There’s Pontiac .. then there’s Pontiac .. both worth a few historical tears

Jun 5th, 2009 | By L. Frank Bunting | Category: Heritage Now Mostly, the historian Jill Lepore wrote in a New Yorker article a few months ago, “we’re bankrupt of history.” And in the wake of General Motors’ April 27, 2009 decision to discontinue the manufacture of Pontiac automobiles (and the still more recent GM filing for US bankruptcy protection on June 1), the historian Gordon Mitchell Sayre seems prophetic: “I would guess that fewer than one in ten of those who drive the automobiles that bear his name could identify the historical Pontiac” – the War Chief of the Ottawas who may or may not have engineered the formidable North American Indian uprising of 1763, once known as The Conspiracy of Pontiac.

Mostly, the historian Jill Lepore wrote in a New Yorker article a few months ago, “we’re bankrupt of history.” And in the wake of General Motors’ April 27, 2009 decision to discontinue the manufacture of Pontiac automobiles (and the still more recent GM filing for US bankruptcy protection on June 1), the historian Gordon Mitchell Sayre seems prophetic: “I would guess that fewer than one in ten of those who drive the automobiles that bear his name could identify the historical Pontiac” – the War Chief of the Ottawas who may or may not have engineered the formidable North American Indian uprising of 1763, once known as The Conspiracy of Pontiac.

Sayre’s remarks hold for Canadian as well as US drivers of Pontiac automobiles. And yet Canada survives today partly because of what Pontiac did in the Great Lakes wilderness of the 1760s. In the early 21st century a properly decolonized country that was not quite so bankrupt of its own history might cast the Ottawa war chief in almost as prominent a role as the first prime minister of the Canadian confederation of 1867, John A. Macdonald! (Or as the still compelling fur-trade historian Harold Innis declared back in 1930: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.”)

NOTE FROM COUNTERWEIGHTS EDITORS: Having recovered from his earlier assault on the vastness of Ernest Hemingway L. Frank Bunting has altogether outdone himself in loquacity in what follows here. Those only interested in Pontiac automobiles might just want to read sections 1, 2, and 10 below. Those not interested in automobiles, but deeply intrigued by the aboriginal war chief and his rebellion of 1763-1766, might want to skip sections 1 and 2. Those interested only in current events might just want to read sections 9 and 10. Mr. Bunting tells us that anyone who does read all 10 sections carefully will some day be rewarded by an andacwander ceremony in the happy hunting ground up in the sky.

1. A quick bow to the more recent history of the automobile: the first half-century …

It seems that the very first Pontiac automobile in North America was named after the suburban city of Pontiac, Michigan, in Oakland County just northwest of the city of Detroit. But Pontiac, Michigan was itself named after the 18th century Ottawa war chief, who lived in the Detroit area as an adult and perhaps long before.

It seems that the very first Pontiac automobile in North America was named after the suburban city of Pontiac, Michigan, in Oakland County just northwest of the city of Detroit. But Pontiac, Michigan was itself named after the 18th century Ottawa war chief, who lived in the Detroit area as an adult and perhaps long before.

A Pontiac, Michigan firm known as the Pontiac Spring and Wagon Works was incorporated in July 1899. In 1907 this local wagon works decided to produce automobiles as well. The very first Pontiac cars – so-called highwheelers weighing 1,000 pounds and powered by a two-cylinder water-cooled 12 horsepower engine – were apparently delivered to customers early in 1908.

Later that same year the Pontiac Spring and Wagon Works merged with the Oakland Motor Car Company. And by the end of 1909 the merged company had been purchased by a fledgling conglomerate known as General Motors Corporation.

The first General Motors car that flowed from this earliest history was called the Oakland. In 1926, however, a Pontiac brand was re-introduced as a “‘companion’ marque[e]” to GM’s Oakland Motor Car line.

The first General Motors car that flowed from this earliest history was called the Oakland. In 1926, however, a Pontiac brand was re-introduced as a “‘companion’ marque[e]” to GM’s Oakland Motor Car line.

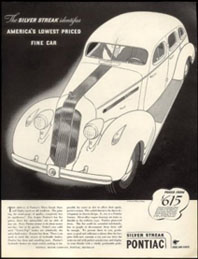

According to what appears to be a reliable enough Wikipedia article: “Pontiac began by selling cars offering 40 hp … straight 6-cylinder engines in the Pontiac Chief of 1927 … The Chief sold 39,000 units within six months of its appearance at the 1926 New York Auto Salon … The next year, it became the top-selling six in the US … By 1933, it had moved up to producing the cheapest cars available with straight eight-cylinder … engines. This was done by using many components from the 6-cylinder Chevrolet, such as the body. ” By 1935 the “Pontiac Silver Streak” was being advertised as “America’s Lowest Priced Fine Car.”

For the next 20 years the Pontiac was something of a souped-up Chevrolet – a slightly more luxurious version of GM’s entry-level vehicle for the great democratic masses. During this period the brand’s identification with the ancient history of the Ottawa war chief from Detroit was quite prominent: “An American Indian head[dress] was used as a logo until 1956. This was updated to the currently used American Indian red arrowhead design for 1957.”

2. The automobile’s next half-century: America’s first muscle cars …

Another “identifying feature of [earlier] Pontiacs were their ‘Silver Streaks’ – one or more narrow strips of stainless steel which extended from the grille down the center of the hood … Although initially a single band, this stylistic trademark doubled to two for 1955—56. The Silver Streaks were discontinued the same year [as] the Indian Head emblems … 1957.”

Another “identifying feature of [earlier] Pontiacs were their ‘Silver Streaks’ – one or more narrow strips of stainless steel which extended from the grille down the center of the hood … Although initially a single band, this stylistic trademark doubled to two for 1955—56. The Silver Streaks were discontinued the same year [as] the Indian Head emblems … 1957.”

There was something deeper behind these stylistic changes. Until the mid 1950s “the Pontiac was a quiet, solid car, but not especially powerful.” But in “1956 when Semon ‘Bunkie’ Knudsen became general manager of Pontiac, with the aid of his new heads of engineering, E. M. Estes and John Z. De Lorean, he immediately began reworking the brand’s image.”

One of the first steps did involve “the removal of the … trademark ‘silver streaks’ from the … 1957 models.” But another “step was … the first Bonneville – a limited-edition Star Chief convertible that showcased Pontiac’s first fuel-injected engine. Some 630 Bonnevilles were built for 1957, each with a retail price of nearly $5800.” You “could buy a Cadillac for that price, [but] the Bonneville raised new interest in what Pontiac now called ‘America’s No. 1 Road Car.'”

One of the first steps did involve “the removal of the … trademark ‘silver streaks’ from the … 1957 models.” But another “step was … the first Bonneville – a limited-edition Star Chief convertible that showcased Pontiac’s first fuel-injected engine. Some 630 Bonnevilles were built for 1957, each with a retail price of nearly $5800.” You “could buy a Cadillac for that price, [but] the Bonneville raised new interest in what Pontiac now called ‘America’s No. 1 Road Car.'”

In the 1960s such high-performance Pontiac models as the Firebird, Grand Prix, GTO (one of America’s first muscle cars), and Tempest locked in this new trend. Then there were classics like the Grand Am in the 1970s and the Trans Am in the 1980s. Then, somewhere in the 1990s it seems, the Pontiac brand began to lose its way.

In the spring of 2009 commentators like Dan McFeely at IndyStar.com have been moaning: “Thank goodness Smokey and the Bandit was made in 1977 – back when real men drove Pontiacs … Without his macho black Pontiac Trans Am, Burt Reynolds (the Bandit) might have looked pretty wimpy running away from Jackie Gleason (Sheriff Buford T. Justice) … Ah, Pontiac – the brand that gave us the Trans Am, the Firebird, the GTO, the cool car (KITT) on the TV show Knight Rider. Where have you gone?”

In the spring of 2009 commentators like Dan McFeely at IndyStar.com have been moaning: “Thank goodness Smokey and the Bandit was made in 1977 – back when real men drove Pontiacs … Without his macho black Pontiac Trans Am, Burt Reynolds (the Bandit) might have looked pretty wimpy running away from Jackie Gleason (Sheriff Buford T. Justice) … Ah, Pontiac – the brand that gave us the Trans Am, the Firebird, the GTO, the cool car (KITT) on the TV show Knight Rider. Where have you gone?”

