Look what’s happening to Pierre Berton’s Canadian National Dream in 2021

Apr 25th, 2021 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

SPECIAL FROM RANDALL WHITE, FERNWOOD PARK, TORONTO, APRIL 25, 2021. Pierre Berton published his two-volume history of the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the early 1970s – The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (1970) and The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (1971).

I think there are good and bad things to be said about the remarkable Canadian public career of Pierre Berton (1920—2004). And his work in print and on TV was certainly part of the city of Toronto universe in which I grew up in the 1950s and 1960s.

In 2021 I would myself not stress the good things as much as the historian A.B. McKillop in “Books, Brands, and Berton” (The Underhill Review, Fall 2009). But I also think this piece offers a good short sketch of the remarkable career itself.

To me the bad things turn around Pierre Berton’s ultimate failure to concoct what McKillop might call a Canadian brand that could stand up to the harsh new challenges of the 21st century.

Remembering Canada and Louisiana in the first half of the 18th century

To start with, there is the US reviewer of The Great Railway who rather darkly wondered : “What kind of country has a railway for its national dream?” (Even if I can’t quite trace the source for this apt remark at the moment!)

More importantly, Canada today is an increasingly complex place, working hard to deal with increasingly complex forces from outside (and inside). Pierre Berton’s Canadian brand finally proved too simple – not at all complex, cunning, and ironic enough to handle what Marshall McLuhan’s global village (and the USA next door) have now started to become.

The complex point is not a dream about a railway. When Pierre Berton was three years old in the Yukon a 29-year-old Harold Innis at the University of Toronto published A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway (a revision of his PhD thesis for the University of Chicago).

The CPR opened Innis’s eyes to the east-west economic geography first mobilized by the first Canadian resource economy of the northern transcontinental fur trade. In 1930 he published his still-in-print classic, The Fur Trade in Canada : An Introduction to Canadian Economic History.

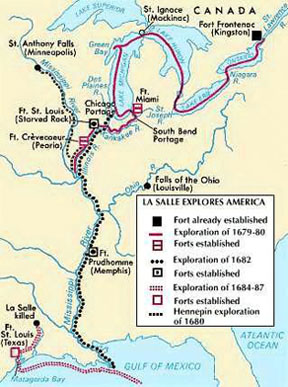

One complex point about Canada’s historic east-west railways is that the earlier fur trade itself evolved in a continental context that included a southern trade in French Louisiana. In the spring of 1682, 74 years after the founding of Quebec City in 1608, René Robert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle and Henri Tonti (and various Algonkian and other First Nations guides and adventurers) travelled vast interior waterways from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, via the Indigenous transportation technology of canoe and portage.

La Salle rather extravagantly claimed all the territory they passed through for Louis XIV, the Sun King of France. And Canada (“We the North”) became only one of the two geographically largest parts of the French American (and allied “Indian”) empire at its height, in the first half of the 18th century.

The other part was the southwestern territory that followed the Mississippi River, and had its capital at La Nouvelle Orl̩ans (founded in 1718). It was known as Louisiana (after Louis XIV) Рbut was much vaster than the present US state of that name.

It would finally be purchased from Napoleon by Thomas Jefferson for the new United States in 1803, having just been returned to France, after a long sojourn with the King of Spain. (Even if the still dominant indigenous First Nations largely ignored such global political subtleties!)

Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway

So much for ancient economic history – with one exception.

By the early 20th century (and thanks in some degree to investment-hungry, newly prosperous members of lower-upper-middle and related classes in the United Kingdom) Canada had not just one but at least three transcontinental east-west railways.

By the end of the First World War (1914—1918) it was clear that even with the dramatic population growth led by the rise of the Last Best North American West on the Canadian Prairie, Canada did not really need three transcontinental railways.

In 1923 William Lyon Mackenzie King’s new Liberal federal government, enlarging on earlier actions, finished buying out the financially hard-pressed competitors of the original Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), and organized their main assets as a new public enterprise called Canadian National Railway (CNR).

Now, fastforward to January 1, 1994 when “The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed by [Canadian] Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Mexican President Carlos Salinas, and US President George HW Bush” took legal effect.

In 1995 Jean Chrétien’s (and finance minister Paul Martin’s) new Liberal federal government privatized Canadian National Railway (to help prepare for the new continental free trade?).

At the same time, the CNR head office remained in Montreal – traditional metropolis of the first resource economy of the transcontinental fur trade (and Canada’s most populous metropolitan region until 1976, when that title moved to Toronto, for who knows how long).

Logically enough the CPR had also been headquartered in the Montreal fur- trade metropolis from the very start. As another response to late 20th century winds of change in the Canadian economy, the CPR moved its head office from Montreal to Calgary in 1996.

Post 1994 expansion of CNR and CPR in the United States

Now fastforward again to more or less the present moment in the spring of 2021.

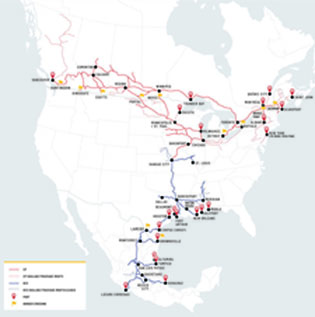

By way of quick background here, note that both the privatized CNR and the historic CPR have by this point expanded their Canadian transcontinental rail networks into the United States, by buying up smaller US operations.

The CNR in particular (aka Grand Trunk in US) has now expanded down the Mississippi Valley into New Orleans – almost poetically recalling the old French American empire in Louisiana.

The CPR (aka Soo Line Railroad) has moved at least as far south down the same Midwestern US corridor as Kansas City.

An April 2019 list of “The 5 Biggest Railroads in North America” put the CNR at number three. Another later list of “Leading North American railroads in 2019, based on operating revenue” had the CNR at number four and CPR at number six.

A May 2020 compilation of “World’s largest railway companies by market value” (rather broadly conceived it seems) put US-based Union Pacific in first place. It also reported that “Canadian National Railway [aka “CN North America’s Railroad”] came in second, valued at half of Union Pacific’s worth.”

CPR and CNR fight for Kansas City Southern in 2021

Finally, to bring things right up to date, consider two quite recent North American railroading articles – “Are We Getting Railroaded? … A train merger and the threat of monopolism on the track,” by Claire Kelloway in the admirable Washington Monthly, April 2, 2021 ; and “CN rekindles century-old rail rivalry with Kansas City Southern bid,” by Kevin Orland for Bloomberg News, April 21, 2021.

The first article tells of a current CPR proposal to buy the Kansas City Southern rail network. The big attraction of this asset is that it goes not just to the Gulf of Mexico but all the way to Mexico City, deep in the heart of the great most southerly partner in the continuing North American free-trade economic geography.

And so the second article above reports on how the CNR has now put together its own rival bid for Kansas City Southern – and its coveted connection to Mexico City. I suppose it does seem to me, as a Canadian, somewhat awkward that Canada’s two 21st century railway leaders should be publicly squabbling over such a potentially progressive big economic deal.

But in the end that just may be what the world is in 2021. I will continue to follow the issue in any case. I think it sheds interesting light on our time in Canada – and the United States and Mexico – today, as we keep struggling to bring the global pandemic to heel.

Another intriguing historical piece of the puzzle is that the French fur trader François Chouteau played a key role in the earlier 19th century founding history of Kansas City. He was a descendant of Auguste Chouteau, who was born in New Orleans in 1750 and went on to establish a fur trade outpost on the Mississippi River that ultimately grew into the city of St. Louis.

History, as noted in 1920 by a conservative young man from St. Louis who would spend most of his adult life in London, England, “has many cunning passages.”