Beware of breaking your heart with too much sadness

Oct 1st, 2009 | By Randall White | Category: Countries of the World

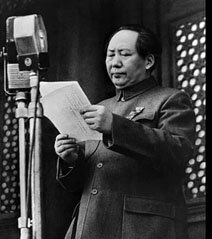

Mao Zedong declares the founding of the People's Republic of China in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, October 1, 1949.

OLD CHINATOWN, DUNDAS STREET, TORONTO. OCTOBER 1, 2009. Today is of course not the actual birthday of the late Mao Zedong (1893—1976). It is only the 60th anniversary of the official founding of the modern People’s Republic – when Mao made the now historic declaration: “China has stood up!”

The new Chinese role in the world economy, on display at the recent G20 summit in Pittsburgh, is one hard example of where this standing up has led, in a mere two generations. But it is no doubt not easy to imagine what Mao would make of what has happened since his death in 1976.

In the blockbuster movie that the People’s Republic itself has made to celebrate its 60th anniversary, “the actor playing Mao Zedong holds back tears and emotionally proclaims” the official founding in 1949. But the “film then awkwardly hurries forward to December 1978, when Deng Xiaoping heralds the era of ‘opening and reform’ in the Middle Kingdom” – leading to the strange yet in at least some ways impressive blend of Chinese culture, communist state, and capitalist economy in China today.

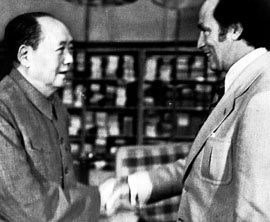

Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau meets Mao Zedong, China's ultimate leader, in October 1973 during China's historic opening to the West.

It was also Deng Xiaoping who declared in 1981 that Chairman Mao was still “70 per cent right” and only “30 per cent wrong” – and clearly, in effect, still the founding father of the modern People’s Republic of China. (More or less, it almost seems fair enough to say, as the quasi-colonial-aristocrat George Washington is still the founding father of the modern free and democratic republic of the USA?)

In the more recent past books like Li Zhisui’s The Private Life of Chairman Mao (1994) and Jung Chang and Jon Halliday’s Mao: The Unknown Story (2005) have reported on “the crumbling of the Mao myth” – and shown how the Chinese themselves “are getting rid of their Mao myth,” as they continue their new long march to the status of the world’s new largest national economy (which does seem almost unstoppable, right now at any rate).

Yet if Mao Zedong in real life was nothing like the socialist saint some still tried to imagine in the 1960s – and if the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were disastrous policies at best – Mao also “united fractured, war-torn China, restoring its pride and self-confidence after two centuries of humiliation.” (Eric Margolis). He was a dictator and a ruthless, Machiavellian political leader, and no democrat at all. But “the dictator said many beautiful and idealistic things” (Andrew Nathan), which he does seem to have more or less believed, in spite of his cynicism and harsh political realism, steeped in a long and ancient literature of hyper-worldly Chinese statecraft.

Chang and Halliday’s Mao: The Unknown Story urges that the modern Chinese founding father was no better than those other two commanding dictatorial political leaders of the 20th century, Hitler and Stalin. But unlike the states that they founded, the state Mao Zedong founded is still very much in business – even if not quite the same business that Mao intended, or hoped for.

Moreover, among his many other triumphs and tragedies, Mao Zedong was a poet of no small accomplishment. And even just in English translation I find it impossible to read his poems, and recognize quite the kind of inhuman monster that Chang and Halliday have tried to promote (“lazy, uncommitted, driven by lust for power and comfort, lacking in original ideas, tactically smart but strategically stupid, disliked by everyone he works with, selfish and mindlessly cruel”).

There is no point in destroying one set of myths, only to replace them with another. The history that is useful is more than this. So happy 60th anniversary to the Chairman Mao who wrote “To Liu Ya-tzu” in April 1949 (less than half a year before Mao stood in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, and declared the official establishment of the People’s Republic of China) :

“I can never forget the tea we took in Canton / And the poem you asked for in Chungking / as the leaves were turning yellow. / Thirty-one years have passed / and I am back in this ancient capital ; / at the season of falling flowers / I am reading your beautiful verses. / Beware of breaking your heart with too much sadness ; / Always take a farsighted view of world events. / Do not say that the waters of Lake K’unming are too shallow ; / For watching fish they are better than Fuch’un River.”

[This poem is taken from the collection “Thirty-seven Poems by Mao Tse-tung,” translated from the Chinese by Michael Bullock and Jerome Ch ên, in Jerome Ch ên, Mao and the Chinese Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965, 1967.]