Why Kelly McParland is wrong about the British monarchy in Canada

Dec 31st, 2010 | By Randall White | Category: Canadian Republic

Pamela Anderson hosts a party in Montreal as part of the 2007 Grand Prix festivities. Photograph by: Tim Snow, Gazette File Photo.

I am not a fan of the National Post. But over the 2010 holiday season I think it deserves some credit for contributing to both sides of what is not quite yet an important debate we will be having in Canada, if and when we show serious signs of surviving the 21st century.

To kick things off, on December 22 Lorne Gunter posted an article called “It’s time for Canada to break ties with the British.” This title was a bit misleading. What Gunter argued was that before the current Prince of Wales falls heir to the throne, “it would be smart of us to debate a made-in-Canada alternative” to the British monarch as our ultimate symbolic head of state. And this is not quite the same as breaking “ties with the British.”

That was one side of the debate (with which I broadly agree). For the other side, on December 25 itself Kelly McParland posted an article arguing against Lorne Gunter’s thesis, called “The choice between King Charles and President Harper.” (This title was also misleading – for reasons I will discuss below.)

To help carry on the debate, in a very modest and respectful way, I want to take up each of the six numbered arguments Kelly McParland makes, and show why I think they just do not add up in the year 2010 – to say nothing of 2011 and beyond :

(1) What would be achieved? McParland begins by declaring that severing our remaining (and now entirely symbolic) ties with the British monarchy in Canada “would achieve nothing” for “the lives of any Canadians, other, perhaps, than the Governor General and a handful of politicians and officials in Ottawa.”

Elizabeth II signs the Constitution Act 1982, with its Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, while Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau looks on.

This seems to me quite wrong, in at least two different senses. First, if the broad impact of severing ties with the British monarchy in Canada is so minimal, why do such people as Kelly McParland object to it so strenuously? The plain enough answer, it seems to me, is that it would in fact achieve things – but not things that McParland and others sharing his views would like.

Second (and to just touch on some of the specific things that would be achieved), to wave goodbye to the British monarchy in Canada (politely of course) would and I believe finally will be the crucial last step in a long quiet evolution away from what the late René Lévesque used to aptly disparage as “the colonized mind,” in many different walks of Canadian life.

This evolution goes back at least as far as the modern Canadian democratic patriotism that crystallized during the First World War. It includes: the so-called Statute of Westminster of 1931, “clarifying the powers of Canada’s Parliament and those of the other Dominions, and granting the former colonies full legal freedom”; the first Canadian Citizenship Act of 1947, which created for the first time the status of a Canadian citizen, as opposed to a British subject resident in Canada; the adoption of an independent Canadian flag in 1965, to replace the old British red ensign in Canada (an act adamantly opposed by those I think it is not too unfair to call Kelly McParland’s spiritual ancestors); and the Constitution Act 1982, which gave we the Canadian people our own Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and created an independent formula by which Canada can amend its constitution without recourse to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, legal creator of our original Constitution Act 1867 (formerly known as the British North America Act).

To make a long story very short, I think that taking the last crucial decolonizing step in this long quiet evolution, away from the British monarchy, will give a vital shot in the arm to many different aspects of Canadian public life, and the ordinary lives of many individual Canadians. And this will better enable us to manage the tough new challenges of the 21st century.

(And if you do not think we need this kind of shot in the arm, it seems to me at any rate, you are probably not paying enough more or less serious attention to what is going on in the fast lanes of Marshall McLuhan’s global village today.)

(2) Canada’s real British heritage of parliamentary democracy. By turning our backs on the British monarchy in Canada, Kelly McParland claims: “We’d have broken a link that is an essential element of our history. It’s never a good idea to throw away history, and this is still a young country; we’re still making most of our history, and we don’t have a surfeit we can afford to waste.”

First volume of the much-praised Historical Atlas of Canada, 1987: “the pattern of Canada has been taking shape for almost 500 years, and by New World standards is old.”

To start with here, we are not in fact such a young country. As R. Cole Harris at the University of British Columbia wrote in his preface to the justly much admired late 1980s first volume of the Historical Atlas of Canada: “the volume has tended to confirm Harold Innis’s general insights … As Innis maintained, the pattern of Canada has been taking shape for almost 500 years, and by New World standards is old.”

