egerton Ryerson (after whom the present-day university is named) suggests something of the great sadness the deaths of Lount and Matthews originally evoked : “At eight o’clock today … Lount and Matthews were executed. The general feeling is in total opposition to the execution of those men. Sheriff Jarvis burst into tears when he entered the room to prepare them for execution.”

The Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, in which Lount and Matthews participated, remains a controversial historical event. Yet over the past decade or so, fresh writing by such historians as Jeffrey McNairn, Carol Wilton, and Albert Schrauwers has placed the rebellion in a broader story about the growth of popular democratic culture in what we now call Ontario, during the first half of the 19th century.

A 19th-century artist's rendering of the public hangings of Lount and Matthews, Toronto, April 12, 1838.

The British-appointed Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head described the equally controversial (if even less well remembered) Upper Canadian election of 1836 as a “moral war … between those who were for British institutions, against those who were for soiling the empire by the introduction of democracy.” And in this broader context Lount and Matthews, whatever else might be said, sacrificed their lives for what our Constitution Act, 1982 alludes to as the “free and democratic society” we enjoy in Canada today.

Samuel Lount especially is beginning to appear as (in the words of Ron Stagg at Ryerson University, a longtime student of the subject) perhaps even a “better symbol of the struggle for democracy” in the early history of what is now Ontario than the heretofore legendary 1837 rebellion leader, William Lyon Mackenzie (grandfather of Canada’s longest-serving prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1921—1926, 1926—1930, 1935—1948).

Lount and Matthews Commemoration Salon 2013 at the Gladstone Gallery

There have been a few attempts to cast this kind of mildly revisionist history of the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion in a brighter public light over the past generation or so. A less than successful but still pioneering movie called “Samuel Lount” appeared as long ago as 1985.

There have been a few attempts to cast this kind of mildly revisionist history of the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion in a brighter public light over the past generation or so. A less than successful but still pioneering movie called “Samuel Lount” appeared as long ago as 1985.

Twenty years ago, in late June 1993, “friends and family” of Lount and Matthews gathered at the Toronto Necropolis cemetery, where the two rebels of 1837 lie buried, to honour their memory and place a new plaque beside a commemorative stone originally erected in 1893. The Toronto civil rights lawyer Charles Roach, who sadly passed away himself just this past fall, also organized a few Victoria Day commemorations of Lount and Matthews in the early 2000s.

Last year a new group known as the Lount and Matthews Commemoration Committee began what it hopes will become an annual April 12 remembrance of the struggle for democracy in Canada for which Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews died, on April 12, 1838. The Committee’s initial commemoration took the form of an early morning vigil, at the time and on the spot Lount and Matthews had been hanged 174 years before.

The crowd at this early morning vigil last year was enthusiastic but inevitably small. For the 175th anniversary of the Lount and Matthews hangings this year the Committee has been moderately more ambitious. Along with a second early morning vigil, on the evening of Friday, April 12 there will be a Lount and Matthews Commemoration Salon at the second-floor Gallery of the Gladstone Hotel, 1214 Queen Street West, Toronto, from 7 to 11 PM.

As Committee chair Ashok Charles explains, Salon participants will be able to meet in a relaxed atmosphere and talk with others interested in such still controversial subjects as Lount and Matthews, the rebellions of 1837—38 in both Upper and Lower Canada (ie Ontario and Quebec), and the Canadian democratic heritage. Drinks can be purchased downstairs at the Gladstone. At the Gallery upstairs there will be snacks, videos, presentations, and the downtempo music of DJ Hans Ohm.

A.J. Haines (r), Member of the Provincial Parliament for St. Catherines, presenting the key of the William Lyon Mackenzie home at Queenston to Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King (l), June 1938.

Somewhat more formal but quite brief presentations will be held between 8:30 and 9:30 PM. They will include a sketch by noted William Lyon Mackenzie King impersonator Sean McCann, a musical tribute from modern jazz artist Wally Brooker, and a memorial on the vagaries of the 1837 rebellion at the late 20th century Toronto city hall by former City Councillor Tony O’Donohue.

Committee chair Ashok Charles stresses that everyone who may or may not be interested in Lount and Matthews is more than welcome at the Salon. In keeping with their democratic commitments, there is no cover charge. You may show up at the Gladstone Gallery whenever you like between 7 and 11 PM for free.

(Though in keeping with the often stormy ethos of old Upper Canada elections, you will still have to pay for your own drinks.)

And see also Ashok Charles and Randall White, “Lount and Matthews Commemoration Salon,” on the excellent ActiveHistory.ca website.