Machiavelli .. is he the prince of darkness who haunts democracy in America 2007?

Jul 25th, 2007 | By Randall White | Category: USA Today

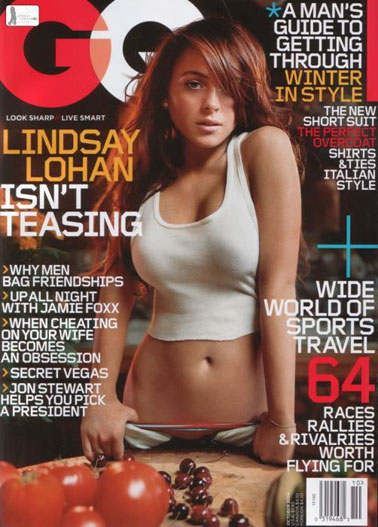

Machiavelli is “always with me” Ms. Lohan said back in 2007. Who knows whether that’s still true now? Certainly not anyone at this website, unfortunately.

Who recently told the mass media: “I was going out with someone and they said I should read Machiavelli and I was like, ‘Nah’, and then I was, ‘Ok, I’ll read it’, and now it is always with me”?

If you guessed Lindsay Lohan, go to the head of the class.

Niccolo Machiavelli, who died exactly 480 years ago this past June 21, is sometimes called the founder of the modern tough-minded science of politics, direct from the school of hard knocks. And he has many other admirers nowadays, including Stanley Bing, Allan Folsom, Stan Grimes, John Harper, Michael A. Ledeen, Don Macdonald, Harvey Mansfield, Paul A. Rahe, Karl Rove, and Gil Schwartz (aka Stanley Bing).

Some would also say that Machiavelli is the ultimate author of the disastrous Bush-Cheney Iraq War. Is that true? Or is Machiavelli really the ultimate populist “liberal republican,” who still has an important message for the troubled global village?

Some very brief historical background …

Niccolo Machiavelli was born in 1469 in the remarkable Renaissance city-state republic of Florence (or Firenze, as they say in Italian), that did so much to incubate so much of the art and science — and early industrial economy and financial system — of the modern Western world.

Niccolo Machiavelli was born in 1469 in the remarkable Renaissance city-state republic of Florence (or Firenze, as they say in Italian), that did so much to incubate so much of the art and science — and early industrial economy and financial system — of the modern Western world.

His father was a lawyer from a cultivated family who never made a lot of money but who loved books, which were just starting to appear in their modern printed form during Machiavelli’s lifetime. His mother was apparently interested in religious poetry.

Headcrop from Santi di Tito’s famous portrait of Niccolo Machiavelli, now residing in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Italy.

Niccolo Machiavelli became a Florentine civil servant, who traveled on diplomatic missions to various parts of Western Europe, and met many leading political figures of his time and place. His career as a civil servant was eventually cut short by the volatile political intrigue that beset his native city of Florence. And he retired to a very modest (and not at all prosperous) family estate in the Tuscan countryside near Florence. Here, among other things, he wrote the two books that continue to make him famous today, briefly known as The Prince and The Discourses.

Very crudely, the essential message of Machiavelli’s political writing might be reduced to something like: The crucial human activity of politics is in its nature a very tricky and even dirty business; if you get involved in it without developing some tricky and dirty skills yourself you will be eaten alive.

In 1605 the early modern English polymath intellectual and gentleman scholar Francis Bacon urged that: “We are much beholden to Machiavel and others, that write what men do, and not what they ought to do.” The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines “Machiavel” as “[Anglicized name of Niccolo Machiavelli … ] … an intriguer, an unscrupulous schemer.” And it defines “Machiavellian” as “preferring expediency to morality; practising duplicity, esp. in statecraft; astute, cunning, intriguing.”

Even a vague acquaintance with Machiavelli’s own life and times in the political jungle of the 15th and 16th century Italian city states goes some distance towards explaining his political philosophy. When the young Niccolo was not quite 10 years old Giuliano de Medici, then in charge of the Medici family bank, and in effect the entire city-state of Florence, along with his older brother Lorenzo, was stabbed 19 times at Easter Sunday mass.

In the spring of 1498, just before Machiavelli’s career as a civil servant began, the Dominican monk Girolamo Savonarola, who some four years earlier had expelled the Medici family and established a kind of theocratic democracy in Florence, was burned in the Piazza della Signoria.

In 1513, when the Medici family returned to Florence and Machiavelli’s main civil service career came to an end, he was himself briefly imprisoned and tortured, before being released to return to his modest country estate, where he would write what only much later became his famous books on the tricky and dirty business of politics.

Machiavelli in Washington (and Hollywood?) today …

There are various ways of connecting Machiavelli with what are increasingly widely perceived as the quite tragic misadventures of the Bush-Cheney administration in Washington today. In the spring of 1997, e.g., Michael A. Ledeen of the American Enterprise Institute gave a rather alarming lecture called “Machiavelli for Moderns.”

There are various ways of connecting Machiavelli with what are increasingly widely perceived as the quite tragic misadventures of the Bush-Cheney administration in Washington today. In the spring of 1997, e.g., Michael A. Ledeen of the American Enterprise Institute gave a rather alarming lecture called “Machiavelli for Moderns.”