McFeely carries on: “‘April 27th, 2009, was a bad day for Pontiac, GM and me,’ said Bill Sanders … a Pontiac lover who blogs about his devotion to GTOs.” The announcement that “Pontiac was history” distressed “loyal drivers such as Sanders … president of the Indy GTO Association, chairman of the Auto Clubs Council of Indiana and a member of the Hoosier Pontiac Oakland Club … ‘Yes, I’m mad that Pontiac is going away,’ Sanders said.” But what upsets him even more is “the way the nameplate has been mishandled over the last 20-plus years. This was a freight train that’s been coming for a long time.”

There remains one other General Motors automobile brand that still looks back to the ancient 18th century history of the French and Indian Great Lakes region – when real men were even more macho than Burt Reynolds. This is of course the Cadillac – named after Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, who founded what is now the US city of Detroit in 1701, for the Sun King of France, Louis XIV, and his many North American Indian allies. [CW EDS : And on a quick dust-up edit in late February 2023 we’re certain that nowadays even Mr. Bunting would say North American Indigenous allies. Our apologies for this and other similar anachronisms that may appear in what follows.]

There remains one other General Motors automobile brand that still looks back to the ancient 18th century history of the French and Indian Great Lakes region – when real men were even more macho than Burt Reynolds. This is of course the Cadillac – named after Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, Sieur de Cadillac, who founded what is now the US city of Detroit in 1701, for the Sun King of France, Louis XIV, and his many North American Indian allies. [CW EDS : And on a quick dust-up edit in late February 2023 we’re certain that nowadays even Mr. Bunting would say North American Indigenous allies. Our apologies for this and other similar anachronisms that may appear in what follows.]

It is sometimes thought that the Chevrolet falls into a similar class, but it does not. In the early 20th century “Chevrolet was founded by Louis Chevrolet (Swiss-French) and William C. Durant (American). Louis Chevrolet was a race-car driver, and William Durant … head of Buick Motor Company, prior to founding GM … had hired Chevrolet to drive Buicks in promotional races.”

3. The historical Pontiac of the 18th century: the little we know of his early years …

What Gordon Mitchell Sayre calls the historical Pontiac, Ottawa war chief in the mid 18th century Detroit region, would probably be pleased to see his name on some of the most memorable American muscle cars of the late 20th century. That much at least we seem able to glean from what little is known about him.

What Gordon Mitchell Sayre calls the historical Pontiac, Ottawa war chief in the mid 18th century Detroit region, would probably be pleased to see his name on some of the most memorable American muscle cars of the late 20th century. That much at least we seem able to glean from what little is known about him.

It is sometimes said that he was born around 1720 – “between 1712 and 1725” in any case. Exactly where is unclear. Some sources say “perhaps at an Ottawa village on the Detroit or Maumee Rivers.” Some also say that “Pontiac’s father was an Ottawa and his mother an Ojibwa.” Other sources report that “one of his parents was a Miami.”

Just how he arrived in the region around the French fort at Detroit is equally mysterious. He may have been born there. Or in “1736, 200 Ottawa warriors are believed to have been settled in the neighbourhood of Detroit.” If he did grow up in the Detroit region, or arrive there before 1736, since 1732 the resident Ottawa “had not lived near the French fort, but rather across from it, on the other side of the river [in what is now Canada], in a community of 800 to 1,000 inhabitants.”

Just how he arrived in the region around the French fort at Detroit is equally mysterious. He may have been born there. Or in “1736, 200 Ottawa warriors are believed to have been settled in the neighbourhood of Detroit.” If he did grow up in the Detroit region, or arrive there before 1736, since 1732 the resident Ottawa “had not lived near the French fort, but rather across from it, on the other side of the river [in what is now Canada], in a community of 800 to 1,000 inhabitants.”

The picture becomes somewhat less murky towards the middle of the 18th century. Pontiac was apparently “a witness to the conspiracy of Orontony, the Huron chief at Sandosk (in the vicinity of [present-day] Sandusky, Ohio)” in 1747. And it is written that by this point Pontiac had become “an Ottawa war leader.”

In European terms the conspiracy of Orontony was against the French and for the British (in protest against an increase in French prices for fur trade goods). On his own subsequent testimony, Pontiac witnessed but did not join this conspiracy. The guiding light of his career as an Ottawa war chief, he claimed, was “faultless loyalty to the French” (or to “Onontio,” the French Governor of Canada at Quebec City).

In this particular European loyalty Pontiac was just following the great majority of his contemporaries among the North American aboriginal peoples of the Great Lakes interior or upper country (or “le pays d’en haut”). The French empire in the region, the historian Richard White has explained, was ultimately held together by a “Janus-faced alliance” between the Algonquian-speaking peoples and “Onontio, the French governor at Quebec.”

In this particular European loyalty Pontiac was just following the great majority of his contemporaries among the North American aboriginal peoples of the Great Lakes interior or upper country (or “le pays d’en haut”). The French empire in the region, the historian Richard White has explained, was ultimately held together by a “Janus-faced alliance” between the Algonquian-speaking peoples and “Onontio, the French governor at Quebec.”

This French and Indian alliance “preserved Canada.” And what White calls its “Janus-faced” nature was especially intriguing: “Facing east, the French appeared at the head of an Algonquian host. This was the alliance armed and breathing fire in the service of imperial France, the alliance that … repeatedly fought the far more numerous British to a standstill.”

On its “western face” the alliance was “largely Algonquian in form and spirit.” The aboriginal allies saw Onontio as a fountain of “patriarchal benevolence.” As the price of their loyalty the Algonquians [Chippewa, Delaware, Fox, Menominee, Miami, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Shawnee, etc] demanded that Onontio be “a father who mediated more often than he commanded, who forgave more often than he punished, and who gave more than he received.”

4. Pontiac and the French and Indian War, 1754—1763

This Janus-faced French and Indian alliance helped the French empire in the North American interior dominate the first several years of what is variously known as the French and Indian War of 1754—1763, or the Seven Years War of 17561763, or (in an earlier era at least) the British Conquest of Canada, or (in the francophone-majority Canadian Province of Quebec even today) just La Conquête – despite the vastly greater demographic weight of the British American Thirteen Colonies on the Atlantic seaboard.

This Janus-faced French and Indian alliance helped the French empire in the North American interior dominate the first several years of what is variously known as the French and Indian War of 1754—1763, or the Seven Years War of 17561763, or (in an earlier era at least) the British Conquest of Canada, or (in the francophone-majority Canadian Province of Quebec even today) just La Conquête – despite the vastly greater demographic weight of the British American Thirteen Colonies on the Atlantic seaboard.

Pontiac may have participated in some of the early French victories in the North American branch of what ultimately became a global imperial conflict. By the middle of the 18th century the French empire in the North American interior – stretching from Quebec City and Montreal in the St. Lawrence Valley to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley, all the way south to New Orleans – had become profoundly worried about the westward rumblings of the Anglo-American settlement frontier, in the British Thirteen Colonies on the Atlantic coast.

Preamble at Pickawillany

At the time these rumblings were focused on the Ohio Valley (or “Ohio Country”) south of the Great Lakes. By the early 1750s the French and their Indian allies were working hard to stamp out British influence in this region.

In 1752 a force led by the Métis warrior from the upper Great Lakes outpost at Michilimackinac, Charles-Michel Mouet de Langlade (son of Augustin Mouet de Langlade, a prominent fur trader, and Domitilde, sister of the Algonquian-speaking Ottawa chief Nissowaquet) destroyed the pro-British Miami village of Pickawillany in present-day Piqua, Ohio, just after it had been visited by the British fur trader and frontier real estate developer George Croghan. Langlade’s force included some “240 Canadians and Ottawas, one of whom was perhaps Pontiac.”

Early French and Indian victories

The subsequent last great French and Indian War fought by the British empire in North America more or less officially began in 1754, when the French and their Indian allies defeated another British American attempt to establish a fresh foothold in the Ohio Valley near present-day Uniontown, Pennsylvania, led by a 22-year-old George Washington from Virginia.

The subsequent last great French and Indian War fought by the British empire in North America more or less officially began in 1754, when the French and their Indian allies defeated another British American attempt to establish a fresh foothold in the Ohio Valley near present-day Uniontown, Pennsylvania, led by a 22-year-old George Washington from Virginia.

