Gilles Duceppe’s a nice guy – but really out to lunch on what real Quebec independence would mean

Oct 15th, 2010 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

From Canadian satirical blog, “the Hammer,” on “Election 2004: Let the bloodbath begin ... The Bloc likes its chances in Calgary. ‘People in Alberta wanna separate, we wanna separate. Sounds like a match made in heaven,’ said Bloc Leader Gilles Duceppe.”

If you search “Gilles Duceppe” in the online editions of either the Washington Post or the New York Times at the moment, you will just get “No Results Found” or “Your search – Gilles Duceppe – did not match any documents under Past 30 Days.”

Even if you try the same game on Le Devoir.com, all you will get is a Wednesday, October 13 article that explains how “Le chef du Bloc québécois, Gilles Duceppe, ira à Washington demain et vendredi pour promouvoir l’idée de la souveraineté québécoise.”

It takes the Globe and Mail in Toronto – “Posted on Friday, October 15, 2010 9:55AM EDT” – to report plainly how, in a talk to “the Woodrow Wilson Centre and Hudson Institute as part of a two-day visit to Washington,” M. Duceppe has boldly declared: “I am here to tell you that the question of Quebec’s political future is by no means settled … A sovereign Quebec will be a win-win outcome for Quebeckers, Canada, the United States and the world – for everyone except those who are nostalgic for a Canadian dream that no longer exists in reality.”

Well yes, of course. That is still what the leader of the Quebec sovereigntist party in Canadian federal politics pretends or perhaps is bound to think. But those of us in the rest of the country may be excused if we take the same opportunity to tell Gilles Duceppe, however much we may otherwise like and even admire him (and his contribution to Canada today, from coast to coast to coast) that he is dreaming in technicolour, at the very least.

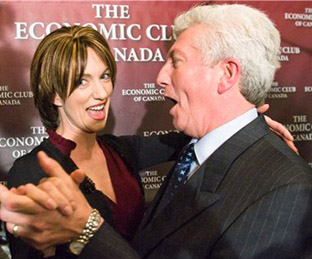

CBC comedienne Geri Hall dances with Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe after interrupting a news conference in Toronto, October 3, 2008. REUTERS/Mark Blinch.

An altogether independent Quebec that actually did separate altogether from Canada would be nothing like a win-win outcome for Canada, or for Quebeckers. (Although it might finally prove quite agreeable to the United States.)

Just to start with, it is now quite clear from much meditation since the 1960s that Quebec as an altogether independent sovereign country in its own right would just destroy Canada as we know it today – geographically and in every other way imaginable. The first resolutely enraged impulse of the rest of the country would be to make sure that the new Quebec had a much less favourable position in what remained of the northern North American economic space than it enjoys today – in the age of the Quebecois as a nation within a united Canada.

Would Quebec really be better off if the rest of the country joined the USA?

The second impulse of the anglophone-majority rest of Canada, after its rage had a chance to cool off, would more than likely enough be to join the North American anglophone majority in the United States, at long last. Not happily or with any enthusiasm, but just as a kind of distressing but logical last resort.

Gilles Duceppe, Bloc Quebecois MP, left, for Laurier-Ste-Marie is congratulated by, left to right, Andre Boulerice, Lucien Bouchard, and Gilles Rocheleau, after swearing his allegiance to Quebec in a ceremony in Hull, Quebec, on Sunday September 23, 1990. Photo: The Canadian Press.

Really, after all: what would be the point of keeping together a country with a big geographical hole in the middle – with the four Atlantic provinces cut off from the regions west of the Ottawa River (vaguely resembling the old East Pakistan that finally became the independent Bangladesh), and with the single province of Ontario taking up somewhat more than 50% of the population in the remaining nine provinces and three territories all together?

And if you are wild and crazy enough to think an 8-million francophone-majority Quebec would actually be better off on a continent that includes just one 345-million anglophone-majority United States of North America, try riding the train from Montreal to Miami, in the dead of the Canadian winter.

(Where you can carefully observe just how most citizens of the USA today feel about spending a lot of time in confined spaces with people speaking French!)

The first people who called themselves Canadians are still more Canadian than anyone else!

