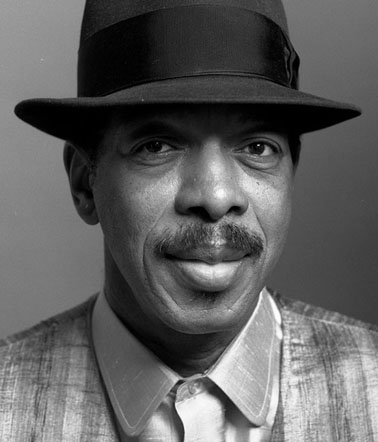

Ornette Coleman grass roots jazz anarchist RIP ..

Jun 14th, 2015 | By Citizen X | Category: In Brief

Sadly, Ornette Coleman – “American jazz saxophonist, violinist, trumpeter and composer … one of the major innovators of the free jazz movement of the 1960s” – died in Manhattan of a heart attack this past Thursday, June 11, at the ripe old age of 85.

He came on stream in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when people my age were first learning about “America’s Classical Music.” Â As both the New York Times and CBC News obituaries have properly observed, he was (especially at first) a controversial figure.

I’m no expert but I think Ben Ratliff in the New York Times has aptly summarized the essential Ornette Coleman achievement :

“Mr. Coleman widened the options in jazz and helped change its course. Partly through his example … jazz became less beholden to the rules of harmony and rhythm while gaining more distance from the American songbook repertoire … His own music … Â embodied a new type of folk song: providing deceptively simple melodies for small groups with an intuitive, collective musical language and a strategy for playing without preconceived chord sequences.”

L to r : Thelonious Monk, Howard McGhee, Roy Eldridge, and Teddy Hill outside Minton's Playhouse in New York, one of the birthplaces of bebop and/or modern jazz, around 1940. Photo: WILLIAM GOTTLIEB.

The scepticism about all this among an older generation of musicians is illustrated by some remarks from the trumpet player Roy Eldridge, quoted in both the New York Times and CBC News obituaries : “I listened to Coleman high and I listened to him cold sober … I even played with him. I think he’s jiving, baby.” (Where “jiving” means “making it up,” or as the online urban dictionary says, “To act foolish, to joke around or act in a random nature.”)

The marvels of You Tube in our own time allow us to quickly compare the different musical offerings of Roy Eldridge and Ornette Coleman in the late 1950s.

On the one hand the brilliant talents of Mr. Eldridge and the even older and enormously accomplished tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins – rigorously disciplined by the rules of harmony and rhythm and preconceived chord sequences – are on display in a still extant recording of a 1957 concert at The Opera House in Chicago. (Accompanied by three-quarters of the Modern Jazz Quartet from the same era : John Lewis [piano], Percy Heath [bass] and Connie Kay [drums].)

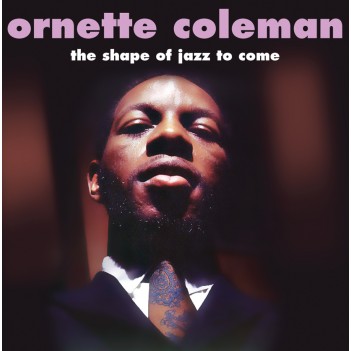

On the other hand, the new vistas of Ornette Coleman’s free jazz can be sampled in his 1959 LP album The Shape of Jazz to Come. Here Mr. Coleman is accompanied by his friends Don Cherry (cornet), Charlie Haden (bass), and Billy Higgins (drums). Â And an obituary comment on the You Tube video from a lady who just calls herself Meg L probably summarizes what many Coleman enthusiasts still feel and believe : “Ornette Coleman’s music sounded so wild when I used to listen to it as a young girl. It still sounds way ahead of its time today. A true iconoclast. Rest in power, Mr Coleman, and thank you for setting music free.”

On the other hand, the new vistas of Ornette Coleman’s free jazz can be sampled in his 1959 LP album The Shape of Jazz to Come. Here Mr. Coleman is accompanied by his friends Don Cherry (cornet), Charlie Haden (bass), and Billy Higgins (drums). Â And an obituary comment on the You Tube video from a lady who just calls herself Meg L probably summarizes what many Coleman enthusiasts still feel and believe : “Ornette Coleman’s music sounded so wild when I used to listen to it as a young girl. It still sounds way ahead of its time today. A true iconoclast. Rest in power, Mr Coleman, and thank you for setting music free.”

But does jazz really work better when it’s free ?

What some of us who remain primarily attached to the great modern jazz era of 1940 to 1970 feel and believe, of course, is that free jazz has finally shown why and how, for at least most musicians in most times and places, jazz actually does work best when it sticks fairly close to at least some version of  the rules of harmony and rhythm and preconceived chord sequences.