A year later the French and Indians turned back a major British assault on Fort Duquesne (later Fort Pitt, in present-day Pittsburgh), by some 2,400 men under Major General Edward Braddock of the regular British army. According to the Quebec historian Louis Chevrette: “Pontiac may have been among the Indians, some 800 to 1,000 strong, who, with Jean-Daniel Dumas and the French garrison, inflicted a terrible defeat on the British not far from the threatened fort.”

Louis Chevrette also notes: “Some 300 Ottawas from Detroit and 700 from Michilimackinac remained at Fort Duquesne until 1756 … A year later [the Marquis de] Montcalm brought a certain number of these Algonkians to Montreal and took them on an expedition against Fort William Henry … [in New York]. Among his forces were 30 Ottawas from Pontiac’s village.”

In 1757 “Pontiac delivered a speech before Pécaudy de Contrecoeur at Fort Duquesne. He maintained that George Croghan had just tried to deceive him by claiming that Quebec had fallen and had called upon him to become an ally of the British. Pontiac said that he had resisted his advances and recalled the advantageous promises made to the friends of the French.”

Demography and the British Navy

By 1758 the tide had begun to turn against the French empire in America. There were no more than 70,000 to 80,000 people of European descent living in the Canada of the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes. There were more than 1 million such people in the British Thirteen Colonies on the Atlantic coast. Superior British numbers and resources – and the British Royal Navy`s increasing might on the oceans of the world – were beginning to take hold.

By 1758 the tide had begun to turn against the French empire in America. There were no more than 70,000 to 80,000 people of European descent living in the Canada of the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes. There were more than 1 million such people in the British Thirteen Colonies on the Atlantic coast. Superior British numbers and resources – and the British Royal Navy`s increasing might on the oceans of the world – were beginning to take hold.

Even so, when General John Forbes`s British American force of more than 6,000 moved on Fort Duquesne once again, in mid September 1758, a French and Indian garrison less than one-tenth that size at first beat back the invaders. And: “The French continued to occupy Fort Duquesne until November 26, when the garrison set fire to the fort and left under the cover of darkness. As the British marched up to the smoldering remains, they were confronted with an appalling sight. The Indians had cut off the heads of many of the dead Highlanders and impaled them on the sharp stakes on top of the fort walls, with their kilts displayed below.”

The fall of Quebec and Montreal

Very late in 1758, Louis Chevrette has written, “some Ottawas from Detroit were still fighting for France not far from Fort Duquesne, which the French abandoned to John Forbes.” Yet by the end of July 1759 the British had also taken the impressive stone structure at the French Fort Niagara, where the Niagara River and Niagara Falls rush down into Lake Ontario. On September 13, 1759 the British finally took Quebec – the great citadel of the French empire in America, at the top of a cliff on the St. Lawrence River.

Very late in 1758, Louis Chevrette has written, “some Ottawas from Detroit were still fighting for France not far from Fort Duquesne, which the French abandoned to John Forbes.” Yet by the end of July 1759 the British had also taken the impressive stone structure at the French Fort Niagara, where the Niagara River and Niagara Falls rush down into Lake Ontario. On September 13, 1759 the British finally took Quebec – the great citadel of the French empire in America, at the top of a cliff on the St. Lawrence River.

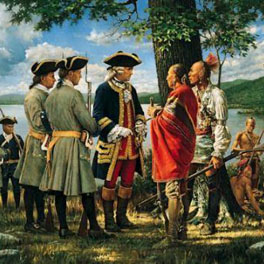

A year later the French might have taken Quebec back, but the British Royal Navy made sure that it was British and not French ships which sailed up the river in the spring, to re-supply British and not French land forces. And then, besieged from three directions by General Jeffrey Amherst, Montreal at last surrendered on September 8, 1760. Major Robert Rogers and his Rangers, who had been on the campaign against Montreal, then set out to take possession of the French fort at Detroit. On his way, he later claimed, Rogers met Pontiac, war chief of the Ottawa.

5. Pontiac’s Rebellion: the gathering storm …

For all practical purposes, the Seven Years War in North America was over by the end of 1760. But it would take another two years to resolve the remaining conflicts among the European powers of the day in such places as Havana, the Philippines, and Europe itself.

For all practical purposes, the Seven Years War in North America was over by the end of 1760. But it would take another two years to resolve the remaining conflicts among the European powers of the day in such places as Havana, the Philippines, and Europe itself.

It was not until the Treaty of Paris, which was signed on February 10, 1763, that the resulting political changes in the North American Great Lakes region were set down on paper. (Though by this point Robert Rogers and others had already taken over almost all the old French outposts in the pays d’en haut on behalf of the British empire.)

Despair of the aboriginal peoples (and French Canadian traders)

As explained by the historian Richard White, “accounts of the pending cession of Canada to England, which reached the pays d’en haut in early 1763 … came, as Captain Simeon Ecuyer at Fort Pitt [formerly Fort Duquesne] put it, as a ‘thunderclap’ to the Indians. According to [George] Croghan, the cession ‘allmost Drove them to Despair’ … The despair and surprise of the Algonquians at the cession was no greater than that of many French-Canadian traders and habitants of the pays d’en haut. Canadians could not fully believe that they had been abandoned.”

It may be easy enough to see why many French Canadians would be full of despair. The fundamental reasons for the despair of their traditional Indian allies remain matters of debate among historians even today.

Parkman’s advancing waves of Anglo-American power

The remarkable New England gentleman scholar Francis Parkman’s Conspiracy of Pontiac from the middle of the 19th century is nowadays a controversial authority. But it still has grains of truth between the lines.

The remarkable New England gentleman scholar Francis Parkman’s Conspiracy of Pontiac from the middle of the 19th century is nowadays a controversial authority. But it still has grains of truth between the lines.

Parkman tells us: “Could the French have maintained their ground, the ruin of the Indian tribes might long have been postponed ; but the victory of Quebec was the signal of their swift decline. Thenceforth they were destined to melt and vanish before the advancing waves of Anglo-American power, which now rolled westward unchecked and unopposed. They saw the danger, and, led by a great and daring champion, struggled fiercely to avert it.”

The Delaware Prophet …

Parkman, Howard Peckham, Richard White, Gordon Mitchell Sayre, Fred Anderson, Gregory Evans Dowd, David Dixon, and virtually everyone else who has ever written about “Pontiac’s Rebellion” or the “Conspiracy of Pontiac” also stress the role of Neolin or the “Delaware Prophet” in preparing the ground during the early 1760s. Neolin lived near the Ohio River, considerably south of Pontiac’s Detroit. But he had a vision from the “Master of Life,” which spoke to the people of the forest at the end of the French and Indian War.

Parkman, Howard Peckham, Richard White, Gordon Mitchell Sayre, Fred Anderson, Gregory Evans Dowd, David Dixon, and virtually everyone else who has ever written about “Pontiac’s Rebellion” or the “Conspiracy of Pontiac” also stress the role of Neolin or the “Delaware Prophet” in preparing the ground during the early 1760s. Neolin lived near the Ohio River, considerably south of Pontiac’s Detroit. But he had a vision from the “Master of Life,” which spoke to the people of the forest at the end of the French and Indian War.

As Richard White has summarized the vision: “Neolin called upon Indians to reform themselves, to cast away European tools and clothes, and to prepare for a world where they would live independently of whites … He had received a vision from heaven, where, he said, there were no whites but only Indians. He preached that the Indians once had direct access to heaven, but since the coming of whites, they had been taught sins and vices that barred their way and diverted them to hell. To regain the ‘Good Road,’ they had to learn to live ‘without any Trade or Connections with ye white people, Clothing & Supporting themselves as their forefathers did.'”

… and Pontiac’s dream of Onontio’s return

All authorities agree that Pontiac made some shrewd used of this Delaware prophecy, in plotting his (or someone’s?) much more down-to-earth designs for the bloody spring and summer of 1763. As Gordon Mitchell Sayre tells us: “Pontiac invoked the Master of Life and the nativist message in his first major speech to the assembled natives and French habitants at [or near] Detroit, delivered on 27 April 1763.” (Coincidentally, 27 April 2009 was when General Motors discontinued Pontiac brand automobiles.) This oration, Sayre goes on, was “the genesis of his ‘conspiracy,’ if such it was … recorded in … a manuscript journal of the siege written in French” and, much later “found hidden in the walls of a French settler’s house.”