Viewed from the perspective of the early 21st century, the British monarchy as such is not all that important an element in our 500-year history that by New World standards is old. In much of the country as we know it today the British monarchy was a Johnny-come-lately to the multiracial (and multicultural) “French and Indian” fur trade. “Canada” itself is an aboriginal word. And as the near-great Canadian economic historian Harold Innis also told us as long ago as 1930: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.” The first people who called themselves “Canadians” were the French-speaking residents of present-day Quebec – who, as countless opinion polls continue to make clear, have seldom been great fans of the British monarchy in Canada.

Moreover, there is indeed something “British” that remains “an essential element of our history,” and has endured in important practical ways down to the present. But it is not the British monarchy. It is the British or “Westminster” model of parliamentary democracy. This was ushered onto the local political stage in the middle of the 19th century, in response to assorted local agitations and protests, by the “Right Honourable James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin, 12th Earl of Kincardine and Governor General of British North America (1847-1854).”

It is not exactly an accident that there is today in the Canadian capital city of Ottawa (another aboriginal word) a Lord Elgin Hotel. (There is, on the other hand, still a Queen Victoria Hotel in Canada, but it is in Victoria, BC, the provincial capital of British Columbia.) It is similarly our British-style parliamentary democracy, and not the British monarchy, which distinguishes our modern Canadian political culture from that of the United States.

As various recent debates have suggested (think “coalition” and “prorogation,” eg), we increasingly do not understand how our British-style parliamentary democracy is meant to work as well as we used to. And that, I think, has something to do with the tendency of too many among us to see the current focus of our residual British heritage as the British monarchy – which no longer has anything practical to do with our political life.

(3) A made-in-Canada alternative is not all that difficult. Kelly McParland writes: “In the absence of a head of state, we’d have to come up with an alternative. Who would that be… the prime minister? The Governor General? A newly established position, such as the President of Canada? All of these have major problems: I can already hear the screeching from the Liberal/socialist/separatist coalition should Stephen Harper dare to put himself forward as Canada’s new head of state. That being the case, the GG would be the logical alternative, except, based on recent history, it would mean putting the ultimate fate of the country into the hands of academics, CBC hosts or former politicians. Peter Mansbridge, ruler of all he surveys? I don’t think so. Ditto for creating a new position; ‘President of Canada’ is far too American-style to get past the first round of town halls that would inevitably be required to weigh public opinion.”

All this just makes clear that McParland has not investigated the subject in any depth. Other former British dominions have already successfully made the transition from Westminister parliamentary democracy with the British monarch as ceremonial head of state, to Westminister parliamentary democracy with an independent (or republican) ceremonial head of state. And they have not had any “major problems.”

EXPERIENCE IN OTHER FORMER BRITISH DOMINIONS. As a practical matter, the notion that minority prime minister Stephen Harper would “dare to put himself forward as Canada’s new head of state” is a canard at best. There is some vague precedent for this kind of option in the experience of the former British dominion of South Africa since 1984. But this is an unusual model, with little influence elsewhere. In the real world it is not a question of “King Charles or President Harper.” And the answer in this reductio ad absurdum case is just none of the above.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, New Delhi, 4 August 1947, negotiating the final touches on the independent British dominion of India, which became the first parliamentary democratic republic in a new kind of Commonwealth of Nations in 1950.

The experience of the former British dominions of Ireland and India offers more constructive food for thought. In both these cases a reformed office of the governor general (already often said to be our de facto head of state in Canada) was promoted from the British monarch’s local representative to essentially ceremonial head of state in his or her own right. The crucial reform on these models is to broaden the selection method for the office. The new independent head of state, that is to say, is not chosen by the partisan prime minister of the day, as the governor general is now in Canada (or Australia, Jamaica, New Zealand, and other so-called present-day “commonwealth realms”). In India the independent republican head of state is indirectly elected by the federal and state legislatures. In Ireland the head of state is directly elected by the Irish people, from among candidates nominated by the national legislature.

A MADE-IN-CANADA ALTERNATIVE. I do think that a replacement for the British monarch as head of state that will work in our particular Canadian circumstances will finally have to be something like what Lorne Gunter has called a “made-in-Canada alternative.” Some monarchist critics, when confronted by the practical potential of the Irish and Indian reform models, complain that these precedents go against some Canadian grain. They urge that Ireland is at the moment in considerable financial difficulty, and that even modern democratic India is a much, much different country from Canada. Both these urgings are of course true enough. But they have nothing at all to do with the proven success of the Indian and Irish methods of selecting an essentially ceremonial head of state in a Westminster or British-style parliamentary democracy.