According to Machiavelli as interpreted by Michael Ledeen,. In our current troubled era: “if a free society has been corrupted, it cannot be freely saved; only a single ruler with enormous power can carry it off.”

This argued that “America today seems to fulfill Machiavelli’s description of the good state headed downward.” According to Machiavelli as interpreted by Mr. Ledeen, “if a free society has been corrupted, it cannot be freely saved; only a single ruler with enormous power can carry it off.” In the midst of Bill Clinton’s “personal corruption and … rejection of military virtue,” the urgent question was: “Where to find a leader prepared to enter into evil and take extraordinary measures,” and so restore America to her rightful place in the mind of Michael Ledeen?

Several years later, “when the Washington Post published a list of the people whom Karl Rove, President George W Bush’s closest advisor, regularly consults for advice outside the administration, foreign policy veterans were shocked when Michael Ledeen popped up as the only full-time international affairs analyst … The two met after Bush’s election,’ the Post reported cheerfully, quoting Ledeen about Rove’s request that any time you have a good idea, tell me.’ More than once, Ledeen has seen his ideas, faxed to Rove, become official policy …”

According to Wikipedia, “Ledeen specifically called for the deposition of Saddam Hussein’s regime by force in 2002,” and aggressively belittled former Bush Senior advisor Brent Scowcroft’s shrewd advice against such an adventure. Scowcroft, Ledeen urged, “fears that if we attack Iraq I think we could have an explosion in the Middle East. It could turn the whole region into a caldron and destroy the War on Terror.’ One can only hope [Mr. Ledeen carried on] that we turn the region into a cauldron, and faster, please. If ever there were a region that richly deserved being cauldronized, it is the Middle East today. If we wage the war effectively, we will bring down the terror regimes in Iraq, Iran, and Syria, and either bring down the Saudi monarchy or force it to abandon its global assembly line to indoctrinate young terrorists … That’s our mission in the war against terror.”

Several years later again, of course, time does seem to have proved (for any who may have doubted earlier on) that Brent Scowcroft and not Michael Ledeen was right. Does this also mean that Niccolo Machiavelli’s now almost 500-year-old modern political wisdom is finally approaching its ultimate best-before date too?

(As Lindsay Lohan’s latest arrest in Santa Monica might also seem to suggest: the fact that Machiavelli from the high tide of Florentine Renaissance backstabbing and intrigue “is always with me” does not seem to have done Ms. Lohan all that much good lately either.)

Machiavelli and the future of democracy in America …

As with so much else about America and the Iraq War these days, the best answer here for the moment still seems to be a giant question mark. There are many, e.g., who might say that the mind of Brent Scowcroft is just a different (and more sensible?) version of Machiavellian political wisdom than the mind of Michael Ledeen.

At the beginning of his 1997 lecture on the subject Mr. Ledeen himself noted that the eminent British political philosopher Isaiah Berlin once “counted twenty different interpretations” of the cunning Florentine’s gospel – “ranging from Machiavelli-the-Antichrist to Machiavelli-the-tortured-humanist.” Within this wide array of possible American Machiavellis for the 21st century, others again might urge, there may even be some room for the tough-minded Hillary Clinton.

There is a forward-looking side to Machiavelli, even today, and some would say his most cunning and hopeful American disciple finally did appear in 2008?

At the same time, it seems at least arguable as well that any version of an American Machiavelli nowadays is finally turning his or her back on the advice offered to the still very exceptional new republic by its first president, in his Farewell Address of 1796. As he retired to Mount Vernon George Washington famously warned his “Friends and Citizens” to beware of “frequent interruption of their peace by foreign nations … foreign alliances, attachments, and intrigues … the impostures of pretended patriotism,” and “the necessity of those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.”

Even in the midst of so much agreement nowadays that, like Vietnam in an earlier era, the War in Iraq has been another tragic American foreign policy blunder, there still seem very few echoes of Washington’s Farewell Address in the capital city to which he gave his name. And the bloody Old World intrigues of Niccolo Machiavelli, you might almost say, were exactly the kinds of things that Washington hoped his New World country across the sea could somehow avoid.

So it may finally be true that, whatever happens exactly in Iraq now, over the past number of years something in and about America actually has changed forever. There are now such things as American Machiavellis. And in one shape or form or another, perhaps they are never going to go away? (Just ask Tony Soprano in New Jersey, still others might say.)

So it may finally be true that, whatever happens exactly in Iraq now, over the past number of years something in and about America actually has changed forever. There are now such things as American Machiavellis. And in one shape or form or another, perhaps they are never going to go away? (Just ask Tony Soprano in New Jersey, still others might say.)

So too the key question for the US progressive left right now may finally be: What does the hard-boiled wisdom of Niccolo Machiavelli still have to tell us about how to help the real democracy in America stand up and prosper in the very challenging decades that so clearly lie ahead? It would be refreshing if the premature 2008 Democratic presidential debates on TV would start communicating even just a little about that. No matter how important you think the morality of both the people and their elected leaders is for real democratic politics, it is still important, as Francis Bacon said long ago, to pay very close attention to “what men do, and not what they ought to do.” (And of course nowadays that goes for women too.)

[New images added February 4, 2011.]