Support for federal official bilingualism across Canada in 2024 could be a lot worse — just like it used to be

Jun 22nd, 2024 | By Randall White | Category: In BriefRANDALL WHITE, NORTH AMERICAN NOTEBOOK, TORONTO . SATURDAY, JUNE 22, 2024. When I first heard about the new Léger poll “Official bilingualism in Canada a ‘myth‘” on TV last night, I was suitably outraged.

I was 24 years old when the concept was “enshrined into law in 1969, making English and French Canada’s official languages.”

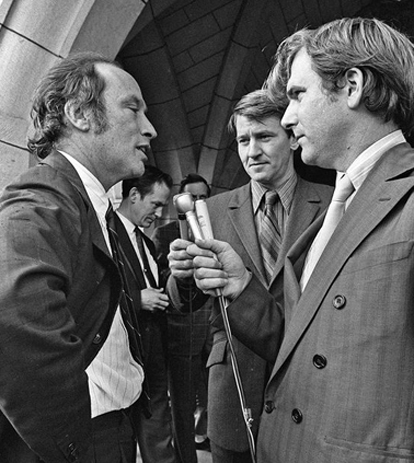

I have never been able to speak French in any serious way myself. And I did not (I thought) like, support, or vote for Pierre Trudeau when he was in office.

I was nonetheless quietly impressed with the first PM Trudeau’s 1969 implementation of an “official bilingual” policy urged by a commission which PM Lester Pearson had created in 1963 — in the midst of assorted 1960s quiet and noisy revolutions in French-speaking Quebec (culminating in the October Crisis that dominated the last quarter of 1970 in Canada).

Reading not the same as watching TV

Some 55 years later, watching TV I did find the poll reporting that “Official bilingualism in Canada a ‘myth’” discouraging and finally outrageous. Yet somewhat later, in front of my archaic PC in my old office with a window on the yard, I read the sponsoring Canadian Press report on the Léger poll. And I had a more moderate and even vaguely optimistic reaction.

Back in the late 1960s, as I recalled, no or at lest very few real-world-of-politics supporters of what became the federal official bilingualism legislation of 1969 seriously imagined that it would lead to a genuinely bilingual society across the country. The point was just that a Canadian citizen who wanted to communicate with the federal government in English or in French, in virtually any part of Canada, should be able to do so.

Practically this meant ensuring that some French-English bilingual federal public servants were stationed more or less across the country. In the end , it seems, this has largely opened up job opportunities for bilingual individuals from Quebec, outside Quebec. (Which is of course not a bad thing.) But some help also came from French immersion language classes in Canadian public schools outside Quebec, and French language training for unilingual English public servants.

Underlying this modest practical objective was of course a deeper philosophical or theoretical or even constitutional commitment to recognizing the French-speaking Canadien heritage of the modern Canadian political community . And, as some complained, it was uncertain at best just what this might eventually come to mean in the more practical longer term. (Recognizing that, as the economist J.M. Keynes liked to stress — “in the long run we’ll all be dead.”)

It’s at least much better in 2024 than it used to be

Whatever longer term thoughts were foolishly thought back then, in such Canadian places as the Toronto of the 1950s and 1960s , where I grew up, even aspiring 20-something progressive supporters of Pierre Trudeau’s 1969 bilingualism legislation never imagined that it would lead to anything remotely like a bilingual French-and-English Canadian society, coast to coast to coast.

And that was largely because the discouraging 2024 numbers in the latest Léger poll which “says … Official bilingualism in Canada a ‘myth” were just so very much worse back in the fabled 1960s, even if it was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.

In any case, something about reading as opposed to watching TV seems to induce this kind of historical perspective, at least in aging minds. And cast in this light some of the latest Léger official bilingualism numbers that the sponsoring Canadian Press report understandably enough complains about actually look pretty good.

Consider, eg, on the edge of the summer of 2024, “only 43 per cent of respondents across Canada said they held a positive view of federal bilingualism — which was enshrined into law in 1969.” Compared to what I remember from 1969, this is a vastly greater share of the Canadian people than might have confessed to any at all comparable positive view of French-English bilingualism back then — some 55 years ago.

Even more striking from this kind of historical perspective, in 2024 ONLY “Eighteen per cent of respondents held a negative view” of federal bilingualism. That number, I believe, would have been astoundingly larger in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

These two positive and negative numbers taken together do imply that just under 40% of Canadians in 2024 are somewhere in between on official bilingualism, for one reason or another. There is nothing new about that, on so many Canadian fronts. It probably is a problem in itself. We need to be stronger about making up our minds!

And then federal bilingualism is understandably more strongly supported in Quebec than in the rest of Canada. There are I certainly agree other reasons to be concerned about federal official language policy today.(And then there is the intriguing prospect that, eg, Cree, might be declared a federal official language, with different practical implications, and so forth.)

All such things considered, in conclusion it finally still does seem to me worth underlining that “43 per cent of respondents across Canada” holding a “positive view of federal bilingualism” in 2024 finally does reflect the enormous progress we have made on this still vital issue over the past half century! Things here could be A LOT worse today. And, as those of us with long memories can still remember, they certainly used to be. (O and btw with this coming Monday night in Sunrise, Florida in mind, GO OILERS! And on a final update Wed 26 Jun 24 many deep congrats to Edmonton and its hockey team for making the almost summer of 2024 interesting, all across Canada and in both official languages.)