All authorities agree that Pontiac made some shrewd used of this Delaware prophecy, in plotting his (or someone’s?) much more down-to-earth designs for the bloody spring and summer of 1763. As Gordon Mitchell Sayre tells us: “Pontiac invoked the Master of Life and the nativist message in his first major speech to the assembled natives and French habitants at [or near] Detroit, delivered on 27 April 1763.” (Coincidentally, 27 April 2009 was when General Motors discontinued Pontiac brand automobiles.) This oration, Sayre goes on, was “the genesis of his ‘conspiracy,’ if such it was … recorded in … a manuscript journal of the siege written in French” and, much later “found hidden in the walls of a French settler’s house.”

Yet Pontiac’s account of the nativist message from the Master of Life was not quite the same as Neolin’s. As Sayre explains, Pontiac had the Master of Life say “‘Whence comes it that ye permit the Whites upon your lands? Can ye not live without them?’ All this is consistent with other accounts of Neolin’s message. But Pontiac then alludes to the Master of Life’s support for the French over the English by … evoking the paternal figure [of Onontio, the old French governor at Quebec]: ‘I do not forbid you to permit among you the children of your Father [Onontio]; I love them … and I supply their wants and all they give you. But as to those who come to trouble your lands [i.e. the British or English or Anglo-Americans] – drive them out, make war upon them … Send them back to the lands which I have created for them and let them stay there.'”

The dynamism of a farming population seeking opportunity

Before the Seven Years War, Pontiac might also have said, the French and British empires in North America were quite different political constructions. The French empire had small numbers of people of European descent, clustered to the east in the St. Lawrence valley (and to a lesser extent around New Orleans), and then a quite vast French and Indian western interior, dominated by the fur trade and the “Janus-faced alliance” between the Algonquian-speaking peoples and “Onontio, the French governor at Quebec.” The British empire had much larger numbers of people of European descent, still clustered along the Atlantic seaboard, but already embarked on an aggressive western settlement frontier, with very little room for the traditional cultures of aboriginal peoples.

As explained by the historian Fred Anderson, “the single most striking , and potentially disruptive, trend” in the old British North America at the end of the French and Indian War was “the rapid movement of colonists and European immigrants into backwoods and newly conquered regions.” The “power that animated the whole system of settlement and speculation, was the dynamism of a farming population seeking opportunity … Only violent resistance by native peoples … could effectively restrain the movements of a population that paid little heed to any contravening laws, boundaries, or policies of the colonial governments.”

Amherst’s mistaken Indian policy in the Great Lakes

As even Francis Parkman recognized, in his own way, there was more room for aboriginal cultures in the traditional structure of the fallen French empire. And this leads to yet another explanation for the rebellion against the British takeover of French America, that broke out among the more westerly aboriginal peoples at the end of the French and Indian War.

As even Francis Parkman recognized, in his own way, there was more room for aboriginal cultures in the traditional structure of the fallen French empire. And this leads to yet another explanation for the rebellion against the British takeover of French America, that broke out among the more westerly aboriginal peoples at the end of the French and Indian War.

Some British North Americans – William Johnson in the Mohawk Valley of the Royal Province of New York is one strong case in point – could see that to ensure peace in its new territories the British empire had to start treating the Indians of the old pays d’en haut much as the French empire had done. But the commanding officer from across the sea, General Jeffrey Amherst, could not grasp this point.

As a financially prudent administrator (and a great believer in militarist solutions to political problems, especially where Indians were involved), Amherst tried to introduce a much less generous Indian policy than Onontio at Quebec city had run.

The Indian allies of the French saw this new British policy in action, at the old French upper country outposts taken over by the British after the surrender of Montreal in September 1760. And Pontiac’s dream that Onontio would return if the Indian allies protested loudly enough, won more and more support among the aboriginal peoples of the still smouldering pays d’en haut.

6. Pontiac’s Rebellion: some walls come tumbling down, 1763

In the 19th century Francis Parkman saw Pontiac as the great mastermind behind the rebellion (or conspiracy) that history still names after him. Historians today are more sceptical – and perhaps realistic – about his role: “The prevailing view … is that, rather than being planned in advance, the uprising spread as word of Pontiac’s actions … traveled throughout the pays d’en haut, inspiring already discontented Natives to join the revolt.”

Pontiac’s siege of Fort Detroit

The definitive news that Onontio actually had surrendered the Great Lakes region to the British empire, at the Treaty of Paris in February 1763, was the ultimate catalyst. As already noted, on “April 27, 1763, Pontiac spoke at a council about 10 miles … below the settlement of Detroit … [u]sing the teachings of Neolin [or the Delaware Prophet] to inspire his listeners.” On May 1, Pontiac visited the now British fort at Detroit with 50 Ottawas in order to assess the strength of the garrison. Then, in what he hoped would be a surprise attack, on May 7 he entered Fort Detroit with about 300 men carrying concealed weapons.

The definitive news that Onontio actually had surrendered the Great Lakes region to the British empire, at the Treaty of Paris in February 1763, was the ultimate catalyst. As already noted, on “April 27, 1763, Pontiac spoke at a council about 10 miles … below the settlement of Detroit … [u]sing the teachings of Neolin [or the Delaware Prophet] to inspire his listeners.” On May 1, Pontiac visited the now British fort at Detroit with 50 Ottawas in order to assess the strength of the garrison. Then, in what he hoped would be a surprise attack, on May 7 he entered Fort Detroit with about 300 men carrying concealed weapons.

The British had learned of the planned surprise (from the native mistress of the fort’s commanding officer, some sources say), “and were armed and ready.” Pontiac withdrew. But two days later, on May 9, he laid siege to the fort. He “and his allies killed all of the British soldiers and settlers they could find outside of the fort, including women and children. One of the soldiers was ritually cannibalized, as was the custom in some Great Lakes Native cultures. The violence was directed at the British; French [Canadian] colonists were generally left alone. Eventually more than 900 warriors from a half-dozen tribes joined the siege.”

Pontiac’s co-conspirators take eight smaller outposts

What happened next helps explain why observers of the day felt they were witnessing a “conspiracy,” planned in some detail by Pontiac himself or perhaps by allied French Canadians:

What happened next helps explain why observers of the day felt they were witnessing a “conspiracy,” planned in some detail by Pontiac himself or perhaps by allied French Canadians:

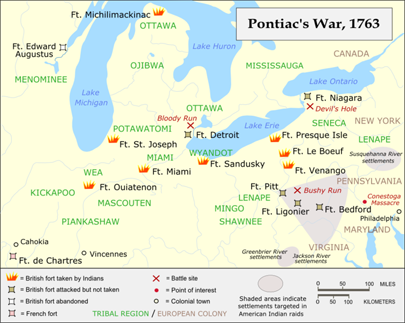

* As at Fort Detroit, all the smaller old French forts in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions had been taken over by British forces during the last two years of the Seven Years War – and some new British outposts had been erected. On May 16, 1763, only a week after Pontiac launched his siege of Detroit, a group of Wyandots took over “Fort Sandusky, a small blockhouse on the shore of Lake Erie … built in 1761 by order of General Amherst … They seized the commander and killed the other 15 soldiers.”

* On May 25 “Fort St. Joseph [present-day Niles, Michigan] was captured … by Potawatomis, and most of the 15-man garrison was killed outright.”

* Two days later, on May 27, the British commander of Fort Miami [on the site of present Fort Wayne, Indiana] “was lured out of the fort by his Native mistress and shot dead by Miami Natives. The nine-man garrison surrendered after the fort was surrounded.”

* On June 1 Fort Ouiatenon in the Illinois Country, [about 5 miles (8.0 km) southwest of today’s Lafayette, Indiana] was taken by Weas, Kickapoos, and Mascoutens.

* The next day, June 2, local Ojibwas much further north staged a lacrosse game with visiting Sauks at Fort Michilimackinac [the present Mackinaw City, Michigan]. The British soldiers “watched the game, as they had done on previous occasions. The ball was hit through the open gate of the fort; the teams rushed in and were then handed weapons which had been smuggled into the fort by Native women.”

* Back down south, around June 16, Fort Venango [near the present Franklin, Pennsylvania] was taken by Senecas (the most westerly and sometimes pro-French of the usually pro-English Six Nations Iroquois of New York): “The entire 12-man garrison was killed outright, except for the commander, who was made to write down the grievances of the Senecas” against the British, and then “burned at the stake.”