Charlie Parker (1) relaxing with his late 40s/early 50s trumpet player, Red Rodney. As the band’s only white man, Rodney was billed as “Albino Red” when the group played the then still racially segregated southern USA. Photo: WILLIAM GOTTLIEB.

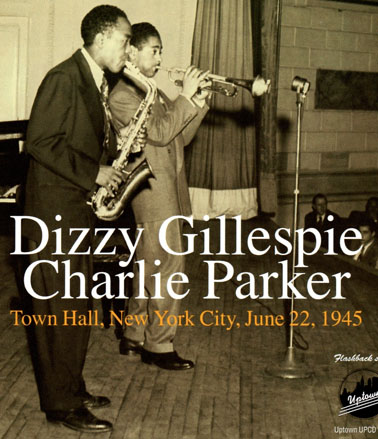

As the trumpet-playing white man Red Rodney said on a Toronto radio show many years ago now, the bebop jazz pioneered by the likes of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie in the early 1940s remains the hardest jazz to play. And finally, it does seem to me, it is also the most interesting jazz to listen to and learn from, again and again.

Charlie Parker (1920—1955) in this sense greatly expanded the room within the rules of harmony and rhythm and preconceived chord sequences available to the pioneer generation of traditional jazz musicians, ultimately led by Louis Armstrong (or so the story goes).

And this more or less followed a trend toward extending and expanding the rules inside the European classical tradition in the later 19th and earlier 20th centuries. (Both Parker and Hawkins, eg, listened to classical recordings in some of their spare time.)

In his New York Times obituary Ben Ratliff actually tries to place Ornette Coleman in some Charlie Parker tradition. Coleman’s early work was, on this view, “a personal answer to his fellow alto saxophonist and innovator Charlie Parker.” And this stage of his career is best reflected in his first album in 1958, Something Else!!!! The Music of Ornette Coleman : “No recording of Mr. Coleman’s,” Ratliff writes, “holds closer to the model of Charlie Parker.”

In his New York Times obituary Ben Ratliff actually tries to place Ornette Coleman in some Charlie Parker tradition. Coleman’s early work was, on this view, “a personal answer to his fellow alto saxophonist and innovator Charlie Parker.” And this stage of his career is best reflected in his first album in 1958, Something Else!!!! The Music of Ornette Coleman : “No recording of Mr. Coleman’s,” Ratliff writes, “holds closer to the model of Charlie Parker.”

Yet there is a vast difference between extending and expanding the rules as Charlie Parker did, and virtually abandoning the rules – which is, as best as I can make out, what Ornette Coleman did, for the most part. For Coleman freedom is largely an absence of discipline. For Parker freedom means the more disciplined you are, the higher you can fly.

Charlie Parker and Ornette Coleman compared

Ben Ratliff writes that when Mr. Coleman “was learning to play the saxophone … he did not yet understand that because of transposition between instruments, a C in the piano’s ‘concert key’ was an A on his instrument. When he learned the truth, he said, he developed a lifelong suspicion of the rules of Western harmony and musical notation.”

As many of us can remember from our youths, the sheer tedium of even half-mastering “the rules of Western harmony and musical notation” can make philosophies that dismiss these rules as too restrictive especially attractive. But this was not Charlie Parker’s approach at all.

As many of us can remember from our youths, the sheer tedium of even half-mastering “the rules of Western harmony and musical notation” can make philosophies that dismiss these rules as too restrictive especially attractive. But this was not Charlie Parker’s approach at all.

In a fascinating 1954 Boston radio interview with fellow alto saxophonist Paul Desmond (who played with Dave Brubeck for many years), Parker (aka Bird etc) confessed : “I put quite a bit of study into the horn, that’s true. In fact the neighbors threatened to ask my mother to move once when we were living out West. She said I was driving them crazy with the horn. I used to put in at least 11 to 15 hours a day.”

And then Desmond recalled : “I heard a record of yours a couple of months ago … and I heard a little 2 bar quote from the Klosé book that was like an echo from home…”  (The H. Klosé Complete Method for all Saxophones and  H. Klosé 25 Daily Exercises For Saxophone are still more or less well known exercise and instruction books.)

Parker replied : “Well that was all done with books, you know. Naturally, it wasn’t done with mirrors, this time it was done with books.”

Parker replied : “Well that was all done with books, you know. Naturally, it wasn’t done with mirrors, this time it was done with books.”

And then after some further discussion on the virtues of books, the founder of modern jazz concluded : “study is absolutely necessary, in all forms. It’s just like any talent that’s born within somebody, it’s like a good pair of shoes when you put a shine on it … schooling brings out the polish of any talent … Â Einstein had schooling, but he has a definite genius, you know, within himself, schooling is one of the most wonderful things there’s ever been …”

Ornette Coleman and the grass roots anarchist tradition in jazz

I prefer myself the kind of jazz that flows from Charlie Parker’s convictions about the importance of study, exercise books, and schooling – as well as (in other words of his to Paul Desmond in Boston in 1954) : “ever since I’ve ever heard music I’ve thought it should be very clean, very precise – Â as clean as possible anyway … ”

At the same time, maybe I have mellowed more than I sometimes think since my youth. I’d agree nowadays that Ornette Coleman has “widened the options in jazz,” as  Ben Ratliff in the New York Times has explained.