Canot de maître shooting the Rapids/Rabaska descendant un rapide, Frances Anne Hopkins,1879. It was the multiracial and multicultural fur trade, not the British monarchy, that first took Canada from coast to coast to coast.

At the same time, like at least a few others who have pondered the subject a bit, I think we in Canada will be best served by some blending of the Indian and Irish models. The failed Australian republican referendum of 1999 suggests that the Irish method of directly electing the ceremonial head of state in a parliamentary democracy will have the most popular appeal in the 21st century. The Irish model itself (which has worked very well since the late 1930s) also suggests that the nomination process for this direct election is important in keeping the office an essentially ceremonial one. And in our Canadian federal system, with both strong provinces and (in theory at any rate) a strong federal government, a nomination process that gave a role to both federal and provincial legislatures, on the Indian model, would make a lot of sense.

The process for selecting our independent Canadian head of state would also have to take some formal account of our two official languages – and perhaps a few other features of our unique northern geography. There are some far from impossible questions too about how a reformed office of governor general as federal head of state would relate to what are now the provincial lieutenant governors (especially perhaps in Quebec?).

Finally, I am not sure I agree with Kelly McParland’s argument that “‘President of Canada’ is far too American-style to get past the first round of town halls that would inevitably be required to weigh public opinion.” (In the real world of Canada today I think it is almost equally plausible that the opposite could be true, but who can say with any serious confidence in advance?) I would not object myself to just keeping the term “Governor General” for the independent ceremonial head of state of our continuing Canadian parliamentary democracy – although I know that some and perhaps even many Canadian republican activists today do not like this option at all. There are other names or formal titles as well, of course. An ultimate popular referendum on the larger issue might include a few options for the name of the new office.

(4) Yes We Canada! “Canada,” Kelly McParland not so boldly declares “is a country incapable of discussing serious issues, much less settling them. It is forbidden to mention abortion, alternative methods of financing health care, or anything that might annoy Quebec. We hand anything difficult to judges to avoid dealing with it ourselves. So the odds on Canadians ever agreeing on an alternative to the monarchy are too long to calculate. We have a better chance of all winning the lottery on the same day than we do of settling that one.”

Canada’s near-great economic historian Harold Innis (1894—1952), raised on a family farm in southwestern Ontario, wounded in the First World War, first Canadian-born chairman of the political economy department at the University of Toronto (earlier holders of this post were from the United Kingdom), and first Canadian-born president of the American Economic Association.

Who can deny that there is a certain dysfunctional realism in assertions of this sort? What I quite strongly believe myself, however, is that this is just a counsel of weakness. And if we continue to take such counsels to heart, the prospects that Canada will survive the 21st century, or even the next several decades, seem to me quite dim.

History, T.S. Eliot, said back in the early 20th century, “has many cunning passages.” Moving beyond the British monarch as our ultimate Canadian head of state is just what we need to energize and steel ourselves for the tough challenges of the 21st century that lie ahead. A rigid old colonial Canadian elite culture that insists on preserving the increasingly palpably obsolete British monarchy at the apex of what is supposed to be our modern “free and democratic” political system will just set the stage for the ultimate annexation of the Canadian provinces by some resurgent new United States of North America in the 2020s or 2030s and/or beyond.

That is not of course what an earlier generation of Canadians believed. But it is, I think, the increasingly plain truth today. There is an emerging Canadian people in the year 2010, as best as I can make out, that wants to be the sovereign in its own democracy – or what our Constitution Act 1982 already does call a “free and democratic society.” If Canada itself is not prepared to become this kind of democracy, the alternative democracy next door will become increasingly more attractive. To believe that yes Canada today can finally move beyond its 19th century colonial attachments to the British monarchy successfully is just to believe in the future of Canada and the Canadian people, in all their inspiring diversity, from coast to coast to coast.