* Back down south, around June 16, Fort Venango [near the present Franklin, Pennsylvania] was taken by Senecas (the most westerly and sometimes pro-French of the usually pro-English Six Nations Iroquois of New York): “The entire 12-man garrison was killed outright, except for the commander, who was made to write down the grievances of the Senecas” against the British, and then “burned at the stake.”

* On June 18 Fort Le Boeuf [today’s Waterford, Pennsylvania] “was attacked … possibly by the same Senecas who had destroyed Fort Venango. Most of the 12-man garrison escaped to Fort Pitt” (the former Fort Duquesne, renamed after the British Prime Minister William Pitt [the Elder]).

* Finally, on the night of June 19 Fort Presque Isle [today’s Erie, Pennsylvania] was surrounded by about 250 Ottawas, Ojibwas, Wyandots, and Senecas: “After holding out for two days, the garrison of about 30 to 60 men surrendered on the condition that they could return to Fort Pitt. Most were instead killed after emerging from the fort. ”

Battle of Bloody Run and lifting of siege at Fort Detroit

It is true enough that all eight forts taken by Pontiac’s Rebellion between May 16 and June 19 in 1763 were little more than small wilderness outposts. (Fort Michilimackinac was the closest to something more substantial.) Pontiac’s own siege of the much more major establishment at Fort Detroit carried on, but the British still held the fort.

It is true enough that all eight forts taken by Pontiac’s Rebellion between May 16 and June 19 in 1763 were little more than small wilderness outposts. (Fort Michilimackinac was the closest to something more substantial.) Pontiac’s own siege of the much more major establishment at Fort Detroit carried on, but the British still held the fort.

In the middle of the summer the British attempted a surprise attack on Pontiac’s encampment. But he was ready and waiting, and defeated them at the Battle of Bloody Run on July 31, 1763. With the more than 900 warriors ultimately at his command, Pontiac almost certainly could have taken the fort if he had stormed it head on. But this would have entailed much more loss of life among the attackers than the democratic norms of aboriginal warfare would tolerate.

As the leaves began to fall, “Pontiac’s influence among his followers began to wane. Groups of Natives began to abandon the siege, some of them making peace with the British before departing.” At the end of October 1763, Pontiac received definitive word that French forces still in the Illinois Country (which, west of the Mississippi River, was finally to be handed over to the King of Spain, under the terms of the Peace of Paris) would not come to his aid at Detroit.

Pontiac then”lifted the siege and removed to the Maumee River” for the winter, where he nonetheless “continued his efforts to rally resistance against the British.” Yet even here, as the historian Fred Anderson has urged: “No one in the Indian camp knew it, but on the day Pontiac finally offered a truce, Detroit had less than two weeks’ supply of flour remaining. And no prospect of replenishment.” Had Pontiac only held on for another three weeks, into late November 1763, he might have starved the British forces at Fort Detroit into submission!

The siege of Fort Pitt (and the legend of the smallpox war)

Back somewhat east and to the south, a similar fate had by this point befallen the old French Fort Duquesne, a re-furbished version of which the British now occupied as Fort Pitt (in downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania today). Another feature of Pontiac’s (or whoever’s or whatever’s) Rebellion in the spring of 1763 was Indian raids on the most westerly reaches of the Anglo-American settlement frontier in Virginia and Pennsylvania. As a result: “Colonists in western Pennsylvania fled to the safety of Fort Pitt after the outbreak of [Pontiac’s] war.”

Back somewhat east and to the south, a similar fate had by this point befallen the old French Fort Duquesne, a re-furbished version of which the British now occupied as Fort Pitt (in downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania today). Another feature of Pontiac’s (or whoever’s or whatever’s) Rebellion in the spring of 1763 was Indian raids on the most westerly reaches of the Anglo-American settlement frontier in Virginia and Pennsylvania. As a result: “Colonists in western Pennsylvania fled to the safety of Fort Pitt after the outbreak of [Pontiac’s] war.”

Nearly 550 people “crowded inside, including more than 200 women and children. Simeon Ecuyer, the Swiss-born British officer in command, wrote that ‘We are so crowded in the fort that I fear disease the smallpox is among us.’ Fort Pitt was attacked on June 22, 1763, primarily by Delawares. Too strong to be taken by force, the fort was kept under siege throughout July. Meanwhile, Delaware and Shawnee war parties raided deep into Pennsylvania, taking captives and killing unknown numbers of settlers.”

It was in this context that General Jeffrey Amherst made his notorious proposal to “Colonel Henry Bouquet at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who was preparing to lead an expedition to relieve Fort Pitt.” Amherst asked Bouquet: “Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians?”

As it happened, “officers at the besieged Fort Pitt had already attempted to do what Amherst and Bouquet were still discussing … During a parley … on June 24, 1763, Ecuyer gave representatives of the besieging Delawares two blankets and a handkerchief that had been exposed to smallpox, hoping to spread the disease to the Natives in order to end the siege … Because many Native Americans died from smallpox during Pontiac’s Rebellion, historian Francis Jennings concluded that the attempt was unquestionably effective.’ However, some subsequent scholars have raised doubts about whether the smallpox outbreak can be traced to blankets from Fort Pitt with certainty.”

Battle of Bushy Run

On August 1, 1763 most of the Natives broke off the siege at Fort Pitt in order to intercept 500 British troops marching to the fort under Colonel Bouquet. On August 5, these two forces met at the Battle of Bushy Run. Although his force suffered heavy casualties, Bouquet fought off the attack and relieved Fort Pitt on August 20, bringing the siege to an end.

Yet again Fred Anderson has urged: “When the battle ended Bouquet’s men were able to move to Bushy Run for water, but that was all. They had lost … a quarter of their strength. The Indians had destroyed so many horses that Bouquet ordered the entire stock of flour destroyed in order to use the surviving animals to carry the wounded to Fort Pitt … Like Detroit, Pittsburgh survived the winter of 1763—1764 not because the British had broken the Indians’ siege but because the Indians, no longer able to delay the winter’s hunting, had lifted it.”

Devil’s Hole Massacre

The third great military outpost in the Great Lakes-OhioValley region of the day was the impressive stone fortress that the French had originally erected at Fort Niagara, where the Niagara River rushes into Lake Ontario on its steep downhill journey from Lake Erie. The British also remained in command of this imposing structure throughout Pontiac’s Rebellion.

The third great military outpost in the Great Lakes-OhioValley region of the day was the impressive stone fortress that the French had originally erected at Fort Niagara, where the Niagara River rushes into Lake Ontario on its steep downhill journey from Lake Erie. The British also remained in command of this imposing structure throughout Pontiac’s Rebellion.

But “on September 14, 1763, at least 300 Senecas, Ottawas, and Ojibwas attacked a supply train along the Niagara Falls portage [between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario – a crucial linkage in the pioneer transportation network from both Montreal and New York to Detroit and many other points west]. Two companies sent from Fort Niagara to rescue the supply train were also defeated. More than 70 soldiers and teamsters were killed in these actions, which Anglo-Americans called the ‘Devil’s Hole Massacre,’ the deadliest engagement for British soldiers during the war.”

The Royal Proclamation of 1763

As another early sign that the old Indian allies of Onontio were not exactly losing the rebellion: “On October 7, 1763, the [British] Crown issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, an effort to reorganize British North America after the Treaty of Paris. The Proclamation, already in the works when Pontiac’s Rebellion erupted, was hurriedly issued after news of the uprising reached London.”

In the Proclamation: “Officials drew a boundary line between the British colonies along the seaboard and Native American lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, creating a vast ‘Indian Reserve’ that stretched from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. By forbidding colonists from trespassing on Native lands, the British government hoped to avoid more conflicts like Pontiac’s Rebellion.”

7. Pontiac’s Rebellion: denouement 1764-1766 …

For future relations between the British imperial officialdom in London and the Anglo-Americans in the Thirteen Colonies the Royal Proclamation of 1763 would prove a flawed document. As Fred Anderson has urged, however, the British government also or especially saw the Proclamation “as a first step toward placing Indian relations on a firm foundation.” And it was more constructive in this context.