Similarly, I still remember and take seriously enough something I read in Down Beat or wherever, back in the day when Ornette Coleman had just burst upon the scene in the early 1960s and was still very controversial. Someone who still remembered the controversy about bebop and Charlie Parker in the earlier 1940s pointed out that way back then even Parker’s worst critics would agree that he was at least a superb technician on the alto saxophone.

Charlie Parker, that is, was not just a controversial jazz innovator, he was a gifted and accomplished instrumentalist, who had “put quite a bit of study into the horn, that’s true.” He was a great saxophone player as well as a great jazz musician.

Not even Ornette Coleman’s warmest admirers would or could claim the same for him. He may have been a great jazz musician (oh, ok, I’ll agree : he probably was). But no student of the saxophone as something that can, if you put your mind to it, be mastered technically, in one degree or another, could ever allow that Ornette Coleman was a great saxophone player.

Not even Ornette Coleman’s warmest admirers would or could claim the same for him. He may have been a great jazz musician (oh, ok, I’ll agree : he probably was). But no student of the saxophone as something that can, if you put your mind to it, be mastered technically, in one degree or another, could ever allow that Ornette Coleman was a great saxophone player.

Having spent a little time listening to Mr. Coleman again, however, I think I would agree that, while he was not a technically accomplished musician on anything remotely approaching what Ben Ratliff calls “the model of Charlie Parker,” Ornette Coleman was a real musical artist.

Mr. Coleman used modest technical resources (and an even principled reluctance to get too involved in “the rules of Western harmony and musical notation” – even though as Ratliff also stresses, some parts of his playing do intermittently rely “on polished written melodies”), to create an innovative and more or less spontaneous music that attracted listeners.

One or another version of this less disciplined and, in some senses, more “free” or even anarchic approach to music has always been part of the American jazz tradition that stretches back to the mouth of the Mississippi River in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And it has been part of Ornette Coleman’s achievement to reinvigorate this side of the tradition, in a modern jazz scene that was growing increasingly obsessed with schooling and technique, and elegant mastery of (for want of better words) “the rules of Western harmony and musical notation.”

One or another version of this less disciplined and, in some senses, more “free” or even anarchic approach to music has always been part of the American jazz tradition that stretches back to the mouth of the Mississippi River in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And it has been part of Ornette Coleman’s achievement to reinvigorate this side of the tradition, in a modern jazz scene that was growing increasingly obsessed with schooling and technique, and elegant mastery of (for want of better words) “the rules of Western harmony and musical notation.”

There may even be a kind of non-technical side to Charlie Parker and his philosophy of music that Ornette Coleman has continued to explore – in stronger and deeper ways than Bird’s more  technically obsessed disciples. To me the freedom achieved by the hard-earned technique that finally gave Charlie Parker the ability to make his music almost literally fly is a higher-order freedom than what is on display in the free jazz creations of Ornette Coleman. But even I find some of Coleman’s creations interesting. And his music has passed the only altogether crucial test of attracting a big enough audience to support the performers.

Ornette Coleman achieved another great distinction that tragically eluded Charlie Parker. He lived 50 years longer.

Coleman was not, I think, at all as great a jazz innovator as Parker, or as brilliant a musician. But Ornette Coleman knew things about human survival that the Yardbird either did not know or did not take seriously enough. These things no doubt found their way into Coleman’s music too – and that also helps account for its attractions.

Coleman was not, I think, at all as great a jazz innovator as Parker, or as brilliant a musician. But Ornette Coleman knew things about human survival that the Yardbird either did not know or did not take seriously enough. These things no doubt found their way into Coleman’s music too – and that also helps account for its attractions.

He was, as Ben Ratliff has once again nicely explained, “a kind of musician-philosopher, whose interests reached well beyond jazz … Â a native avant-gardist, personifying the American independent will.” Â (Or, as one Toronto financial manager and jazz musician of the early 21st century more simply declared on facebook on June 11 : “RIP Ornette Coleman. A true original.”)

What your writing shows is a the mentality of many conservative bop purists I’ve met, and a total cluelessness about Ornette and his contributions. What you are talking about is academic bullshit, art does not live to be straitjacketed by some rigid book of rules that only you can play by, kind of attitude that makes jazz dead classical music. Remember that his innovations have lasted as long as bebop and are just as valid to many modern musicians much greater than you. Plus he was a superb original composer a genius of melodies, many of those are still being explored. Ornette will be greater in death than you will ever be in your lifetime, so think about that.