(5) The decline of British ethnicity in Canadian society. McParland writes: “The British monarchy is a line stretching back nine and a half centuries, with one brief interruption. There have been plenty of unimpressive sovereigns in that time, but none that caused enough damage that it couldn’t be readily repaired. The suggestion that Prince Charles is so unpromising that the whole line should be abandoned, as Lorne suggests, seems more than a little out of proportion. For one thing, we have no idea what kind of king he’ll actually make. He may be a “New Age flake,” but his grandfather George VI wasn’t looked on with much excitement either, and now they extol him as a courageous man who overcame personal handicaps and an enormous dread of the job to lead his country through some of its darkest years. Besides, batty ideas about architecture and farming methods are hardly fatal to a country that could use the diversion.”

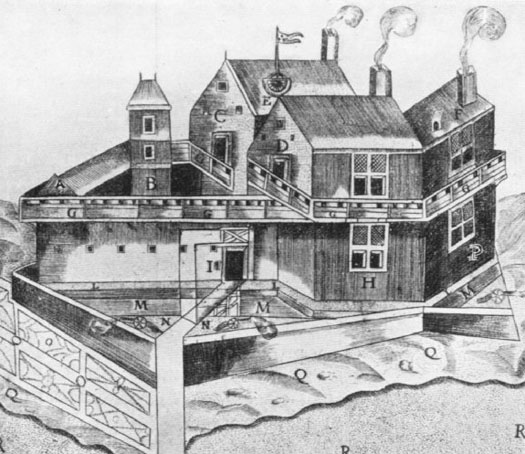

Samuel de Champlain’s drawing of the original “Habitation” at Quebec City. He had a “vision ... of the production , here in North America, of a new race, stronger for the mingling ... of many and varied strains.” E.C. Drury, Premier of Ontario, 1919—1923.

The unmistakable problem with this kind of talk in Canada today, it seems quite clear to me, is that it can only logically appeal to people who see themselves as in some degree directly attached to one or another form of “British” ethnic ancestry, heritage, or origin. Otherwise, you can say similar things about, eg, the Emperor of Japan or the Pope of the Roman Catholic Church. And presumably Kelly McParland and others who share his views would not seriously suggest that Canada today should embrace either of these august figures as ceremonial head of state (even if the figures themselves were to agree).

Even in the later 19th century people of British ethnic heritage did not make up any overwhelming majority of the Canadian population at large. According to Statistics Canada, people with “British origins” accounted for only 60.5% of the Canadian population in 1871. The proportion had dropped to 55.4% in 1921, 47.9% in 1951, and 44.6% in 1971. Since then data on ethnic origins has been classified in somewhat different ways, that make direct comparisons difficult. But in the most recent 2006 Census only 35.5% of all “single and multiple ethnic origin” responses combined for Canada at large were accounted for by “British Isles origins.” And “British Isles origins” accounted for only 15.3% of all so-called “single origin” responses.

Neelam Verma, born in Montreal and raised in Toronto, by parents who had migrated from India. Winner of Miss Universe Canada 2002. Graduate of York University's Schulich School of Business. Anchor for Bollywood Boulevard on Rogers TV. Host of Canoe Live on Sun TV, a show on “Canadian news, entertainment, culture and lifestyle.”

It is true enough that other places where people with British ethnic origins do not account for a majority of the population are still so-called “Commonwealth realms,” that recognize the British monarch as symbolic head of state. The clearest examples include Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu. Republican movements and even government plans for republican destinies are already afoot in a number of these places, however, and it is doubtful that many of them will remain Commonwealth realms into any distant future. (And note here too, btw, that the majority, or 33, of the Commonwealth’s current 54 independent member states are republics nowadays.)

It is also true enough that English remains the language of the majority of the diverse modern Canadian people in all Canadian provinces except Quebec (and, to a lesser extent, among the strong French-speaking Acadian minority in New Brunswick – and in the new Nunavut territory in the Arctic far north). Yet English is at least one of an important, majority, official, or predominant language in 56 other countries in the world today – a quite decisive majority of which (41) do not recognize the British monarch as symbolic head of state. (Key large examples of course include Canada’s friendly giant neighbour the United States of America, along with India, Pakistan, Nigeria, South Africa, and the Philippines.)

On a final note here, along with the increasing number of Canadians who are not comfortable with the British monarchy because it ultimately seems to (and in effect almost certainly does, in some degree) assign higher status in Canadian public life to people with one or another form of “British” ethnic ancestry, heritage, or origin, there are increasing numbers of Canadians who do not like Kelly McParland’s “line stretching back nine and a half centuries,” because it is based on principles of hereditary authority that violate any reasonable understanding of the modern democratic ethos – and even help sustain certain residual elitist or quasi-aristocratic elements in Canadian public culture. (And I must confess that I am one of these Canadians myself.)