As another step in the same direction, General Jeffrey Amherst, “was recalled to London in August 1763 and replaced by Major General Thomas Gage. In 1764, Gage sent two expeditions into the west to crush the rebellion, rescue British prisoners, and arrest the Natives responsible for the war.” Yet, again, according to Fred Anderson, “Gage’s campaign, which had been designed by Amherst, prolonged the war for more than a year because it focused on punishing the Natives rather than ending the war.”

The Paxton boys … and more Indian raids on frontier settlements

Another ingredient in the prolonged denouement of Pontiac’s Rebellion was a wild backlash at the edges of the western frontier, which helped prompt further Indian attacks on new pioneer settlements. To start with, late in 1763 a vigilante group of Anglo-Americans incensed by earlier Indian raids came together in the area around the Pennsylvania village of Paxton. They “turned their anger towards Native Americans-many of them Christians – who lived peacefully in small enclaves in the midst of white Pennsylvania settlements.”

Another ingredient in the prolonged denouement of Pontiac’s Rebellion was a wild backlash at the edges of the western frontier, which helped prompt further Indian attacks on new pioneer settlements. To start with, late in 1763 a vigilante group of Anglo-Americans incensed by earlier Indian raids came together in the area around the Pennsylvania village of Paxton. They “turned their anger towards Native Americans-many of them Christians – who lived peacefully in small enclaves in the midst of white Pennsylvania settlements.”

A few weeks before Christmas there were (almost certainly false?) rumours that a war party had been seen at the Susquehannock village of Conestoga. On December 14, 1763 more than 50 so-called Paxton Boys “marched on the village and murdered the six Susquehannocks they found there. Pennsylvania officials placed the remaining 14 Susquehannocks in protective custody in Lancaster, but on December 27 the Paxton Boys broke into the jail and slaughtered them. ”

The Paxton Boys “then set their sights on other Natives living within eastern Pennsylvania, many of whom fled to Philadelphia for protection. Several hundred Paxtonians marched on Philadelphia in January 1764, where the presence of British troops and Philadelphia militia prevented them from doing more violence.” Benjamin Franklin “negotiated with the Paxton leaders and brought an end to the immediate crisis.” (He subsequently “published a scathing indictment of the Paxton Boys. ‘If an Indian injures me,’ he asked, ‘does it follow that I may revenge that Injury on all Indians?””)

These Paxtonian adventures may also help explain why “Native American raids on frontier settlements escalated in the spring and summer of 1764.” The “hardest hit colony that year was Virginia, where more than 100 settlers were killed.” At the same time: “On May 26 in Maryland, 15 colonists working in a field near Fort Cumberland were killed. On June 14, about 13 settlers near Fort Loudoun in Pennsylvania were killed and their homes burned. The most notorious raid occurred on July 26, when four Delaware warriors killed and scalped a school teacher and ten children in what is now Franklin County, Pennsylvania.”

William Johnson’s first peace treaty of 1764 …

As already alluded to, yet another ingredient in the prolonged denouement was the tendency of the new British commander in British North America, Major General Thomas Gage, to follow too closely in the unsuccessful policy footsteps of his predecessor General Jeffrey Amherst. But “Gage’s one significant departure from Amherst’s plan[s] was to allow William Johnson [from the Mohawk Valley in New York] to conduct a peace treaty at Niagara, giving those Natives who were ready to ‘bury the hatchet’ a chance to do so.”

As already alluded to, yet another ingredient in the prolonged denouement was the tendency of the new British commander in British North America, Major General Thomas Gage, to follow too closely in the unsuccessful policy footsteps of his predecessor General Jeffrey Amherst. But “Gage’s one significant departure from Amherst’s plan[s] was to allow William Johnson [from the Mohawk Valley in New York] to conduct a peace treaty at Niagara, giving those Natives who were ready to ‘bury the hatchet’ a chance to do so.”

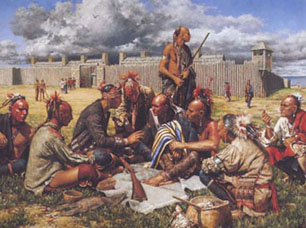

From July to August 1764 “Johnson negotiated a treaty at Fort Niagara with about 2,000 Natives … primarily Iroquois. Although most Iroquois had stayed out of [Pontiac’s] war, Senecas from the Genesee River valley had taken up arms against the British, and Johnson worked to bring them back into the Covenant Chain alliance. As restitution for the Devil’s Hole ambush, the Senecas were compelled to cede the strategically important Niagara portage to the British. Johnson even convinced the Iroquois to send a war party against the Ohio Natives. This Iroquois expedition captured a number of Delawares and destroyed abandoned Delaware and Shawnee towns in the Susquehanna Valley, but otherwise the Iroquois did not contribute to the war effort as much as Johnson had desired.”

The Bradstreet and Bouquet expeditions …

Before he left for Britain in the summer of 1763 General Amherst had drawn up plans for two military expeditions to pacify the still smouldering Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions, during the spring and summer of 1764. These plans were finally brought to at least certain versions of life under the broad supervision of Major General Gage.

Before he left for Britain in the summer of 1763 General Amherst had drawn up plans for two military expeditions to pacify the still smouldering Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions, during the spring and summer of 1764. These plans were finally brought to at least certain versions of life under the broad supervision of Major General Gage.

The first “northern” expedition, led by Colonel John Bradstreet, was to travel by boat across Lake Erie and “subdue the Natives around Detroit before marching south into the Ohio Country.” A second “southern” foray, commanded by Colonel Bouquet, “was to march west from Fort Pitt and form a second front in the Ohio Country.”

Bradstreet set out in early August 1764 with about 1,200 soldiers and a large contingent of Indian allies enlisted by William Johnson. On August 12 strong winds on Lake Erie forced him to stop at Presque Isle, where he negotiated what he mistakenly thought was a peace treaty with a delegation from the Ohio Valley. He then continued westward, reaching Fort Detroit on August 26. Here he negotiated a less ambiguous treaty, but destroyed a peace belt Pontiac had sent in lieu of appearing in person: “Although Bradstreet had successfully reinforced and reoccupied British forts in the region, his diplomacy proved to be controversial and inconclusive.”

Colonel Bouquet was delayed by trouble mustering militia in Pennsylvania, but he set out at last from Fort Pitt on October 3, 1764, with 1,150 men. He marched to the Muskingum River in the Ohio Country, close to a number of native villages. By this point the Ohio Indians were apparently ready to make a more serious peace agreement than the one Bradstreet thought he had made in August. In a council which began on 17 October, Bouquet laid some solid groundwork for a more formal agreement that William Johnson would finalize in July 1765.

William Johnson’s treaty with Pontiac in 1766 …

Despite their ambiguities, the Bradstreet and Bouquet expeditions of 1764 largely ended Indian-European military conflict in the lower Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions, for the time being at least. Yet, further west: “Natives still called for resistance in the Illinois Country, where British troops had yet to take possession of Fort de Chartres from the French.”

Despite their ambiguities, the Bradstreet and Bouquet expeditions of 1764 largely ended Indian-European military conflict in the lower Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions, for the time being at least. Yet, further west: “Natives still called for resistance in the Illinois Country, where British troops had yet to take possession of Fort de Chartres from the French.”

A “Shawnee war chief named Charlot Kaské emerged as the most strident anti-British leader in the [Illinois] region, temporarily surpassing Pontiac in influence. Kaské travelled as far south as New Orleans in an effort to enlist French aid against the British.” (Moreover: “Kaské’s personal details were unusual for a Shawnee chief: he was a Catholic, his father was German, and his wife was an English captive brought up among the Shawnees.”)

In this setting British officials acquired some final fresh interest in Pontiac, who, while moving increasingly further west himself, had also “become less militant after hearing of Bouquet’s truce with the Ohio Country Natives.” George Croghan, now among other things a deputy of William Johnson’s, travelled west and finally “managed to meet and negotiate with Pontiac.”

In this setting British officials acquired some final fresh interest in Pontiac, who, while moving increasingly further west himself, had also “become less militant after hearing of Bouquet’s truce with the Ohio Country Natives.” George Croghan, now among other things a deputy of William Johnson’s, travelled west and finally “managed to meet and negotiate with Pontiac.”