The ultimate barrier to an altogether independent Quebec, completely separate from Canada, almost certainly lies not in the rest of the country, but in Quebec itself. This is a hard truth that the Quebec sovereigntist movement has never been able to face up to squarely (for understandable enough reasons, no doubt).

You can see this truth in the results of the two Quebec sovereignty referendums to date – neither of which actually proposed an altogether independent Quebec. You could see it in the intermittent confused pronouncements of eminent allegedly sovereigntist Quebeckers during both past referendum debates. You can see it as well (even if this plain empirical fact is seldom commented on, inside or outside Quebec) in current Statistics Canada data on ethnic origins.

In Quebec in the last census of 2006, eg, an estimated 3,213,525 people reported so-called single “Canadian” ethnic origins (compared, btw, with a mere 94,890 people who reported single “Québécois” origins). In the rest of Canada ( with a population some three-and-a-half times larger than Quebec’s) a mere 2,535,195 people reported so-called single “Canadian” ethnic origins. Put another way, even in the early 21st century more people in Quebec report Canadian ethnic origins than in any other province of Canada.

Bloc Quebecois leader Gilles Duceppe and his wife, Yolande, look for their poling station as they arrive to vote in his riding in Montreal, Que., Tuesday, Oct.14, 2008 as Canadians vote in a general election. (Photo by Jacques Boissinot/CP).

This at least shouldn’t be at all that difficult to understand. “Canada” is a North American aboriginal word. And as the near-great Canadian historian Harold Innis explained long ago, “the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.” In the modern history of Canada that starts in the 16th and 17th centuries, however, the ancestors of the francophone majority in Quebec today were the first people to call themselves Canadians.

Being Canadian – or Canadien – is still a crucial part of the identity of many Quebeckers (and especially including francophone Quebeckers). In the 2006 census when you add the 1,260,595 Quebeckers who included “Canadian” among their “multiple” ethnic origin responses to the 3,213,525 Quebeckers who gave their “single” ethnic origin response as Canadian you have accounted for more than 60% of the province’s total population.

(A similar calculation with people giving both single and multiple ethnic origin responses as “Québécois” – as in Parti or Bloc Québécois, to take the obvious political cases in point – accounts for less than 2% of the total population.)

There are no doubt a variety of appropriate qualifications to these statistics. Exactly what they mean politically raises assorted subtle questions. It is certainly true that nowadays M. Duceppe’s Bloc Quebecois is the most popular federal party in Quebec – with more than 38% saying they would vote BQ in the next federal election, in the latest EKOS poll.

Yet, however you look at it all, the plain enough fact remains that there is nothing like a democratic majority inside Quebec for an altogether independent new country, completely separate from the Canada in which the identity of so many Quebeckers is still bound up.

Over the past several decades there have been points at which something close to a popular majority has emerged for some kind of aggressively negotiated new deal for Quebec inside Canada – “sovereignty association” or some new form of “economic union,” and so forth.

But much has changed in both Canada and Quebec since the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s – through the hard work of a half-century of inspired francophone political leadership. Whatever else may or may not qualify as the deepest truth, les Canadiens in the St. Lawrence valley have become masters in their own house, at last, in the long journey from 1759 to the present.

As a result (and as M. Duceppe’s recent talk in Washington itself almost seems to imply, between the lines), the Quebec that remains in a united Canada already has something much closer to some sovereignty-association new deal than any altogether independent new country, completely separate from Canada (and its ultimate destroyer)Â could ever hope to enjoy.

If Gilles Duceppe really does not know this, he’s nowhere near as smart as he sometimes looks.

” the Quebec that remains in a united Canada already has something much closer to some sovereignty-association new deal than any altogether independent new country”.

Indeed. BUT, would Quebec have the rights and relative independence it enjoys today without the nationalist movement? Without the two referenda? Without the threat of separation? I doubt it. The nationalists failed in their ultimate goal but succeeded in getting Anglo Canada to accept what previous generations refused. It is people like Levesque and Duceppe that gave Quebec made what Quebec is today, not the narrow-minded conservatives of the Quebec Liberal Party.