(6) Kudos to Kelly McParland for his sense of humour! Kelly McParland concluded his Canadian pro-monarchy meditations of December 25, 2010 with: “In a world obsessed with the trivial (one television station chose Christmas Day to broadcast a lengthy profile of the Kardashian family, who are apparently famous for something), the Royals offer a pleasant diversion from more serious problems. Canada’s tenuous link lets us laugh at them with a certain insider status. Laughs are hard enough to come by in today’s world, and the monarchy has been a reliable supplier. Prince William isn’t even King yet and already he seems set to keep up the tradition, if the recently-released coin of the Prince and Kate Middleton is any measure. Looks more like Elvis and Janis Joplin. You can’t buy humour like that.”

Kardashian family Christmas card photo, 2010. It lacks the historical depth of the British Royal family, but ...

I must concede that the generations of British “Royals” who follow Queen Elizabeth II (a lady still much if far from universally respected in Canada, I also agree) frequently do strike me as something of a joke, on various levels. It similarly seems to me that one of the current problems of the British Royal family is that it has increasingly become just another branch of the evanescent celebrity culture in the contemporary English-speaking global village. It has a history that such Los Angeles peers as the Kardashian family certainly cannot touch. And yet… it may just be me, but if I have to watch one or the other on TV, for no more than five minutes at any rate, I think I just might choose the Kardashian family. (At least one of the daughters has close to intoxicating raw sex appeal – I think in any case, as best I can remember from the last time I stumbled across them channel surfing.)

From one angle, the joke of the British monarchy in Canada is just another of its problems. Or, like more and more Canadians, I am someone who would agree that the monarchy in Canada is no longer of any real importance or significance in Canadian public life. And you might say, in that case why bother with its future? Let sleeping dogs lie, etc, etc. But you might also reasonably ask: what kind of country continues to have something of no real importance that nowadays just promotes humour at best, as its legal or official or constitutional “head of state”?

From another angle, I want to end these excessively long-winded reflections by commending Kelly McParland for ending his archaic pro-monarchy-in-Canada rant on a humourous note. If we are finally going to act on Lorne Gunter’s good advice that before the current Prince of Wales falls heir to the throne, “it would be smart of us to debate a made-in-Canada alternative” to the British monarchy (as I certainly hope we will, and soon enough), it is going to be very important to preserve some degree of civility. My own experience as an emerging Canadian republican over the past several years, discussing the future of the monarchy in Canada with various friends and foes, is that the issue can all too often generate heated and hostile emotions. (And on everyone’s part, including my own, I must unhappily report – and even though almost everyone agrees that the issue is just not all that important, practically.)

“We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.” Harold Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada, 1930. Painting by John Buxton.

Humour is, I think, the best possible antidote to all this. In a geographically very large but still demographically modest country like Canada today, which cannot realistically have any vast international pretensions, it ought to be possible to debate the most fundamental question of just where the ultimate source of political power and governmental authority lies with something that at least approaches good humour.

And on a very final note I would just urge on Mr. McParland what, on the basis of more than six decades of direct observation now, strikes me as, at the very least, a very real possibility. And this is that the modern sovereign Canadian people, in all their near-miraculous diversity, coast to coast to coast – and including the Québécois who constitute a nation within a united Canada (to say nothing of the Assembly of First Nations, liberated women, straight or otherwise born-in-Canada Canadians, assorted children of the old global empire or empires, on which etc, etc, etc) – will finally prove to be an even better source of the kind of humour you just can’t buy than either the Kardashians, or the British Royal family.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Raymond. Raymond said: Why Kelly McParland is wrong about the British monarchy in Canada – Counterweights: http://bit.ly/dRFIO0 via @addthis […]

http://topsy.com/www.counterweights.ca/2010/12/why-kelly-mcparland-is-wrong-about-the-british-monarchy-in-canada/?utm_source=pingback&utm_campaign=L2

Randall…a great read and almost 100% concurence on your arguments ( The only issue is that I’m not too fond of retaining the GG appelation under a republican arragement). Damn it…I would have liked to have read your article in the National Post. You do have a way with words and it is most enjoyable to read your arragement of them.

All the best in 2011.