Charlot Kaské “wanted to burn Croghan at the stake,” but Pontiac “urged moderation and agreed to travel to New York, where he made a formal treaty with William Johnson at Fort Ontario [or Oswego] on July 25, 1766. It was hardly a surrender: no lands were ceded, no prisoners returned, and no hostages were taken. Rather than accept British sovereignty, Kaské left British territory by crossing the Mississippi River [into what was now a new part of the old Louisiana, whose European master was the King of Spain] with other French and [Indian] refugees.”

8. Death of Pontiac at Cahokia, 1769 …

Whatever Pontiac’s actual role had been in the early days of the rebellion or conspiracy named after him, during the bloody spring and summer of 1763, by the late 1760s he was a diminished figure in the eyes of many of his contemporaries. The simplest truth may be that he at least helped inspire a great struggle which, if it did not exactly fail in the end, was far from a great success. And the destiny of such leaders is seldom a happy one in their own time.

Whatever Pontiac’s actual role had been in the early days of the rebellion or conspiracy named after him, during the bloody spring and summer of 1763, by the late 1760s he was a diminished figure in the eyes of many of his contemporaries. The simplest truth may be that he at least helped inspire a great struggle which, if it did not exactly fail in the end, was far from a great success. And the destiny of such leaders is seldom a happy one in their own time.

Historians have told various tales of Pontiac’s ultimate fate. Fred Anderson’s is among the most recent: “Seduced by the illusion that British support would enable him to lead many nations, he became only the focus of other leaders’ resentments … By the spring of 1768 the young men of his own village were making such sport of him that to save himself from their casual beatings he withdrew to live among his wife’s relatives in the Illinois Country. There, more isolated than ever, he lost even the ability to defend himself. On April 20, 1769, a Peoria warrior clubbed him senseless, then stabbed him to death in front of Baynton, Wharton and Morgan’s trading post at Cahokia, on the Mississippi shore opposite St. Louis. No one – not even his own sons – felt obliged to avenge Pontiac’s murder.”

Anderson’s notes suggest that his story here draws on two seminal publications of the 20th century: Howard Peckham’s Pontiac and the Indian Uprising (1947) and Richard White’s The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650—1815 (1991). Francis Parkman’s 19th century classic, The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada (1851), told a rather different story. As explained by the current Wikipedia article on “Chief Pontiac,” in Parkman’s pages “a terrible war of retaliation against the Peorias resulted from Pontiac’s murder. Although this legend is still sometimes repeated, there is no evidence that there were any reprisals for Pontiac’s murder.”

Parkman himself allowed that “tradition has but faintly preserved the memory of the event; and its only annalists, men who held the intestine feuds of the savage tribes in no more account than the quarrels of panthers or wildcats, have left but a meagre record.” Yet in the final pages of his Conspiracy of Pontiac, Parkman also offered another intriguing tale of Pontiac’s last days, which may rest on somewhat firmer ground.

Some time after Pontiac arrived in the Illinois Country, Parkman tells us, “he repaired to St. Louis [on the west bank of the Mississippi, which had been assigned to Spain in the Treaty of Paris], to visit his former acquaintance Saint-Ange, who was then in command at that post, having offered his services to the Spaniards after the cession of Louisiana. After leaving the fort, Pontiac proceeded to the house of which young Pierre Chouteau was an inmate; and to the last days of his protracted life, the latter could vividly recall the circumstances of the interview.”

Some time after Pontiac arrived in the Illinois Country, Parkman tells us, “he repaired to St. Louis [on the west bank of the Mississippi, which had been assigned to Spain in the Treaty of Paris], to visit his former acquaintance Saint-Ange, who was then in command at that post, having offered his services to the Spaniards after the cession of Louisiana. After leaving the fort, Pontiac proceeded to the house of which young Pierre Chouteau was an inmate; and to the last days of his protracted life, the latter could vividly recall the circumstances of the interview.”

Parkman goes on: “The savage chief was arrayed in the full uniform of a French officer, which had been presented to him as a special mark of respect and favor by the Marquis of Montcalm, towards the close of the French war, and which Pontiac never had the bad taste to wear, except on occasions when he wished to appear with unusual dignity.”

Following his visit to Chouteau, Pontiac “remained at St. Louis for two or three days, when, hearing that a large number of Indians were assembled at Cahokia, on the opposite side of the river, and that some drinking bout or other social gathering was in progress, he told Saint-Ange that he would cross over to see what was going forward … He entered a canoe with some of his followers, and Chouteau never saw him again.”

(The current Wikipedia article on “Chief Pontiac” adds: “Pontiac’s burial place is unknown, and may have been at Cahokia, but evidence and tradition suggest that he was buried in St. Louis. In 1900, a plaque was mounted in a hallway of the Southern Hotel, which had been built over the reputed gravesite in 1890.”)

9. Pontiac and Canada after La Conquête

Pontiac’s death in the Mississippi Valley – quite far from Detroit, to say nothing of Montreal and Quebec – can obscure the continuing impact of his fierce protest against what Francis Parkman in the 19th century called the “Conquest of Canada.”

Pontiac’s death in the Mississippi Valley – quite far from Detroit, to say nothing of Montreal and Quebec – can obscure the continuing impact of his fierce protest against what Francis Parkman in the 19th century called the “Conquest of Canada.”

What Richard White calls the “reduced modern Pontiacs” of Howard Peckham and his successors “conform better to the facts” than Parkman’s more heroic (if also vaguely “racialist”) Pontiac. But they also, White urges, “distort his context, mistake the nature of his failure, and miss his success.” It is a measure of Pontiac’s success – or at least the success of the rebellion which history has named after him – that Canada survives as a “bilingual and multicultural” country in the early 21st century.

(Canada today has still not altogether decolonized or quite grown up. But it is an independent member of the United Nations, and one of the three sovereign signatories of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Its Constitution Act 1982 recognizes the rights of “the aboriginal peoples of Canada.” The French-speaking Québécois remain, as the federal parliament in Ottawa declared late in 2006, a “nation within a united Canada” – and the unique province of Quebec is still part of the Canadian confederation of 1867.)

(Canada today has still not altogether decolonized or quite grown up. But it is an independent member of the United Nations, and one of the three sovereign signatories of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Its Constitution Act 1982 recognizes the rights of “the aboriginal peoples of Canada.” The French-speaking Québécois remain, as the federal parliament in Ottawa declared late in 2006, a “nation within a united Canada” – and the unique province of Quebec is still part of the Canadian confederation of 1867.)

Both Richard White and Fred Anderson have things to say that further illuminate this Canadian side of the Pontiac story. As explained by White, e.g., in the end Pontiac “rose against the British to restore his French father and created a British father instead.” Or, “Pontiac’s Rebellion was almost the reverse of the ultimate racial showdown Parkman imagined … Out of the radically different British and Algonquian interpretations of the meaning of the British victory over the French, it forged a new, if tenuous accommodation … The British replaced the French as fathers … Pontiac, in his attempt to kill the British, helped to turn them into fathers.”

With William Johnson’s final treaty at Oswego on July 25, 1766, the vast ironies of the last French and Indian War, on both the British and Algonquian sides, set in. The aboriginal policy of the old French American empire, broadly hinted at in the Royal Proclamation of 1763, was revived. And Pontiac, Richard White tells us, “after initiating a revolt to restore his French father … accepted the British king as his father.”

Once William Johnson had been able to abandon earlier British “claims of absolute sovereignty over the Indians, the political contours” of what Richard White has influentially called the 18th century “middle ground” between Indians and Europeans “remained basically the same as in the French era. The Algonquians became allied with the British, and the British king became the father of the Algonquians.” More practically, the “British tried to demonstrate their ‘love’ for their children by allocating twenty thousand pounds annually for presents and contingent expenses in North America,” in a new effort to “meet expectations raised by French practices.”

Fred Anderson plays his own variations on similar themes. Finally, with William Johnson on Lake Ontario in the summer of 1766 – and unlike Charlot Kaské who “followed the French across the [Mississippi] river in the fall of 1765,” Pontiac accepted “a British father in the stead of Onontio, who would never wake again.”

Fred Anderson plays his own variations on similar themes. Finally, with William Johnson on Lake Ontario in the summer of 1766 – and unlike Charlot Kaské who “followed the French across the [Mississippi] river in the fall of 1765,” Pontiac accepted “a British father in the stead of Onontio, who would never wake again.”

Moreover, Anderson urges, at “the peak of its success” the old French empire in America “had been less a French dominion than a multicultural confederation knit together by diplomacy , trade, and the necessity of defending against English aggression.” And Pontiac’s Rebellion meant that the British didn’t so much conquer as assume responsibility for the future of this confederation: “The Peace of Paris obliged George III to extend his protection to his new subjects, Indian and French alike, and he and his ministers (as the Proclamation of 1763 attested) took this obligation quite seriously.”

At the same time, Anderson reminds us, in the British King’s own original American empire “British colonists focused their attention on acquiring land from native peoples rather than trading with them.” And so “Britain’s empire had not developed into the kind of expansive multicultural community France’s had; instead, English settlers explicitly predominated in the British colonies, exercising political, economic, and social hegemony with the backing of an otherwise detached king in Parliament.”

And so, a mere dozen years after the signing of the Treaty of Paris in February 1763 the Seven Years War in North America, and the subsequent aboriginal rebellion against the so-called British conquest of Canada (which was really more of a corporate takeover), all too quickly led to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War or War of Independence, at Lexington, Massachusetts on the fateful morning of April 19, 1775.

On an older colonial theory, it was the northern migrations of British empire loyalists from the new United States, at the end of the Revolutionary War in the mid 1780s, that gave birth to the modern anglophone-majority Canada of today. A newer, more historically apt and decolonized theory began to arise at the hands of the same still compelling fur-trade historian Harold Innis, who declared back in 1930: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.”

On an older colonial theory, it was the northern migrations of British empire loyalists from the new United States, at the end of the Revolutionary War in the mid 1780s, that gave birth to the modern anglophone-majority Canada of today. A newer, more historically apt and decolonized theory began to arise at the hands of the same still compelling fur-trade historian Harold Innis, who declared back in 1930: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.”

By the end of what Innis called “the Pontiac wars,” new English-speaking merchants (often from the old British America) had begun to re-shape Onontio’s French-Algonquian fur-trade alliance into a more up-to-date British North American corporate organization, that would take the historic Indian-European fur trade in Canada all the way from the Atlantic to the Arctic and Pacific oceans by the end of the 18th century.

Following “a 16-share organization formed in 1779,” the new corporate entity known as “the North West Company was officially created, with its corporate offices on Vaudreuil Street in Montreal” in 1783 – the year when the American Revolutionary War came to an end. This North West Company, Harold Innis also urged in 1930, was the real ” forerunner of [the Canadian] confederation [of 1867], and it was built on the work of the French voyageur, the contributions of the Indian, especially the canoe, Indian corn, and pemmican, and the organizing ability of Anglo-American merchants.”

Following “a 16-share organization formed in 1779,” the new corporate entity known as “the North West Company was officially created, with its corporate offices on Vaudreuil Street in Montreal” in 1783 – the year when the American Revolutionary War came to an end. This North West Company, Harold Innis also urged in 1930, was the real ” forerunner of [the Canadian] confederation [of 1867], and it was built on the work of the French voyageur, the contributions of the Indian, especially the canoe, Indian corn, and pemmican, and the organizing ability of Anglo-American merchants.”

The later 20th and early 21st centuries have brought some dazzling fresh depth to Fred Anderson’s “multicultural confederation” of the old French and Indian Canada in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is no doubt highly unlikely that Pontiac, war chief of the Ottawa, had any kind of notion that he was fighting for the multicultural confederation of Canada today. It is nonetheless one of his legacies. History, as the Anglo-American poet from St. Louis has told us, “has many cunning passages, contrived corridors / And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions, / Guides us by vanities … Virtues / Are forced upon us by our impudent crimes. / These tears are shaken from the wrath-bearing tree.”

10. L’envoi: what’s good for General Motors is good for the USA … and Canada too?

Nothing stays the same forever. And being bankrupt of history – as the historian Jill Lepore urges we are in North America today – impoverishes our understanding of what is happening to us in the present. To the apparent puzzlement of at least many in the United States (on the rare occasions they think about such things, of course), Canada and the United States remain politically separate in the early 21st century, just as they were in the middle of the 18th century. But both places have evolved since the end of the American Revolutionary War and the establishment of the North West Company in 1783.

Nothing stays the same forever. And being bankrupt of history – as the historian Jill Lepore urges we are in North America today – impoverishes our understanding of what is happening to us in the present. To the apparent puzzlement of at least many in the United States (on the rare occasions they think about such things, of course), Canada and the United States remain politically separate in the early 21st century, just as they were in the middle of the 18th century. But both places have evolved since the end of the American Revolutionary War and the establishment of the North West Company in 1783.

Fred Anderson concludes his recent book on the Seven Years War in North America with helpful thoughts on the subsequent evolution of the United States. When it began, the new American republic was “not the kind of expansive multicultural community” that Canada had developed into under the old French imperial regime. The new United States was still, like the old British Thirteen Colonies, a place where “English settlers explicitly predominated … exercising political, economic, and social hegemony.”

Yet the United States had also “begun by grounding its institutions in statements of principle and fundamental law that defined rights so broadly that any man – or even woman – who aspired to become a member of the body politic might plausibly claim to be entitled to them, on the mere grounds of his or her humanity. That such claims would be automatically honored was not what mattered most, but rather that they would become the basis of repeated struggles for enfranchisement. Those struggles would become the distinguishing feature of American history, leading to a second revolutionary upheaval in the 1860s and reverberating in our public life down to this day.”

Yet the United States had also “begun by grounding its institutions in statements of principle and fundamental law that defined rights so broadly that any man – or even woman – who aspired to become a member of the body politic might plausibly claim to be entitled to them, on the mere grounds of his or her humanity. That such claims would be automatically honored was not what mattered most, but rather that they would become the basis of repeated struggles for enfranchisement. Those struggles would become the distinguishing feature of American history, leading to a second revolutionary upheaval in the 1860s and reverberating in our public life down to this day.”

Similarly, in the Canada that became the new British North America after the American Revolutionary War something of the old political, economic, and social hegemony of English settlers in the former British Thirteen Colonies did seep across the north-south border that would be defended militarily one last time in the War of 1812-1814.

And in yet another of the many vast ironies of Canadian history, in the later 20th century Pierre Trudeau (a kind of descendant of Pontiac, in some respects) at last gave Canada its own version of “statements of principle and fundamental law that defined rights so broadly that any man – or even woman – who aspired to become a member of the body politic might plausibly claim to be entitled to them” – in a (so far even surprisingly successful?) effort to reinvigorate the ancient multicultural confederation with which Canada began.

Similarly again, in a development that even Fred Anderson probably did not anticipate when his book on the Seven Years War was first published in the year 2000, the election of Barack Obama as president of the United States in 2008 confirmed that the reverberating struggles for enfranchisement into the USA’s own original statements of principle and fundamental law have now reached a point where the American republic has at last become its own kind of multicultural community in North America.

Similarly again, in a development that even Fred Anderson probably did not anticipate when his book on the Seven Years War was first published in the year 2000, the election of Barack Obama as president of the United States in 2008 confirmed that the reverberating struggles for enfranchisement into the USA’s own original statements of principle and fundamental law have now reached a point where the American republic has at last become its own kind of multicultural community in North America.

Canada and the United States remain separate countries. The now long undefended border between the two places is at the moment growing thicker not thinner, in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist disaster. Canada still has far fewer people than the United States. But it is geographically somewhat larger, still full of valuable natural resources (including oil), and it somehow manages to survive. The second official language of Canada is French, and the second almost official language of the United States is at least rapidly becoming Spanish. One way or another, the legacy of the historical Pontiac who was the war chief of the Ottawa lives on.

At the same time, the United States and Canada today are also closer than they have ever been before. This is partly because all “free and democratic societies” around the world (to use the language of Pierre Trudeau’s Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada’s Constitution Act 1982) are closer than they have ever been before. But it is also because the United States and Canada continue to share some unique continental destiny (which probably ultimately does include Mexico as well, as the North American Free Trade Agreement makes clear).

Pontiac the 18th century war chief of the Ottawa is finally a figure of interest and importance in the histories of both Canada and the United States. And this ultimately takes us back to the story of Pontiac the North American automobile, in the early 21st century.

Pontiac the 18th century war chief of the Ottawa is finally a figure of interest and importance in the histories of both Canada and the United States. And this ultimately takes us back to the story of Pontiac the North American automobile, in the early 21st century.